RECIPES

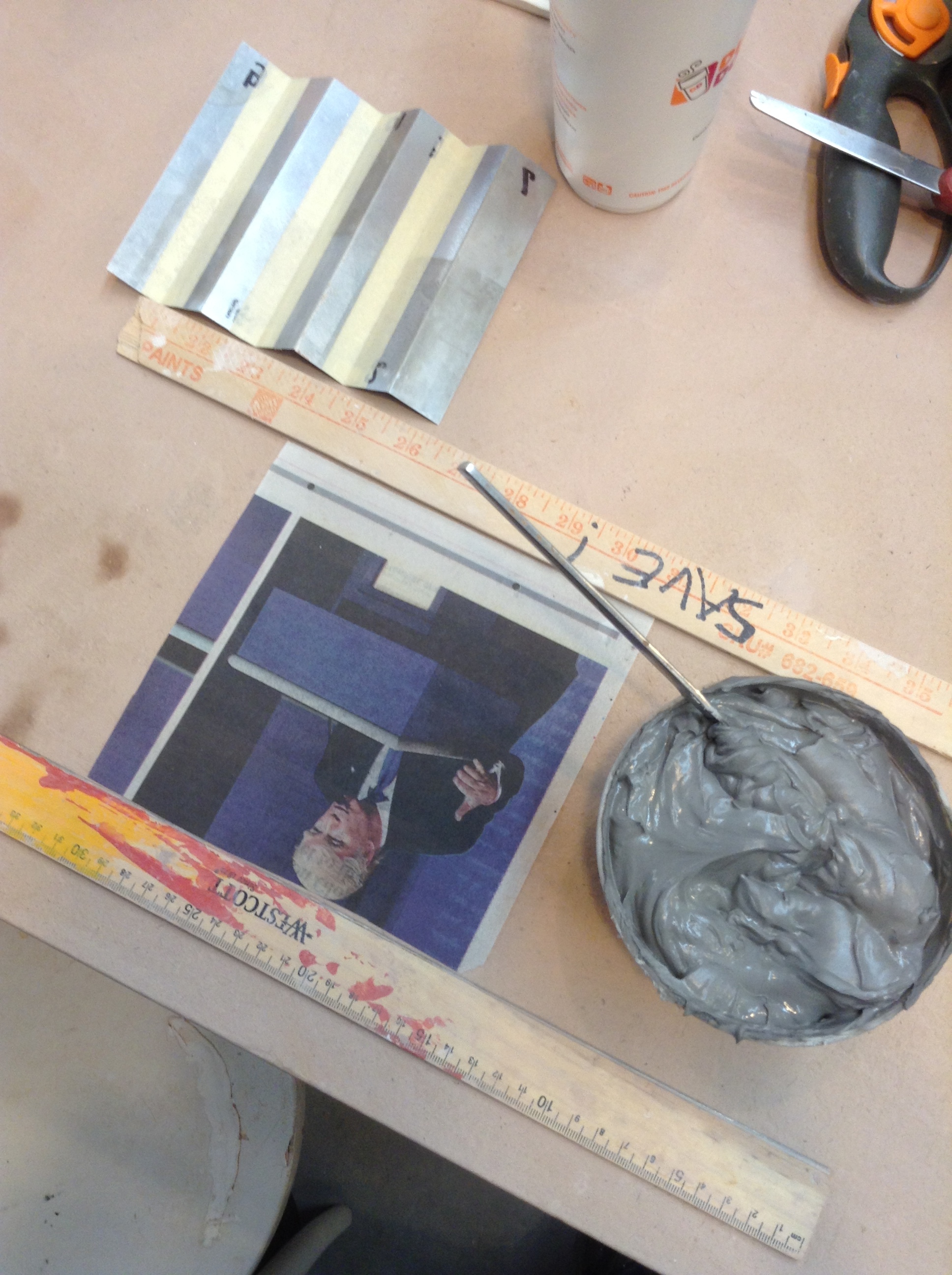

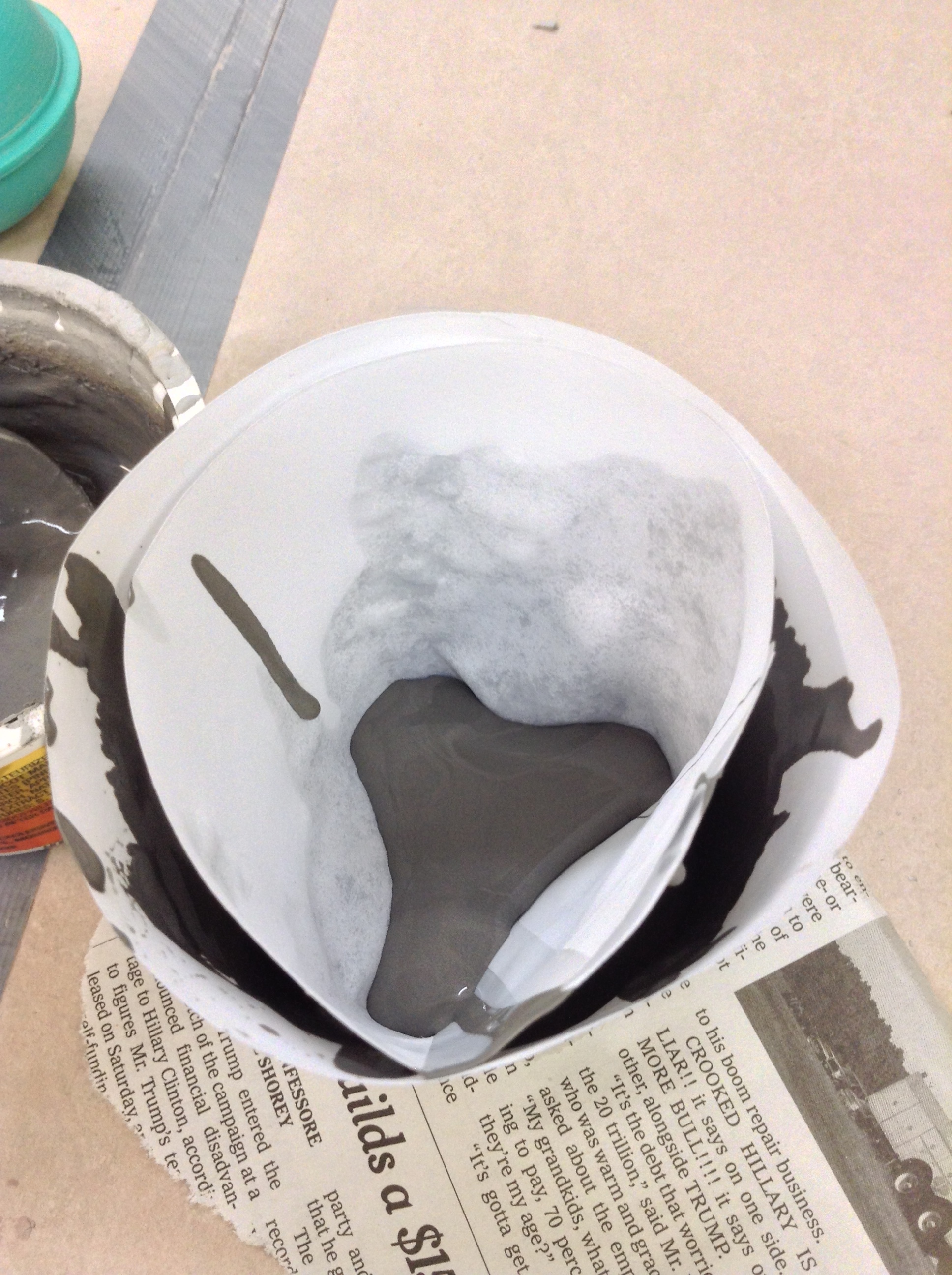

- Paste or Frosting-like clay slip: About two tablespoons per cup of slip, stirred really well. Add a little more for thicker paste, add a little water for thinner slip. Adding unaltered clay slip seemed to affect it less than adding plain water did.

- For slip trailing (that will still comfortably pass through a squeeze bottle tip): a few drops of vinegar per cup of slip. Be careful adding vinegar in minute amounts. A consistency you can still squeeze through the bottle gets inconveniently thick very easily.

Should you, or could you, make these slips from your existing moist throwing body? You can, but it's an amount of work people cringe at the thought of doing. If you need the moist clay and slip clay to match, then you must do it. It will be a bit less work if you start from your mushy recycled bucket because it's already fairly wet. The difference is only slight between the recipe for the familiar moist clay from bags, and a clay slip that can be fluid enough to squeeze through nozzles. Many good explainer articles provide varying levels of detail on how to mix up soft clay pastes like these from different starting points.

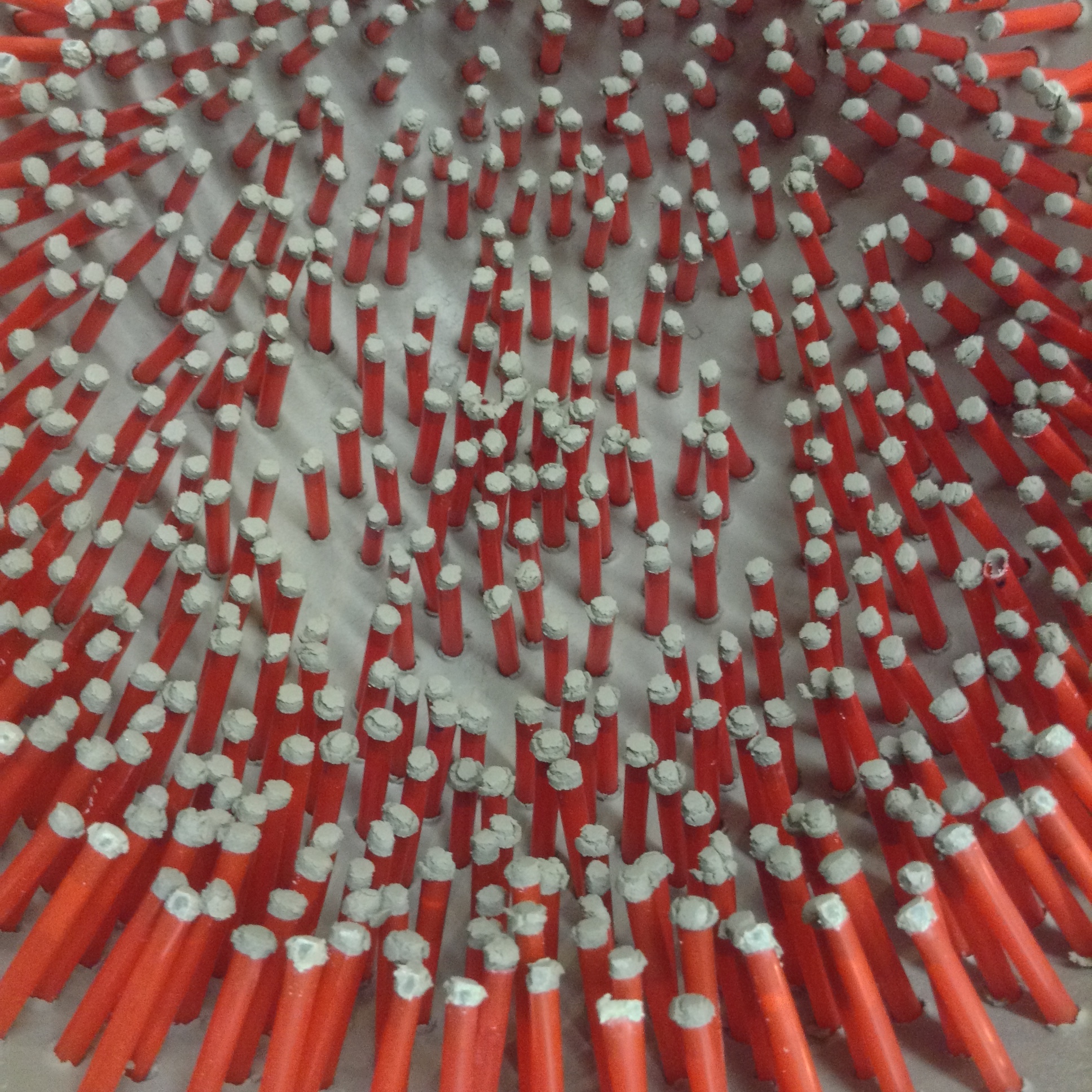

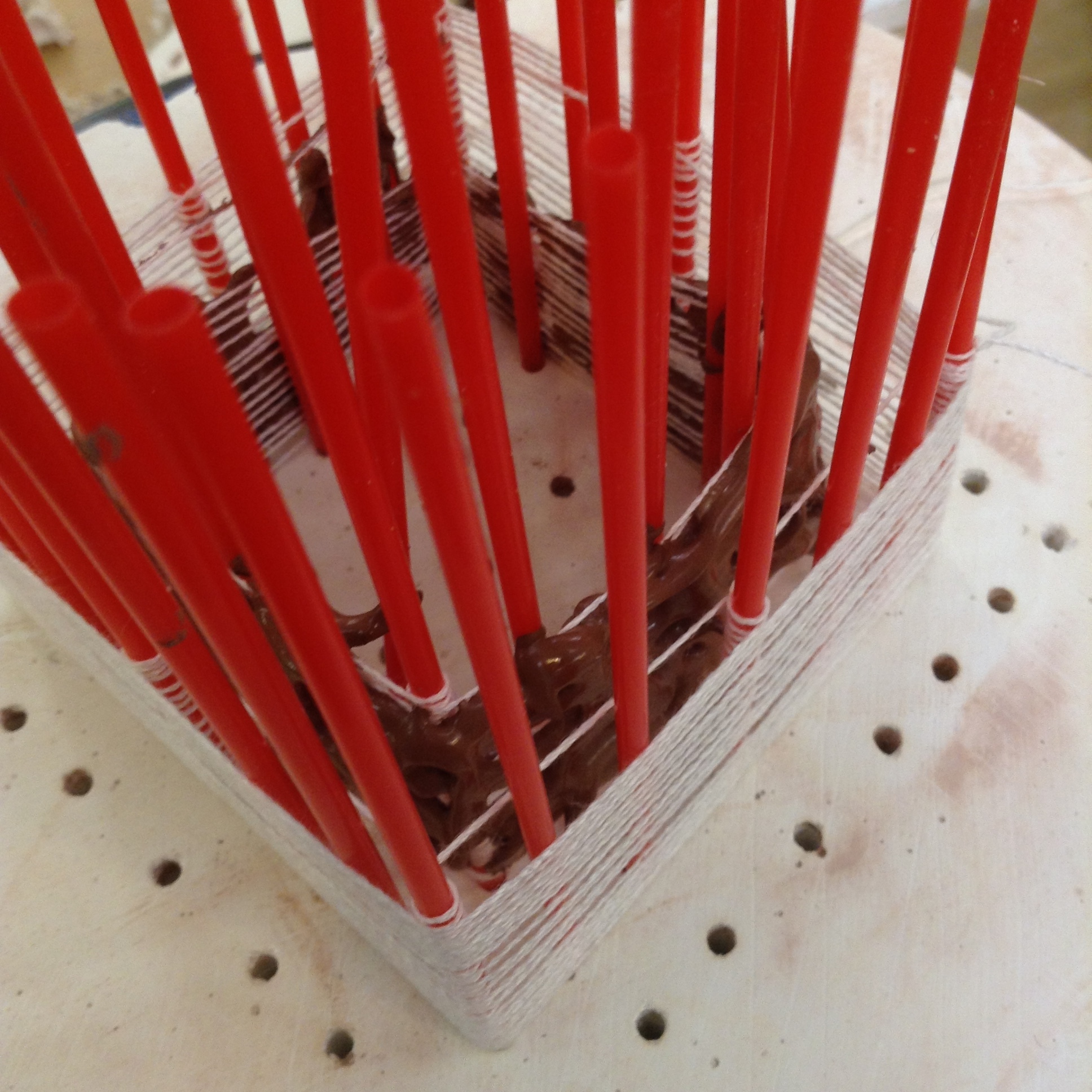

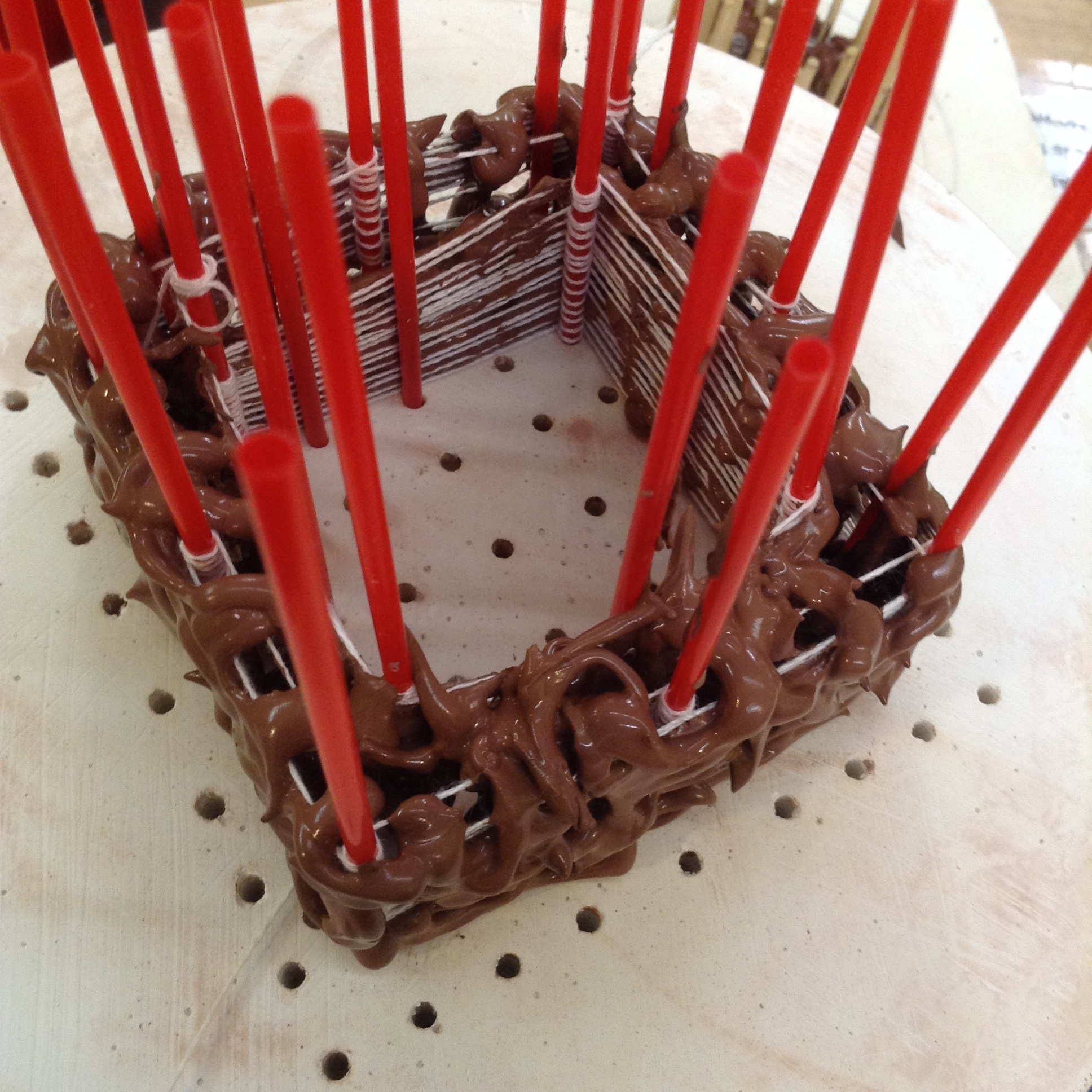

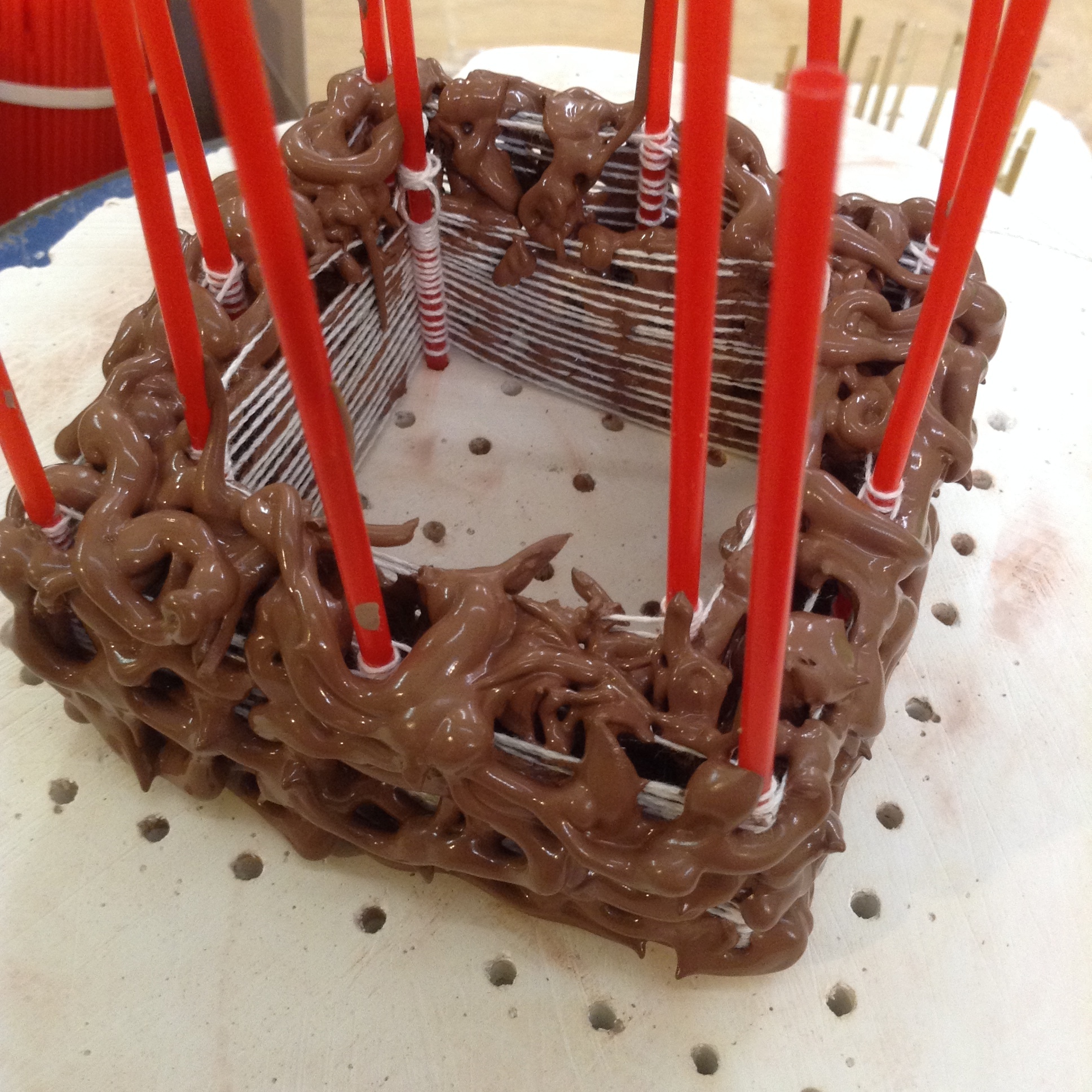

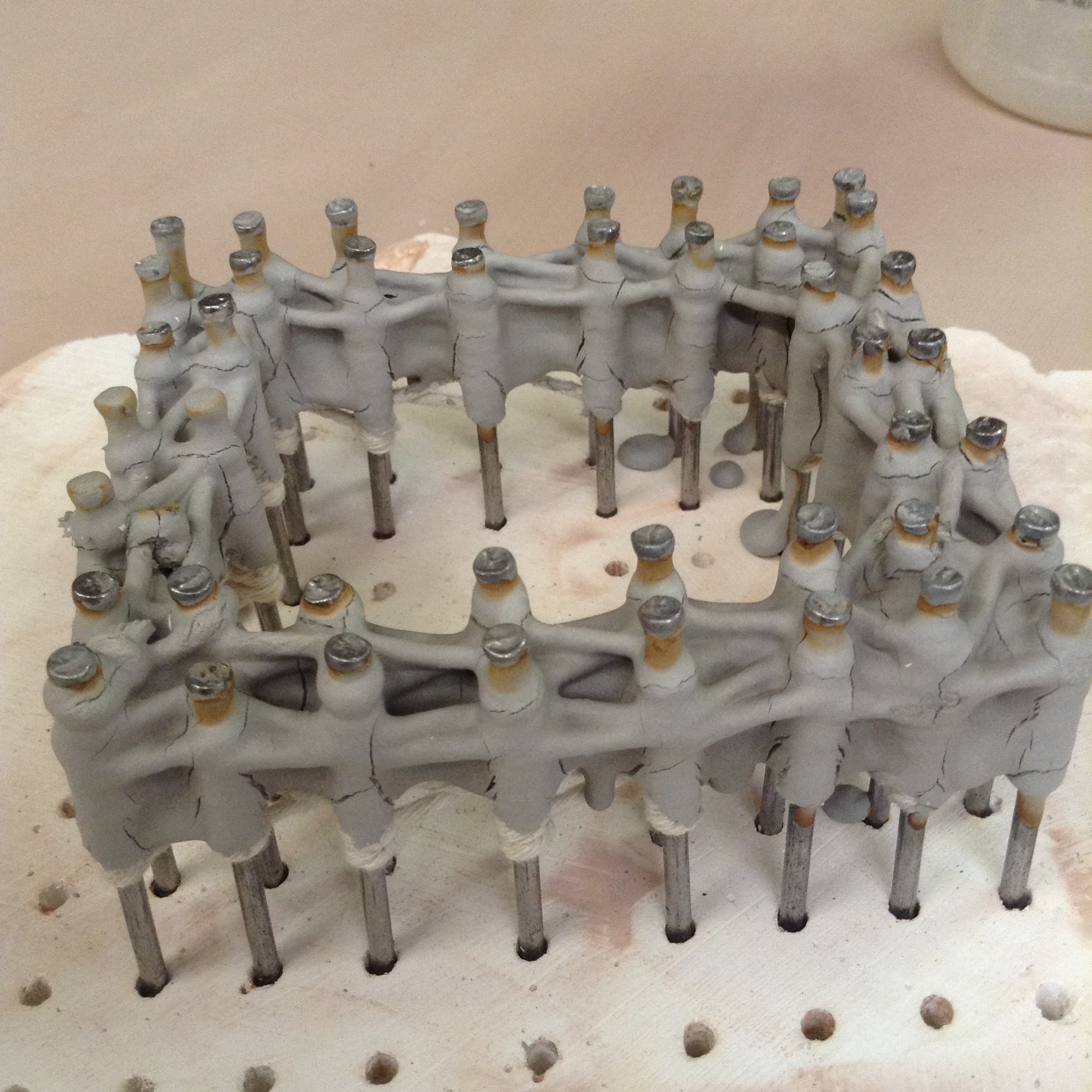

The stiffest recipes I used started from already-dense casting slip, and could be shaped like cake frosting. The basic components are dry clay powder, water, and chemicals that act as suspension and flow helpers (called deflocculants). For myself, I have used casting slip which is already fluid, and added a little vinegar to it which makes it slightly more syrupy to keep it from sagging when I'm laying out lines.

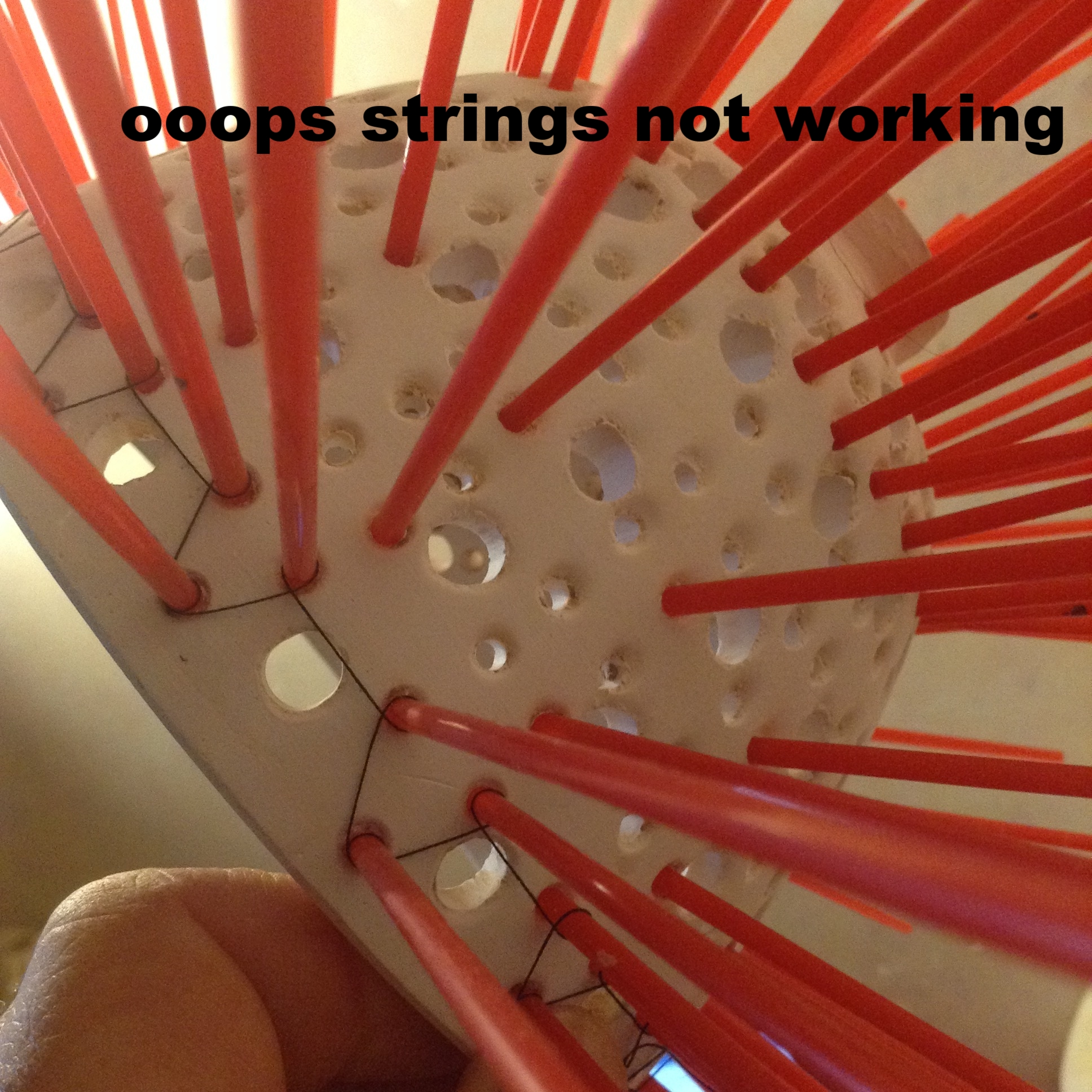

SQUEEZE BOTTLE PROBLEMS

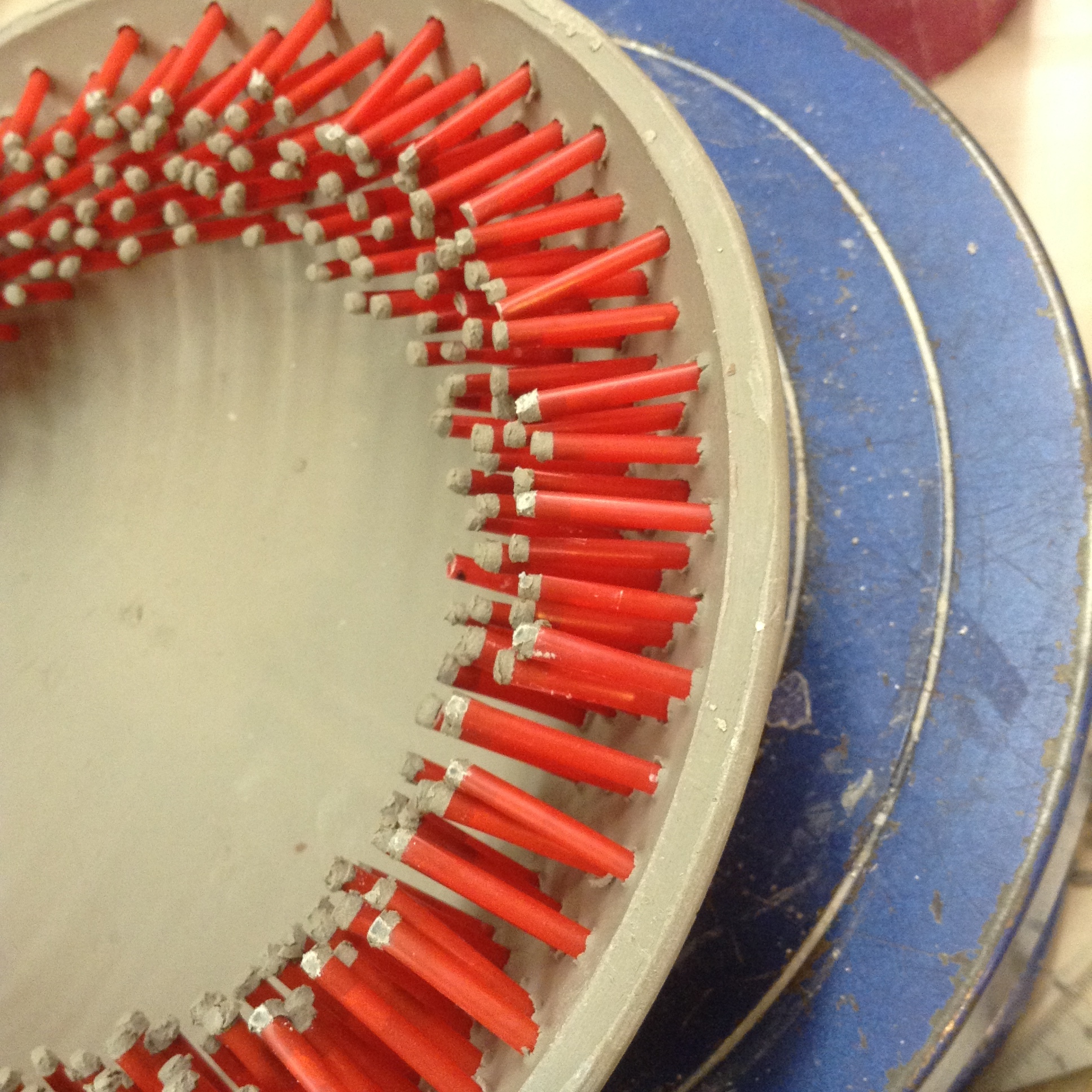

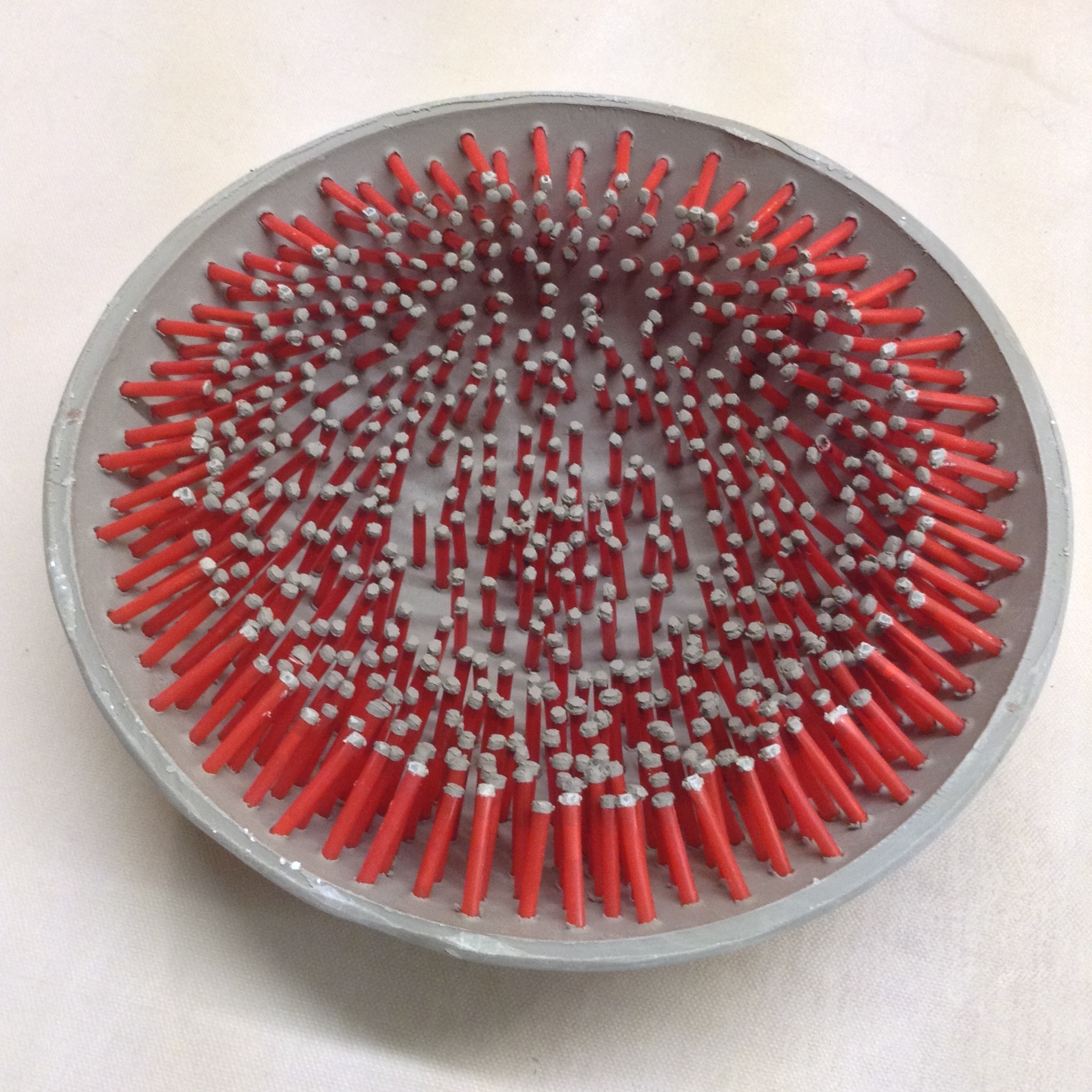

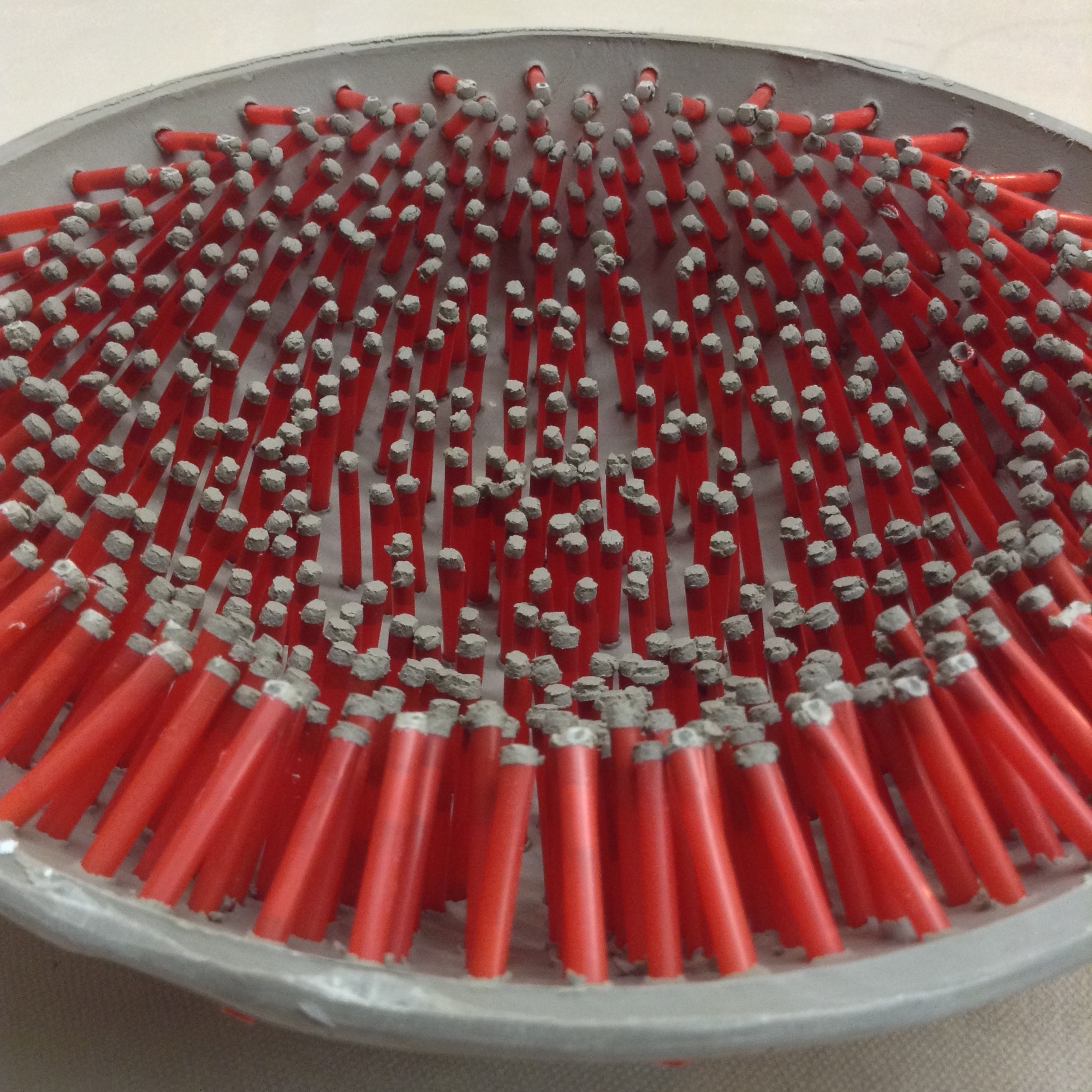

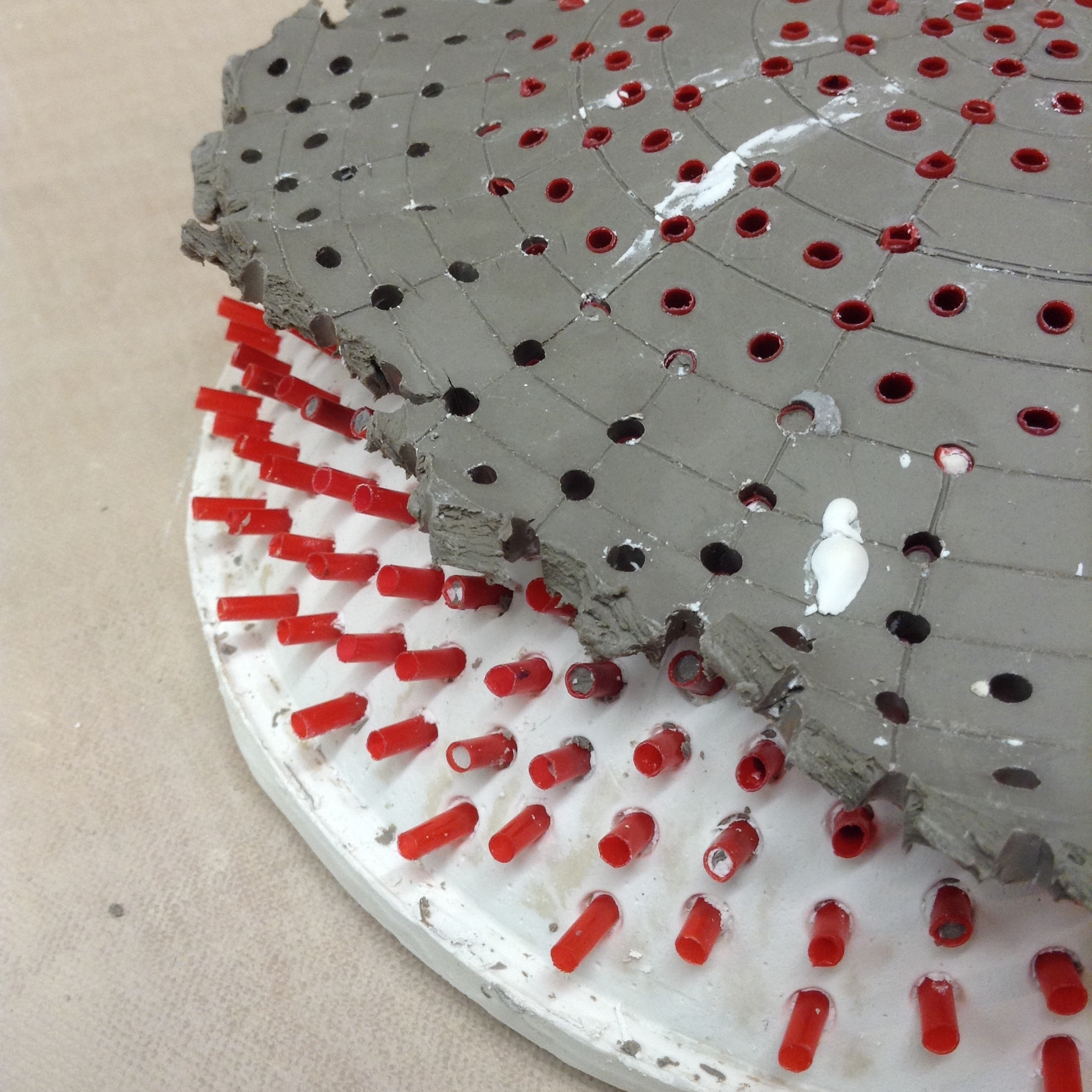

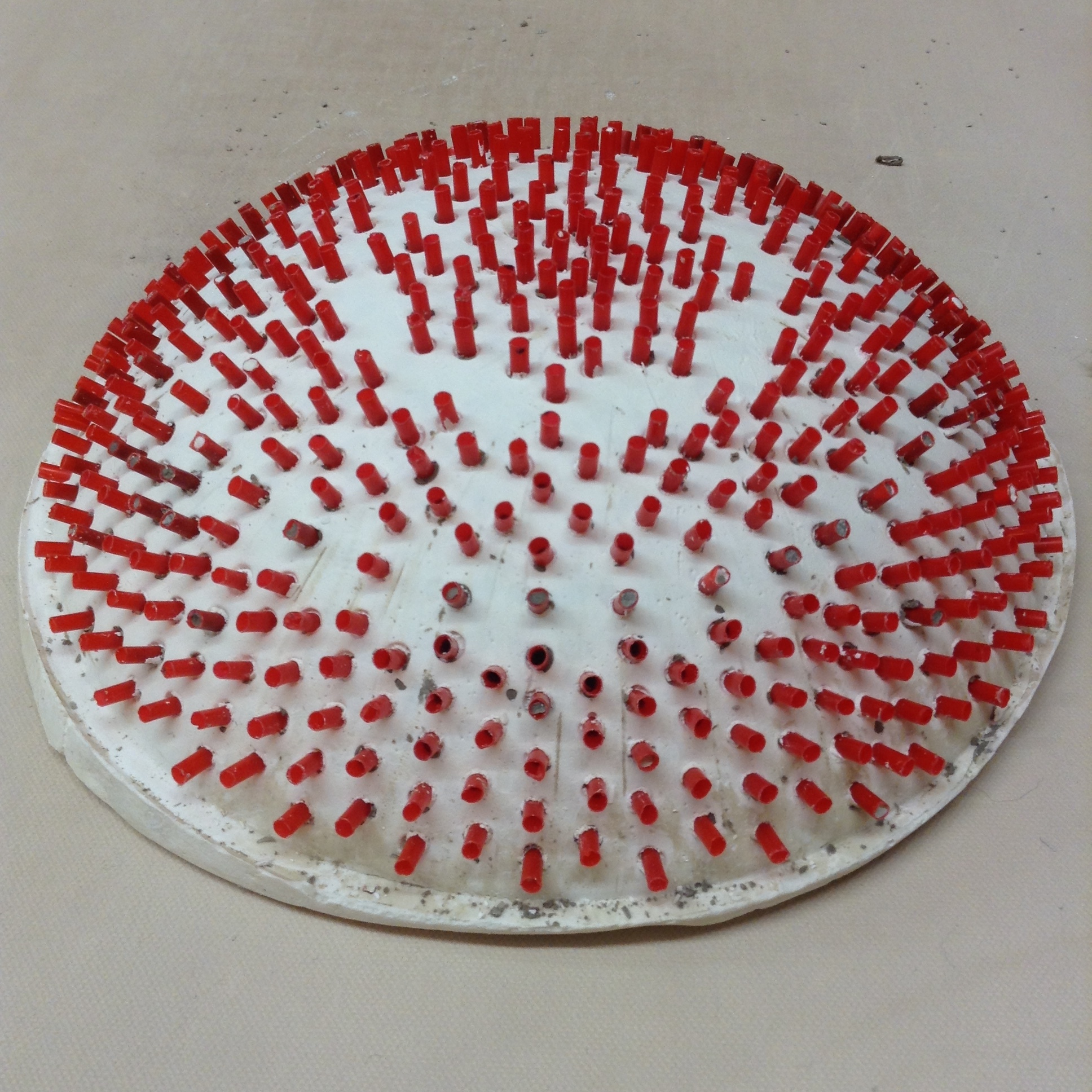

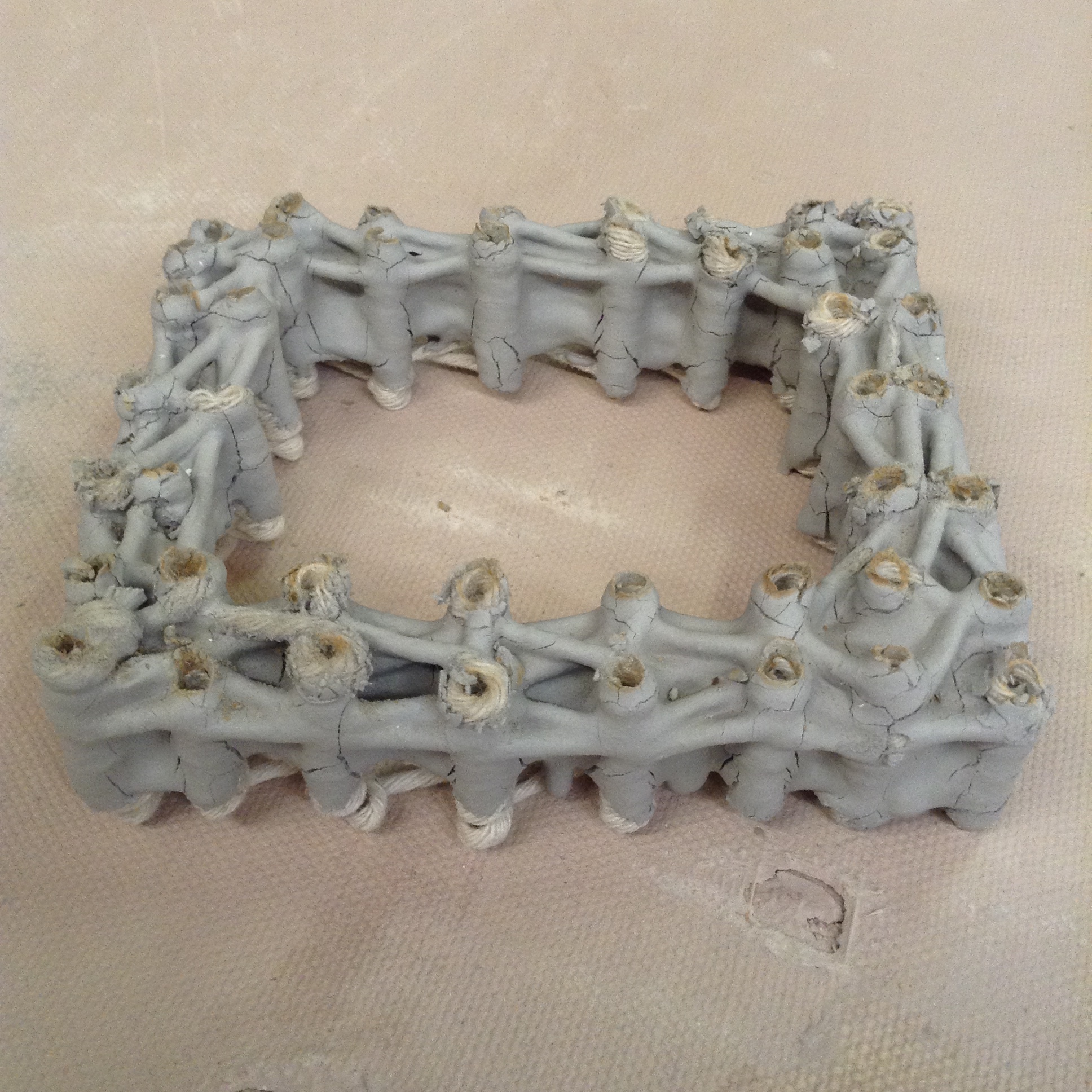

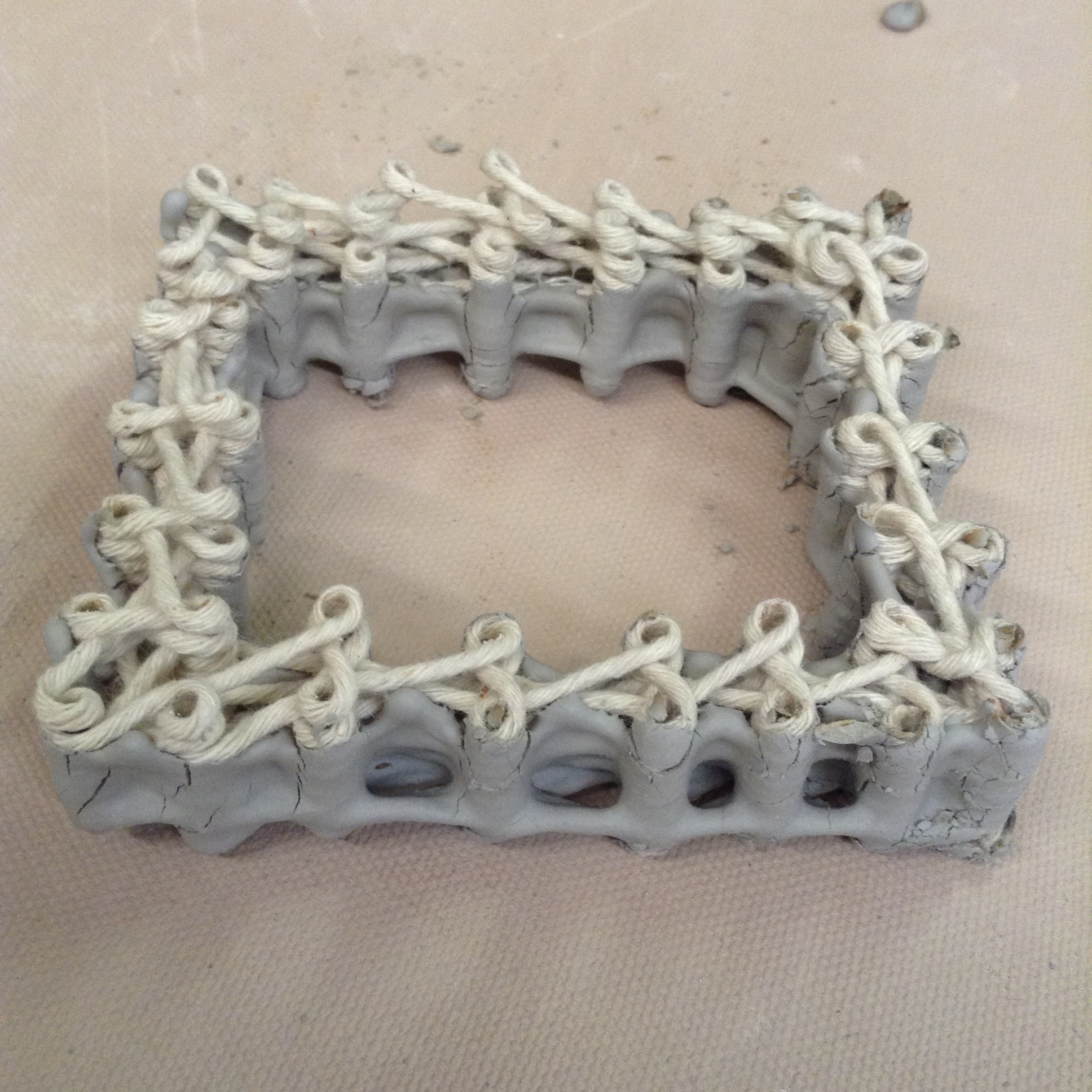

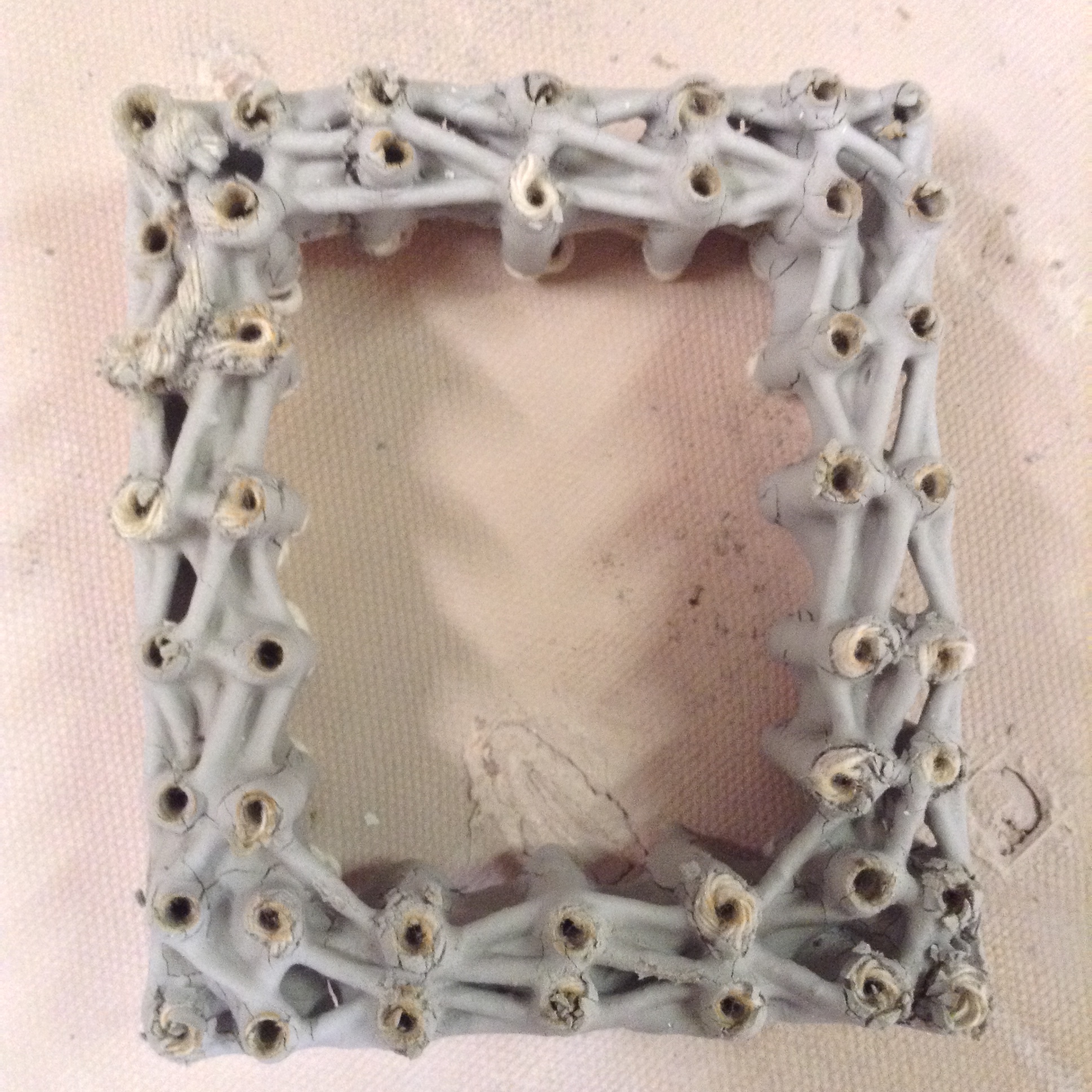

I realized the awkward way that the slip consistency plays a big role in how controlled the forms appear. For the pieces shown in this essay, I had a fair amount of control over the consistency, but there's clearly room for better protocols. I was impatient and often got globby slip, but at least I know what to do when I want slip that won't squeeze out of the bottle evenly!

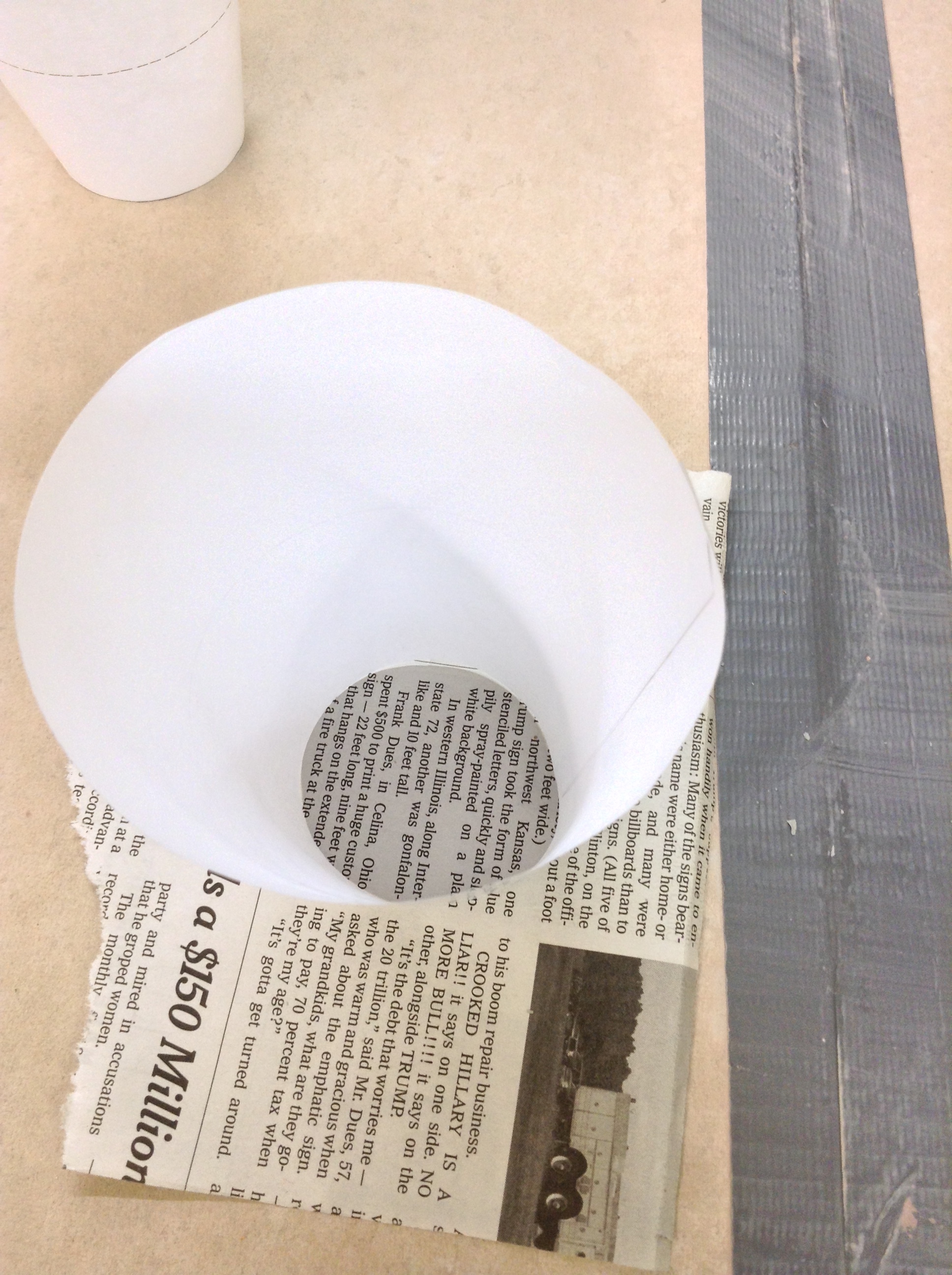

Just a bit of helpful advice: Mix your slip first in a wide container with a whisk or heavy flat utensil, before putting it into your squeeze bottle. I made the regrettable choice of adding vinegar to the squeeze bottle directly, thinking "Oh, I'll just shake it up." It mostly works, but not really.

WHY BOTHER WITH ANY OF THIS? WHY USE SMELLY SLIP WHEN HANDBUILDING PROCESSES ALREADY EXIST?

Okay, I'm already being a bit facetious: The clay slip thickened with vinegar doesn't really smell much. I've heard that these mixtures might spoil over time, but mine so far are okay.

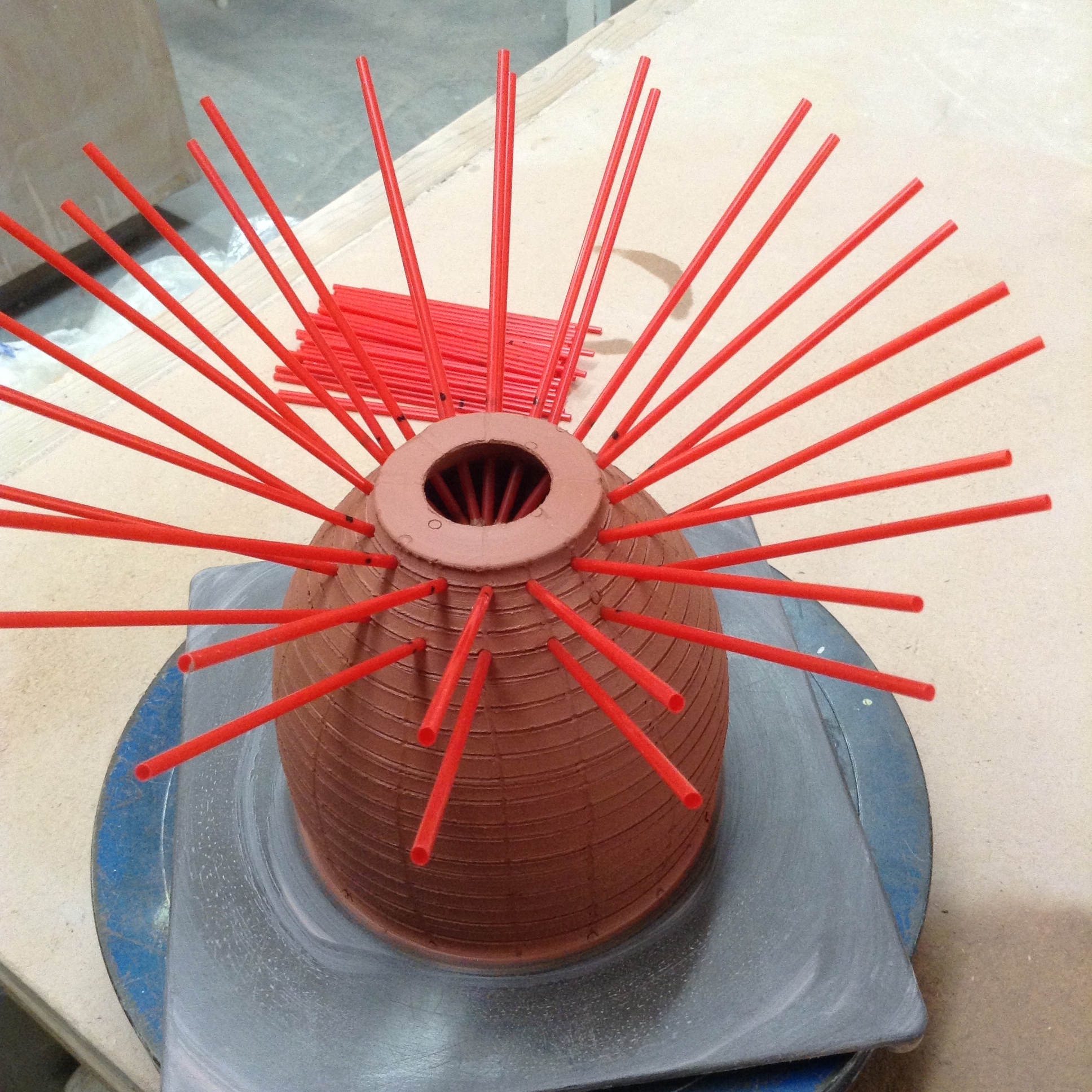

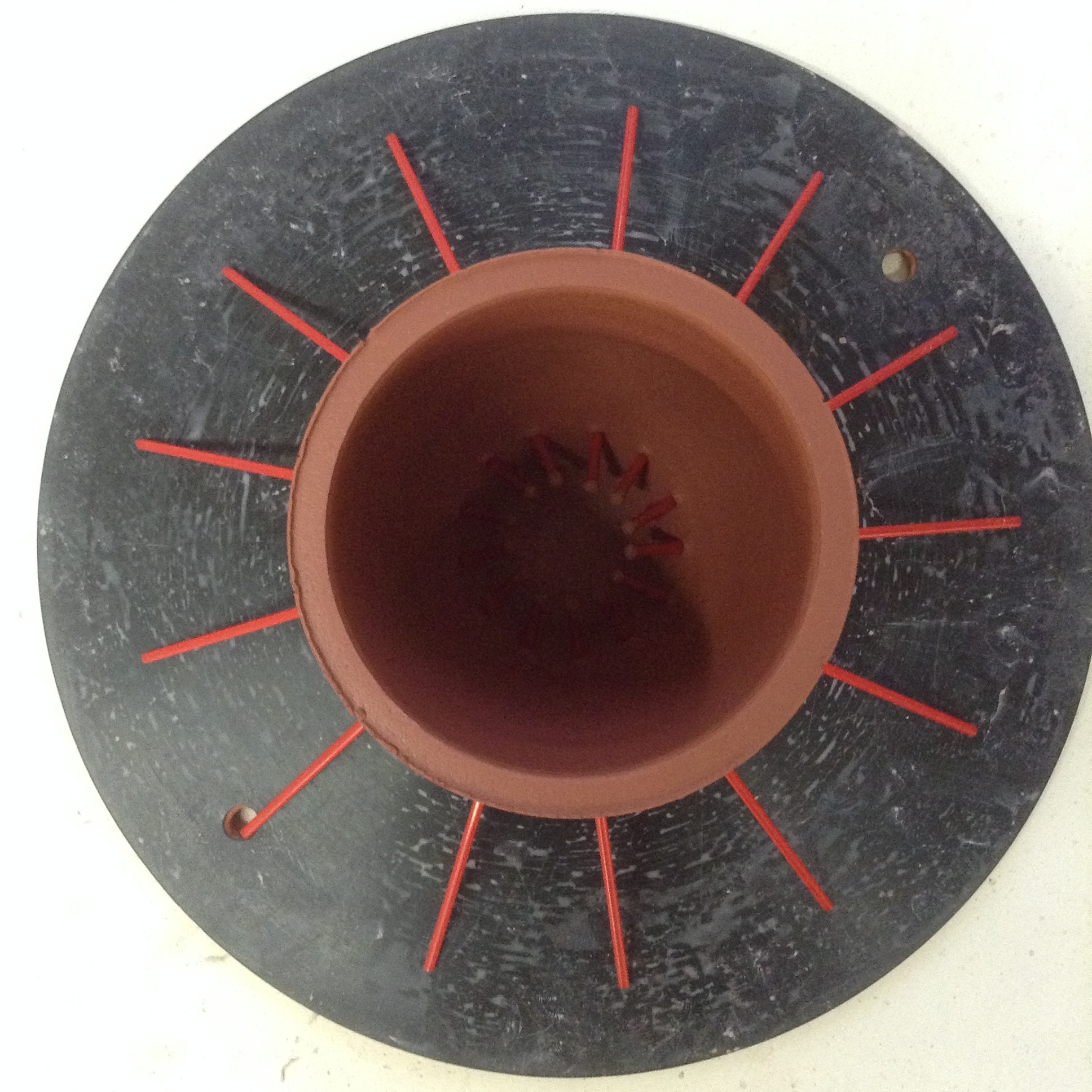

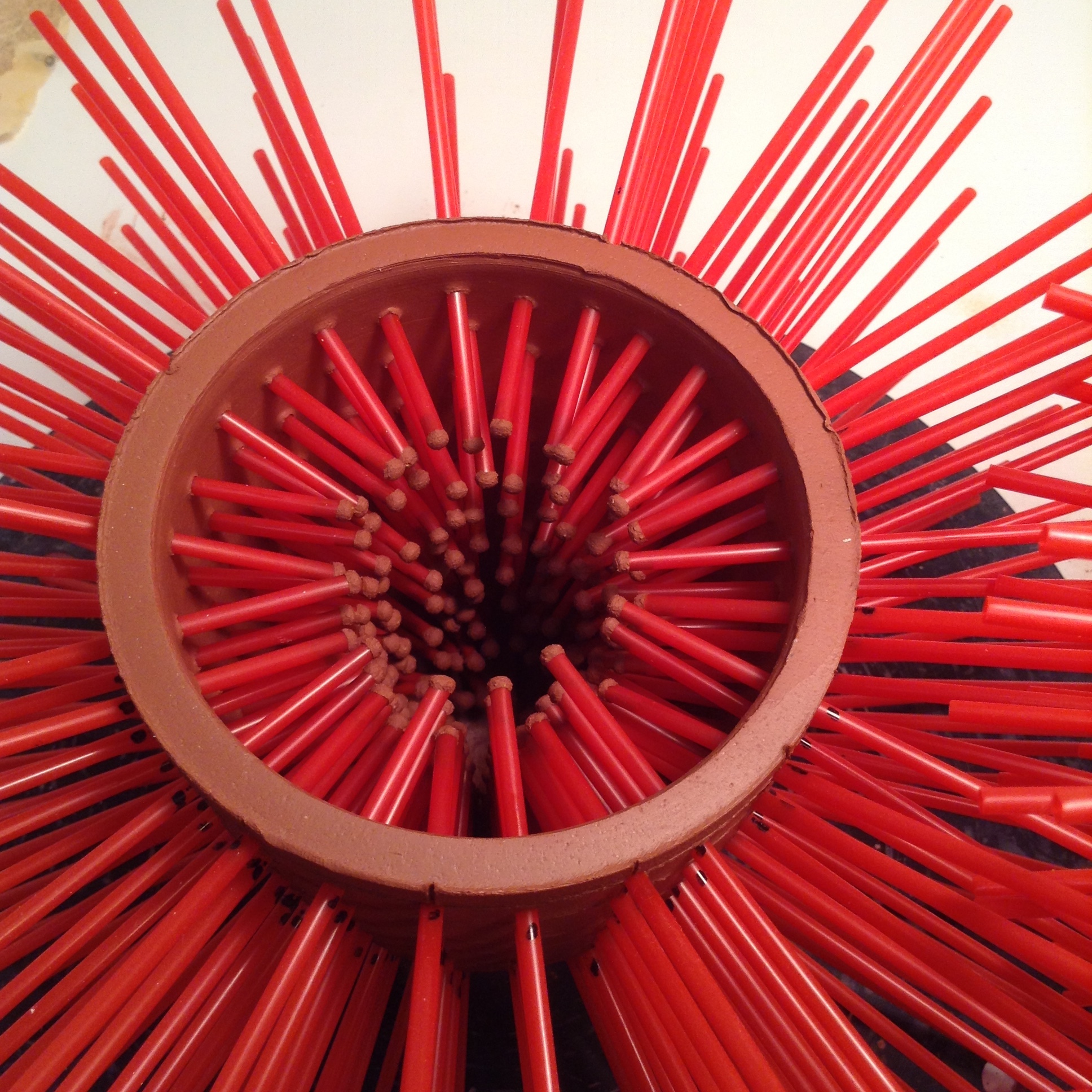

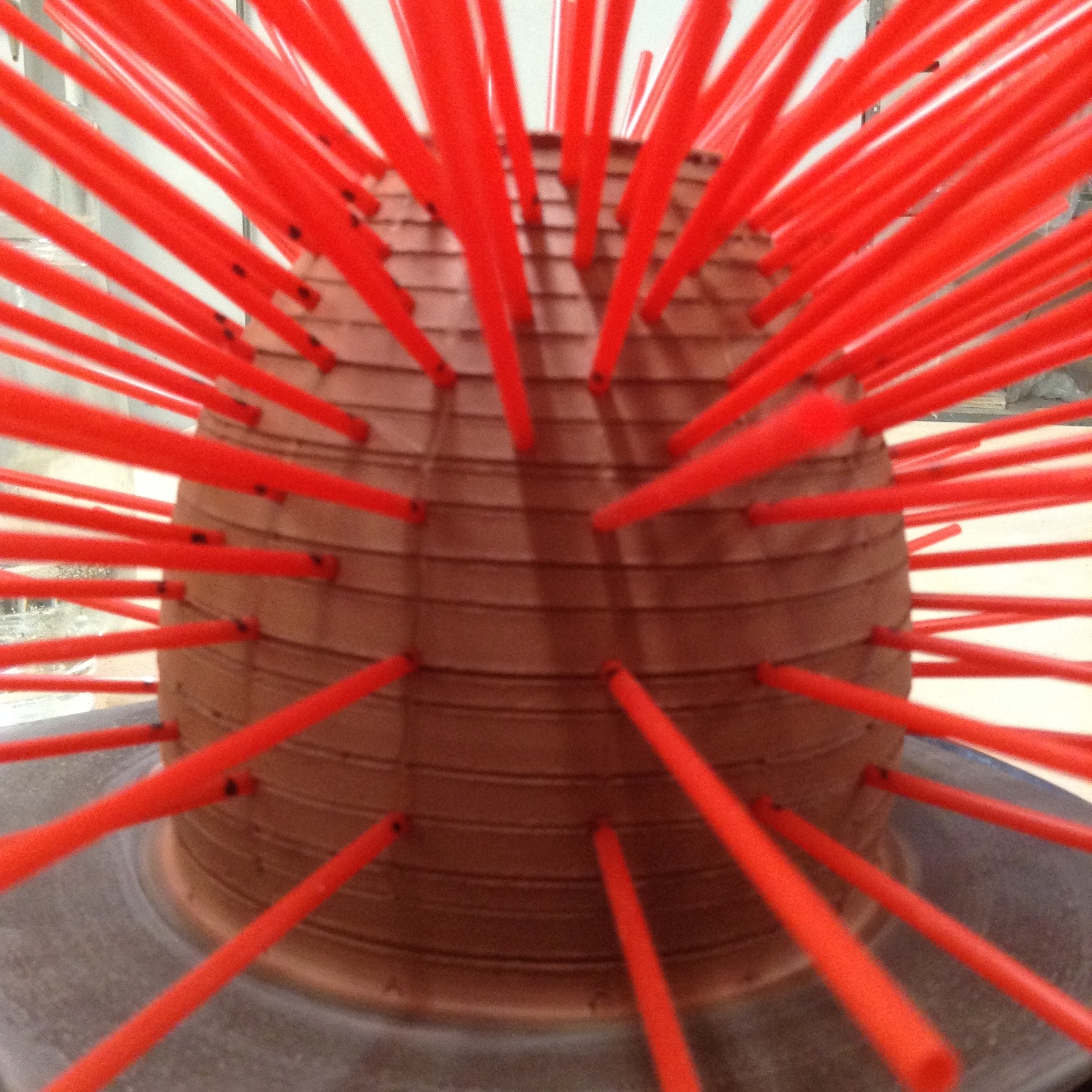

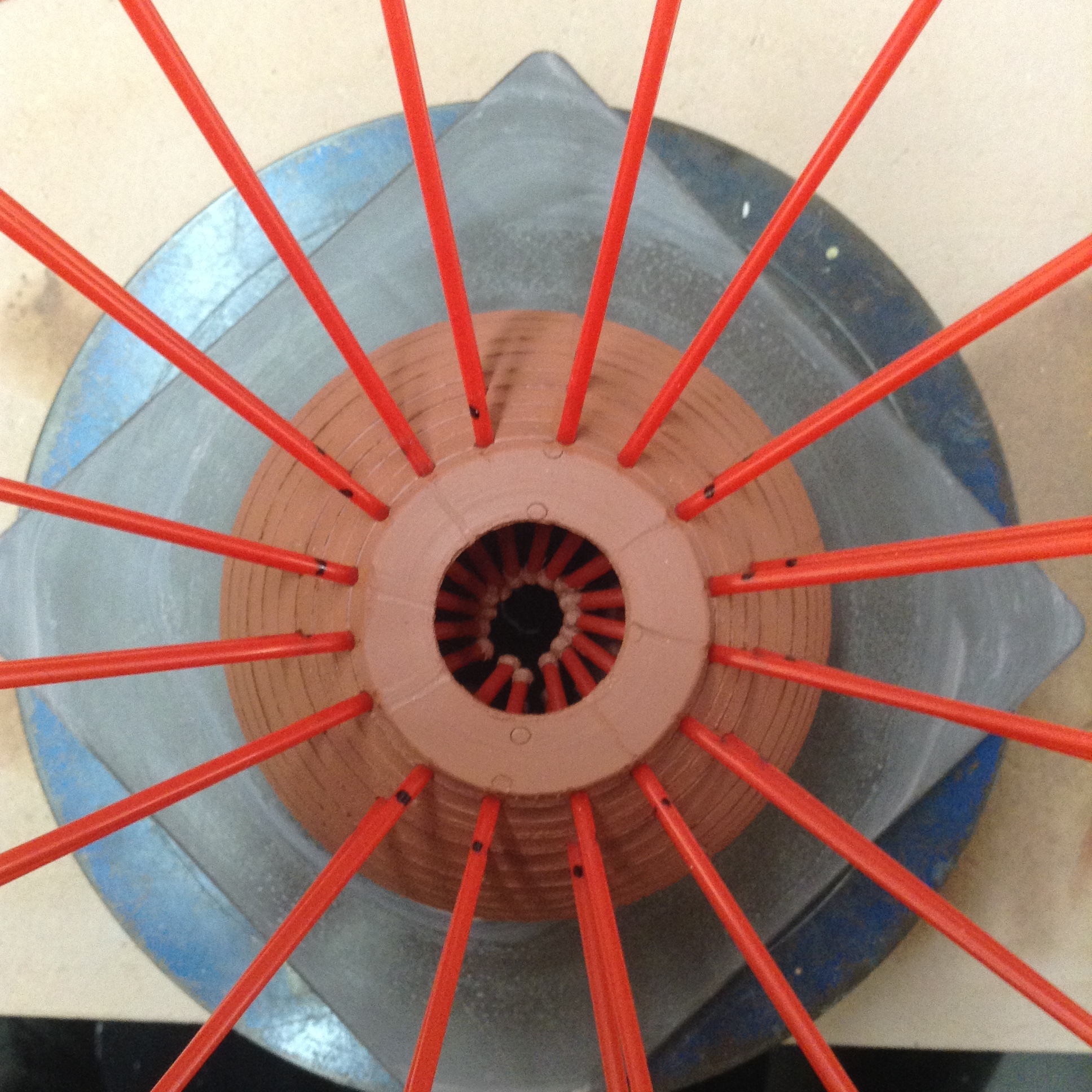

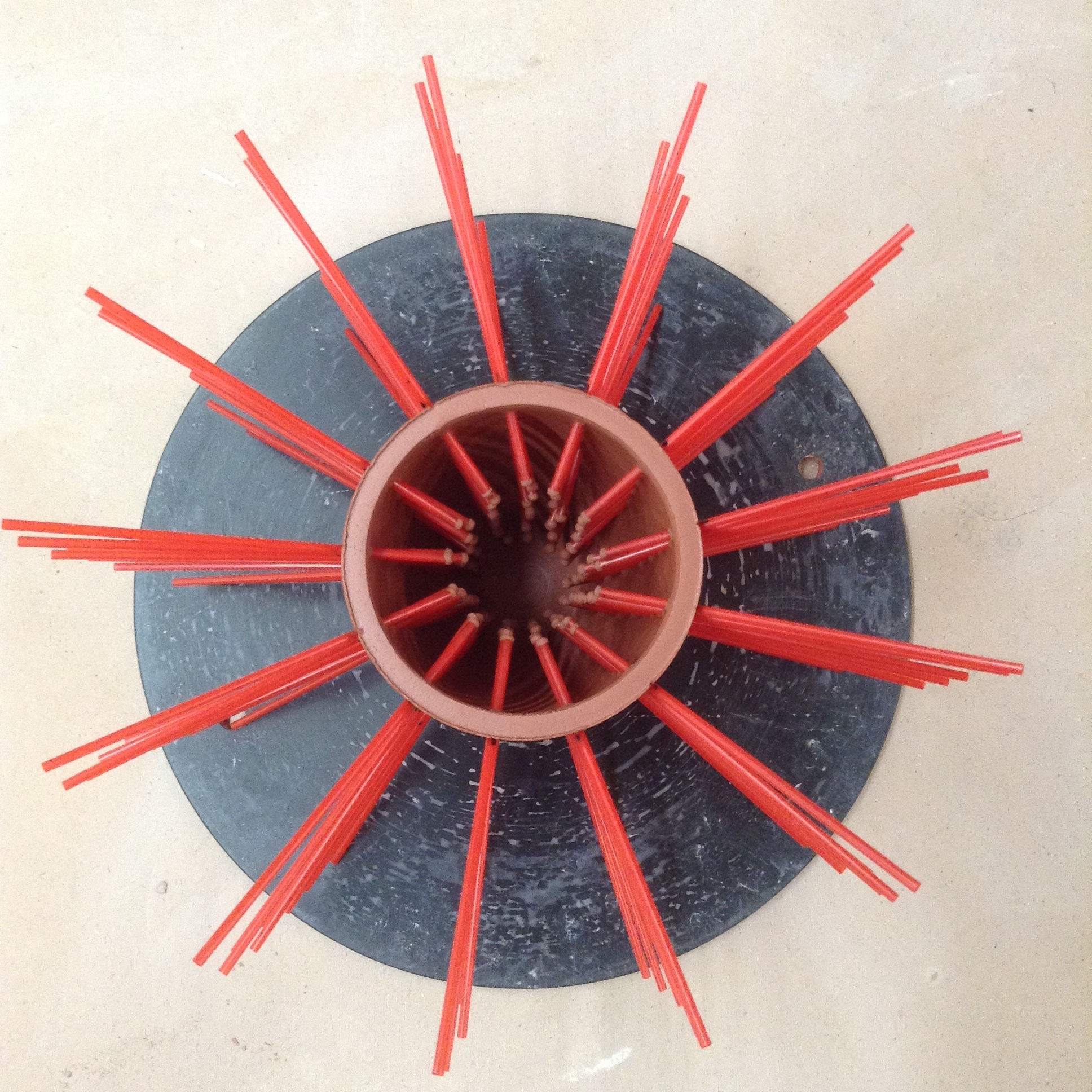

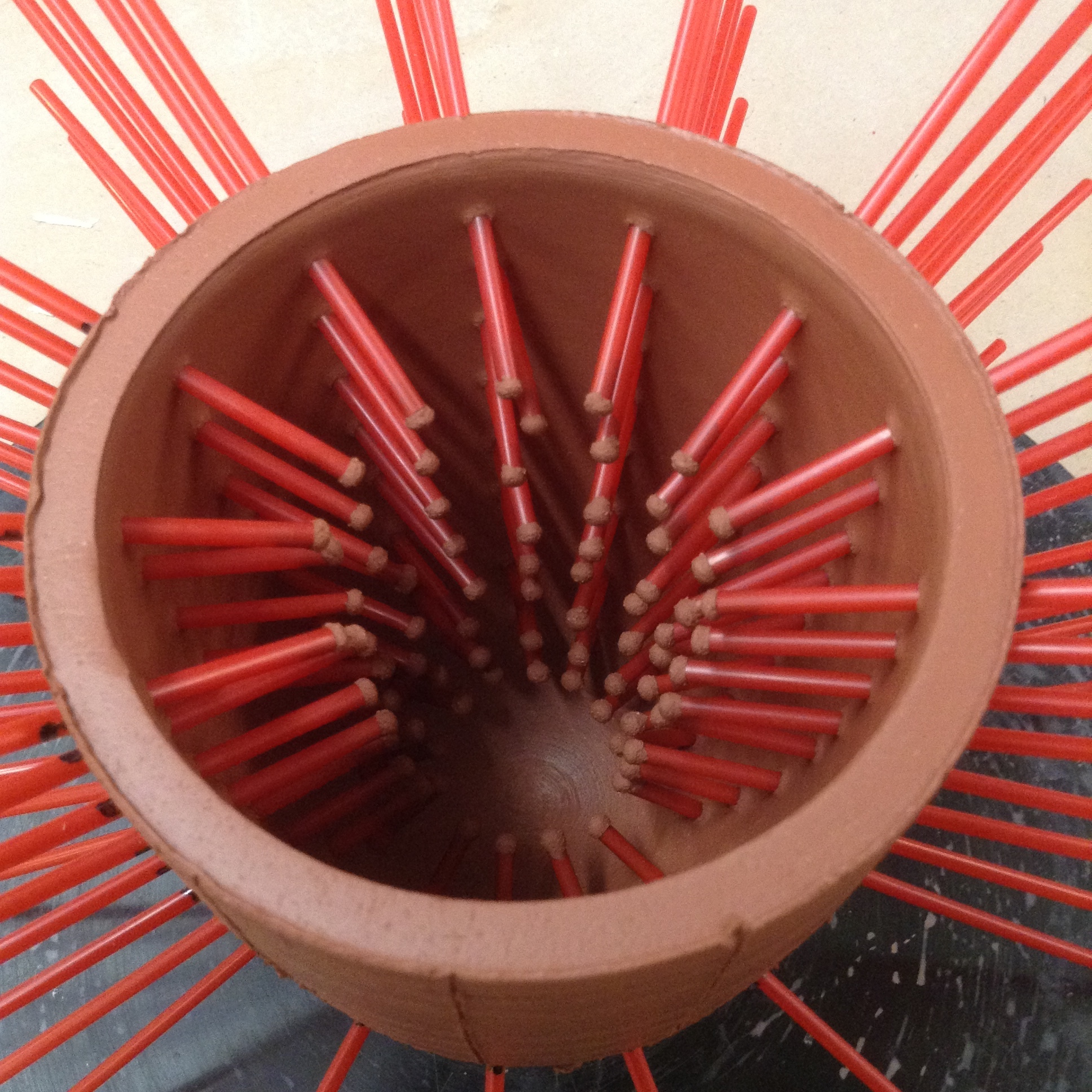

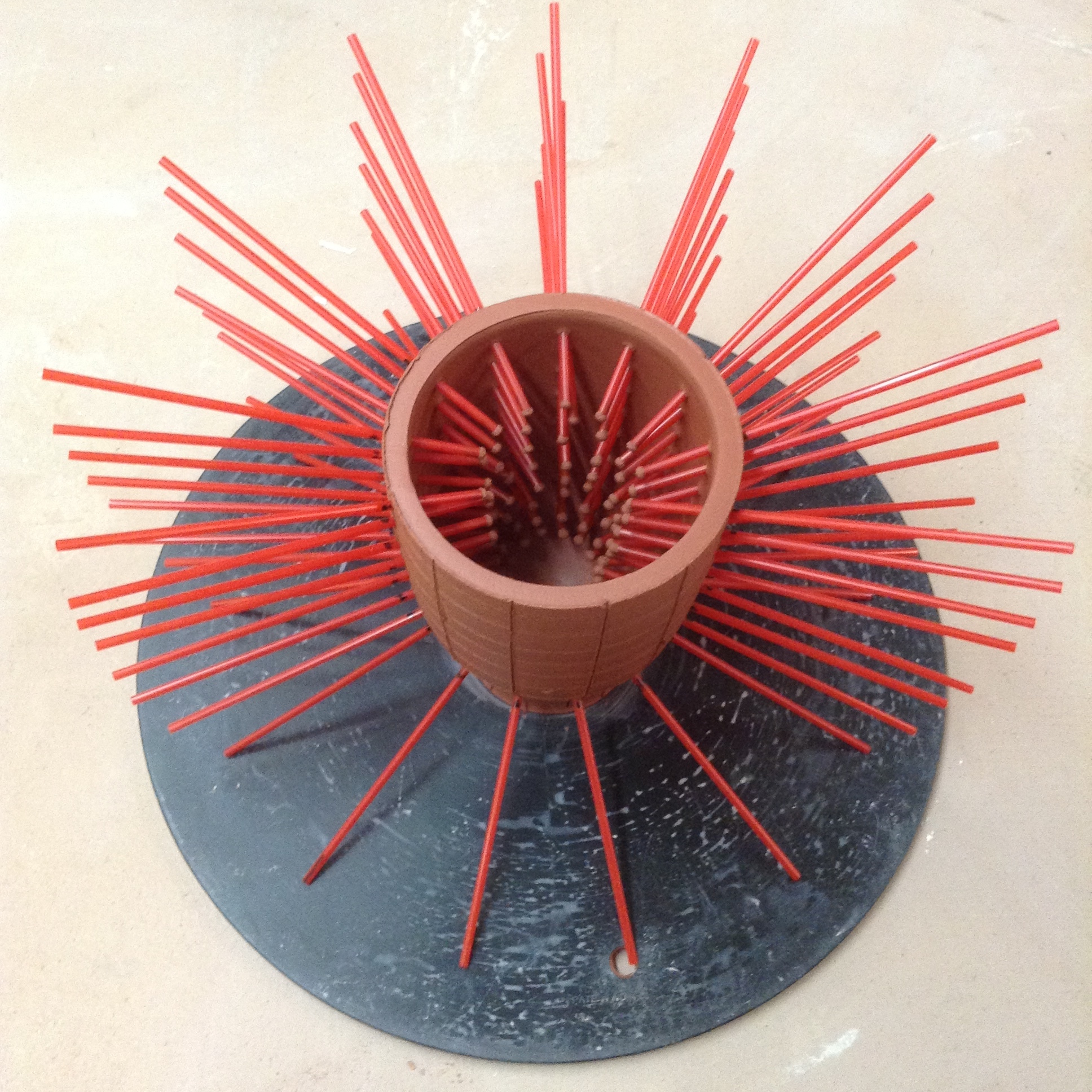

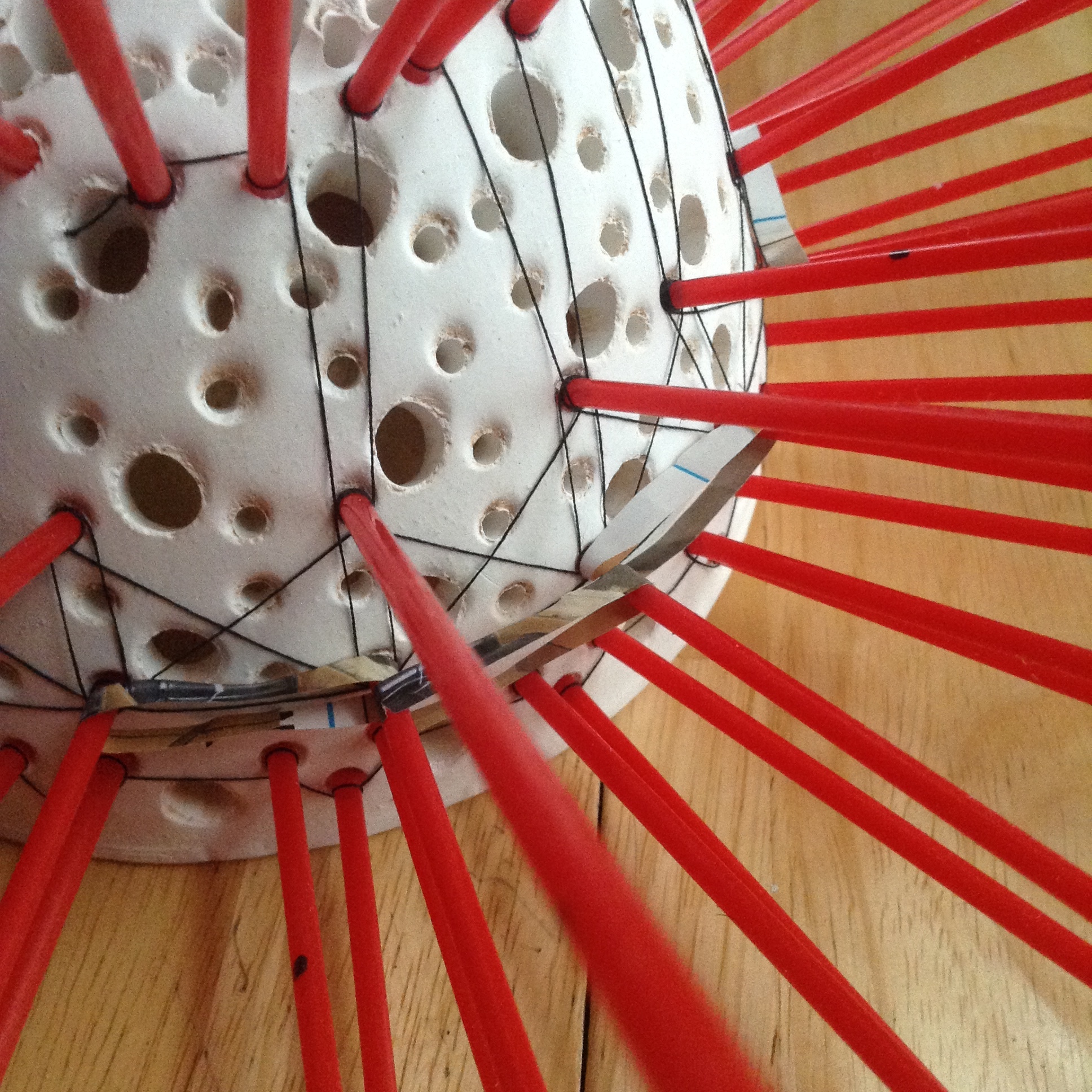

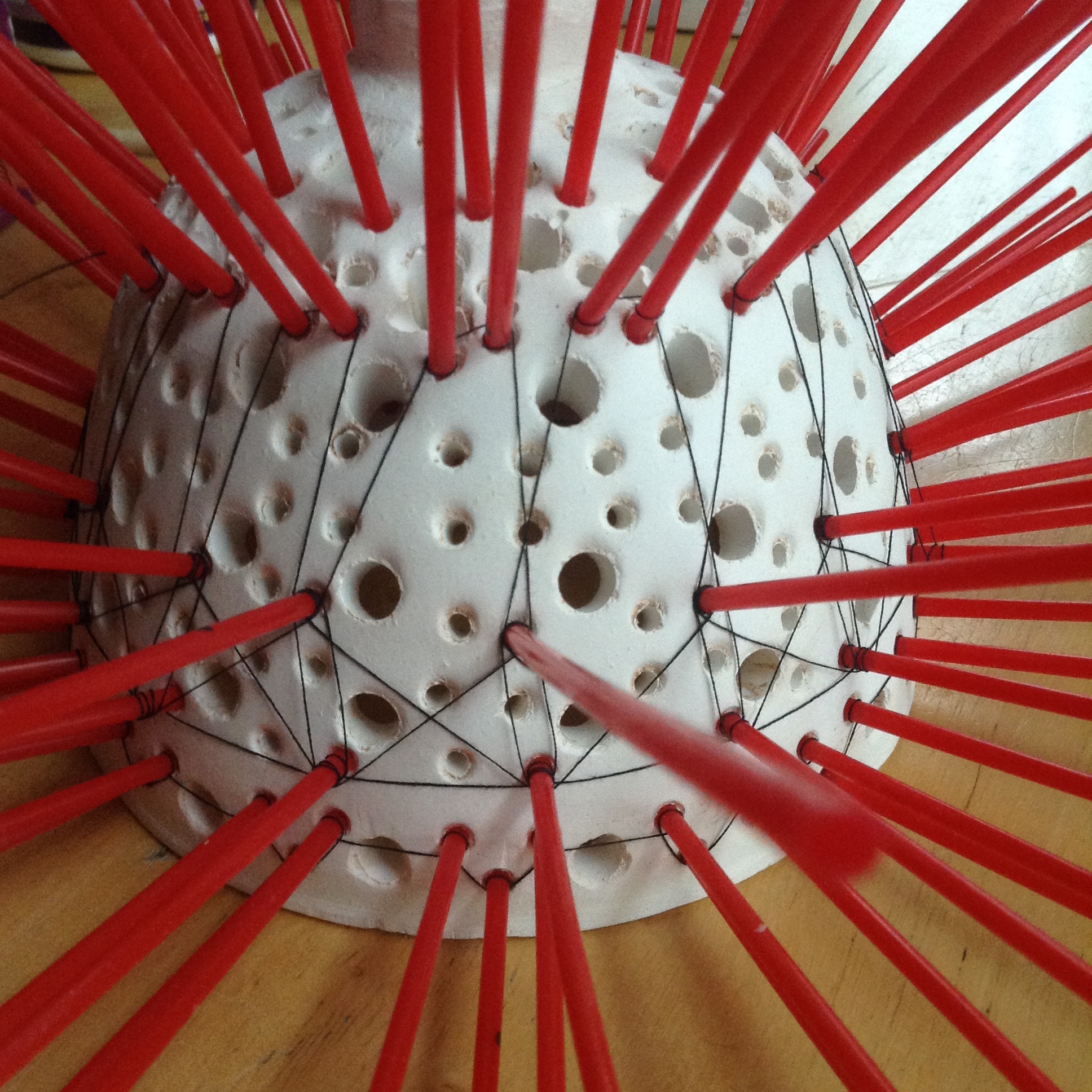

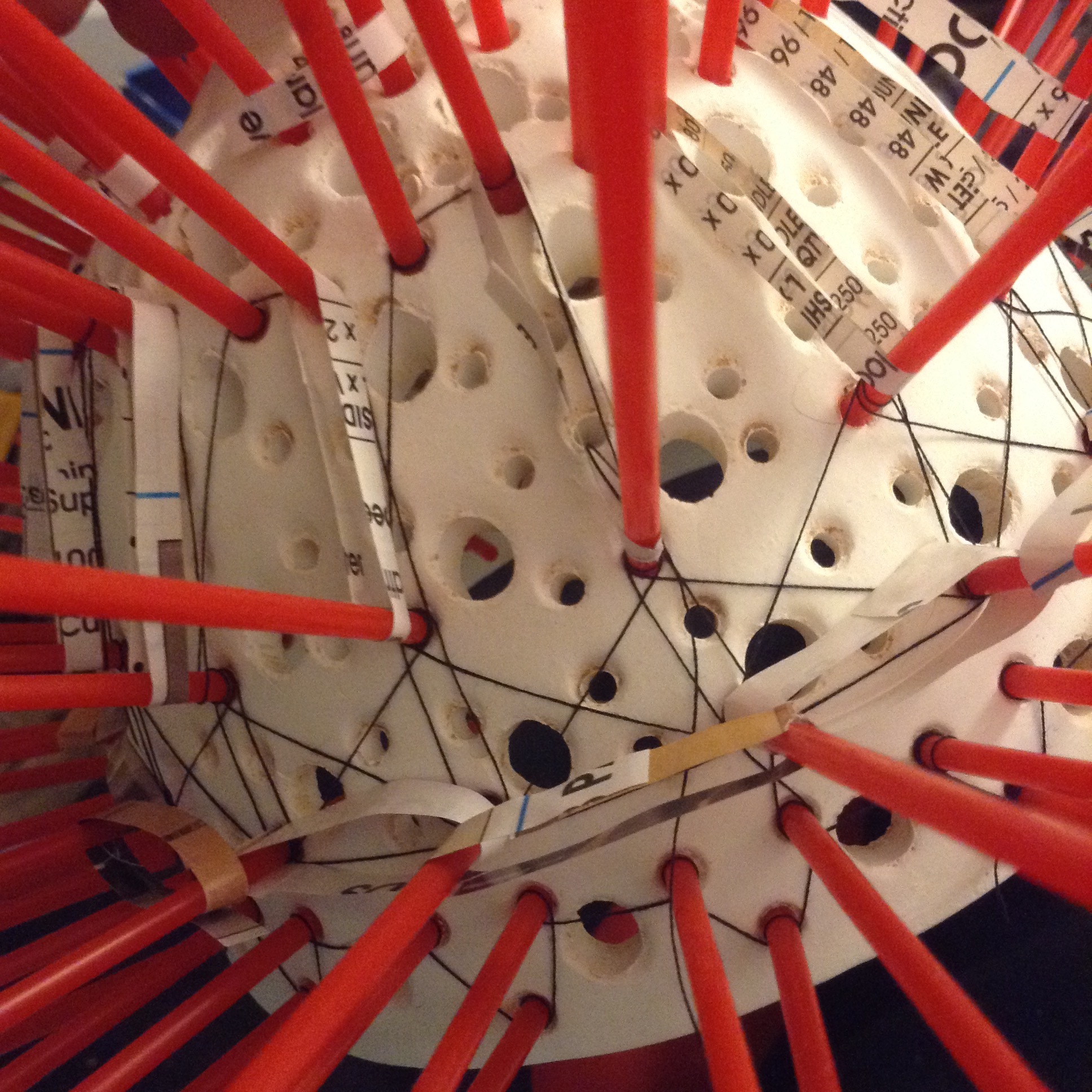

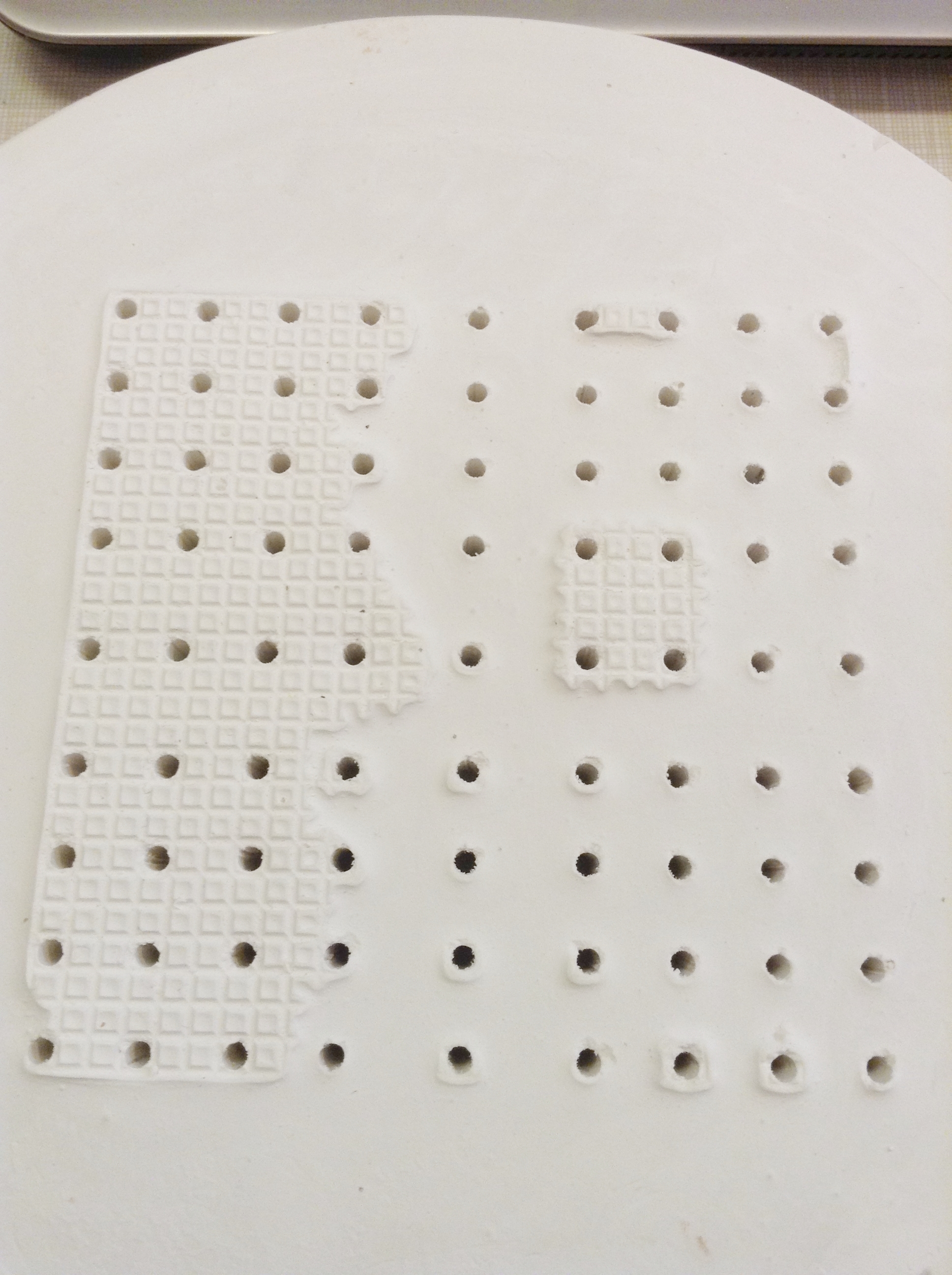

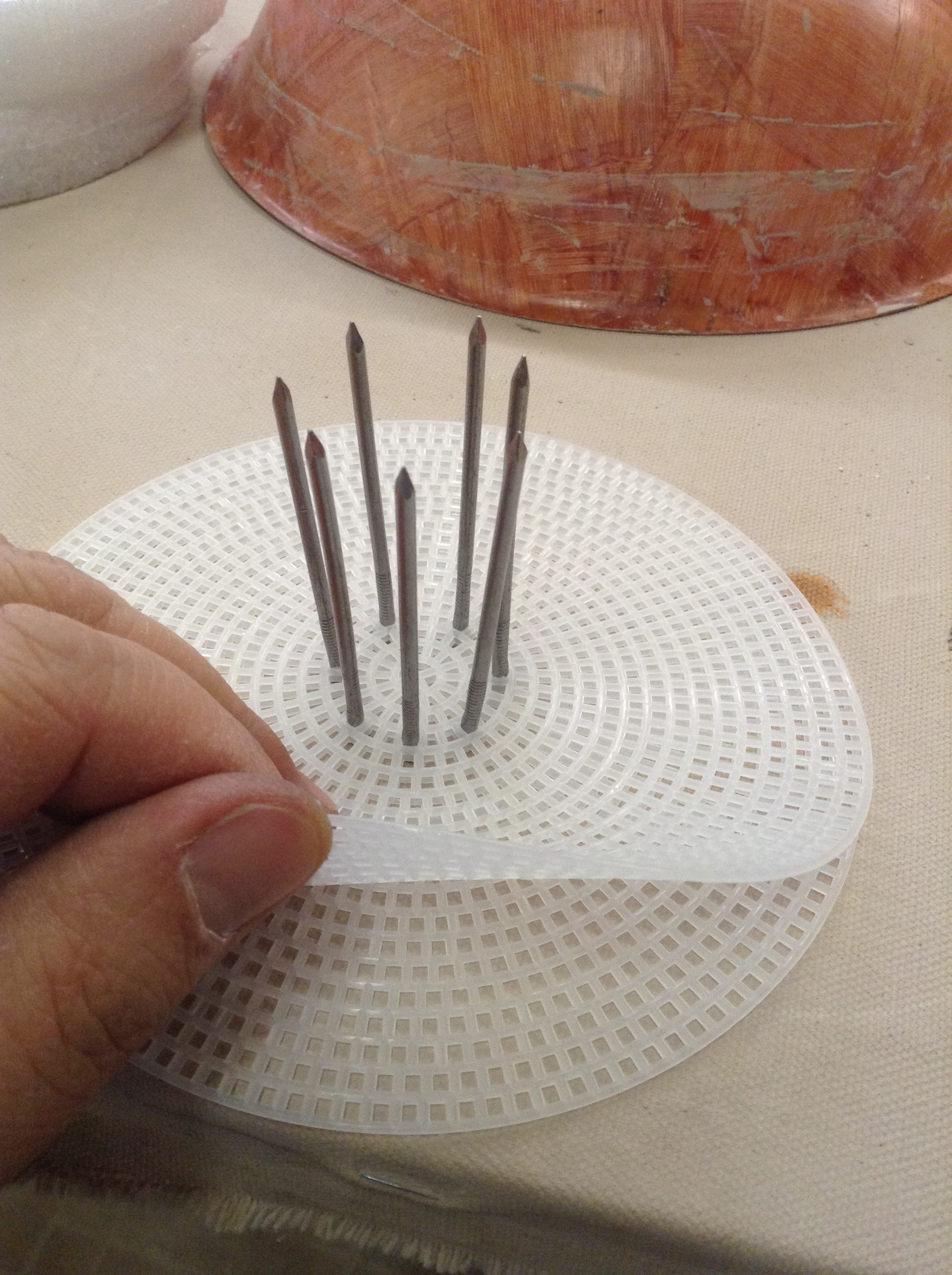

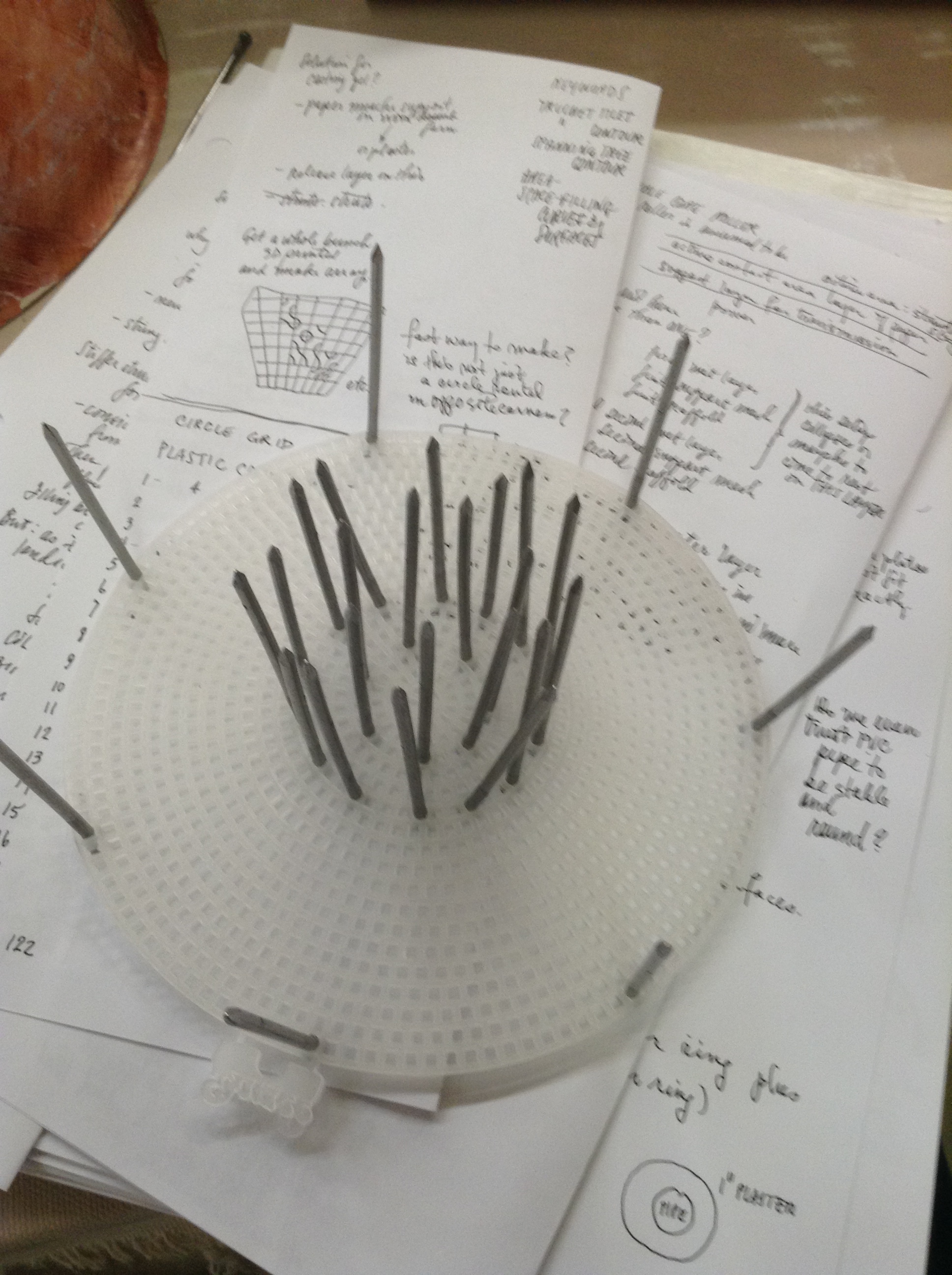

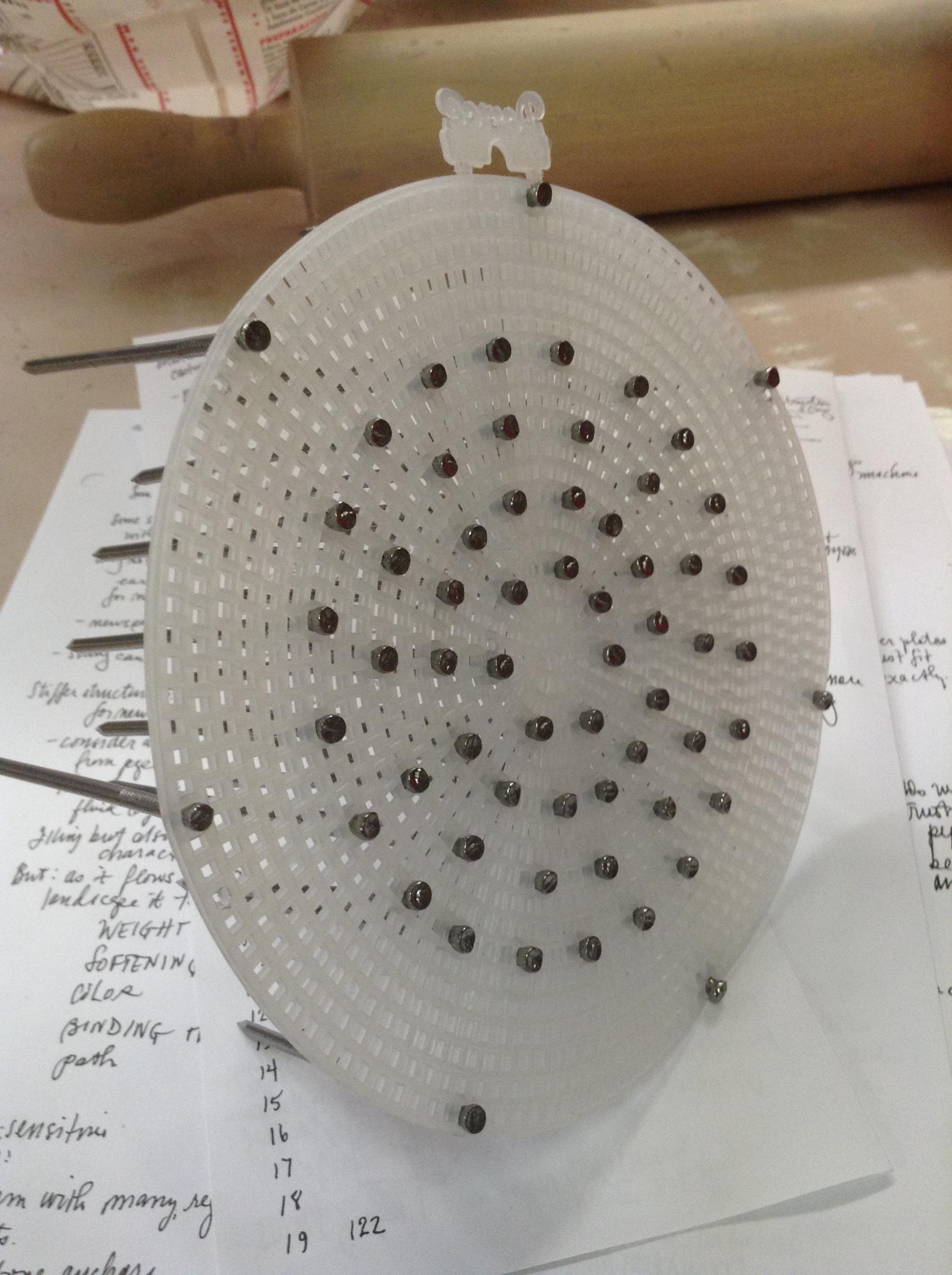

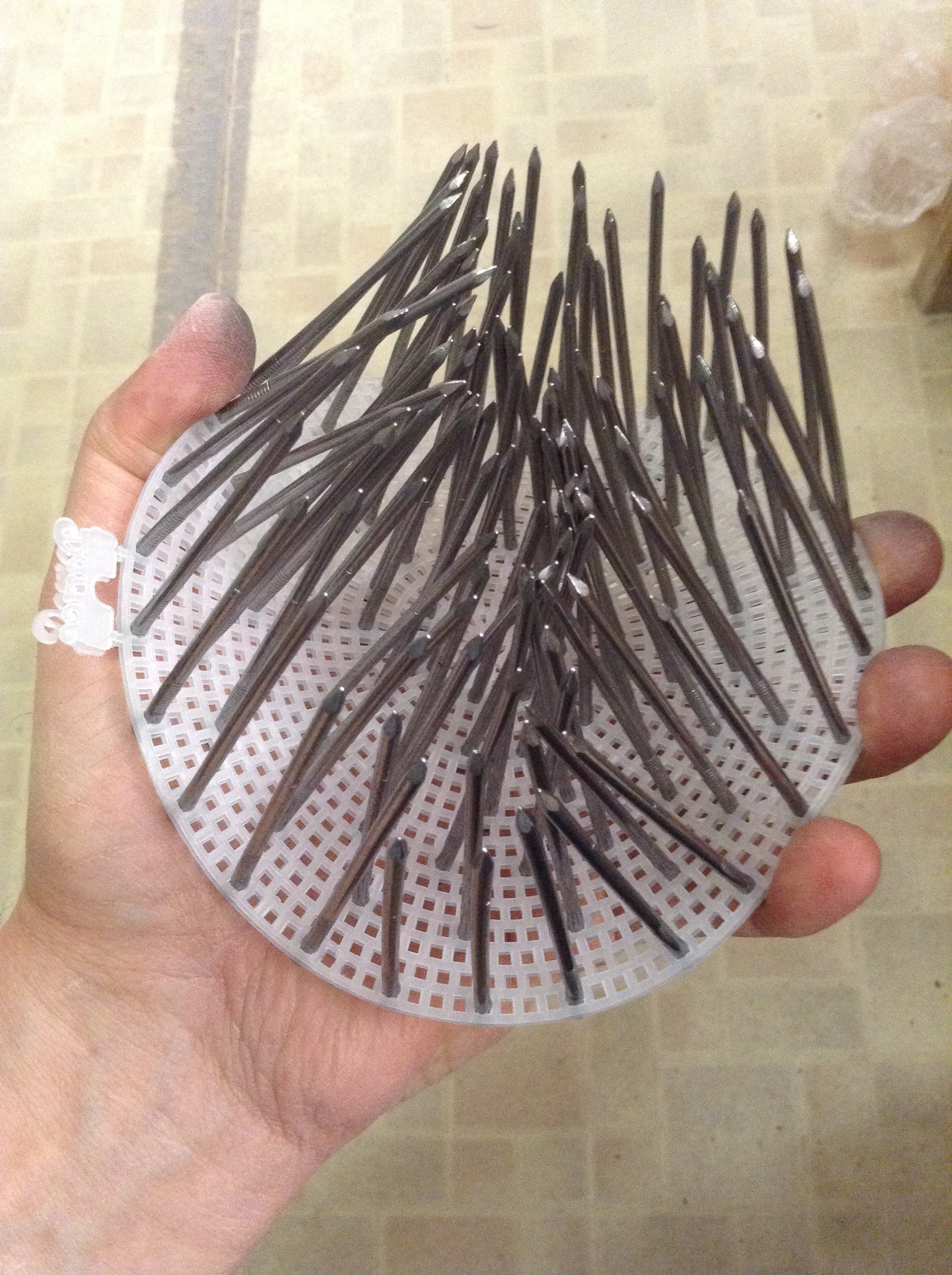

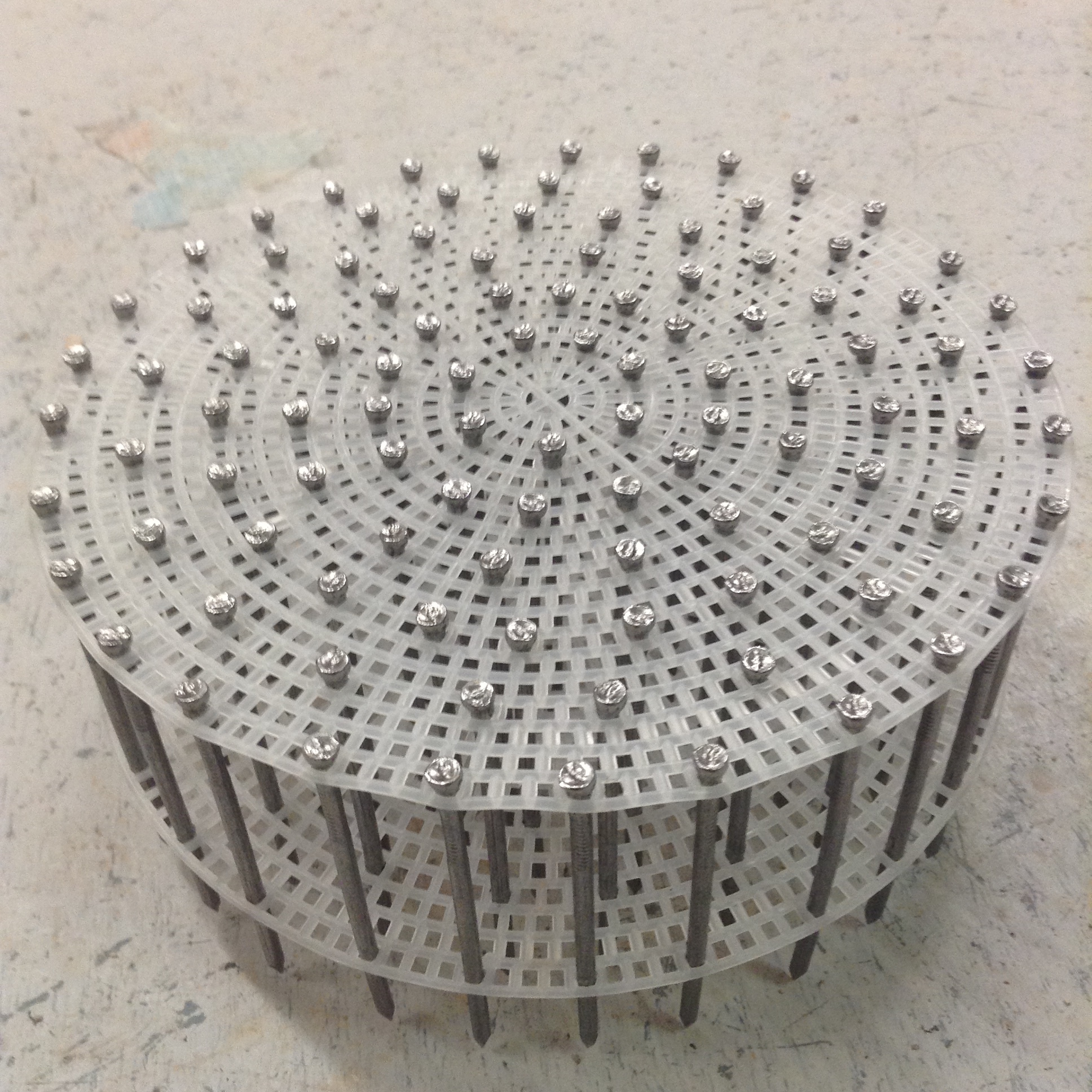

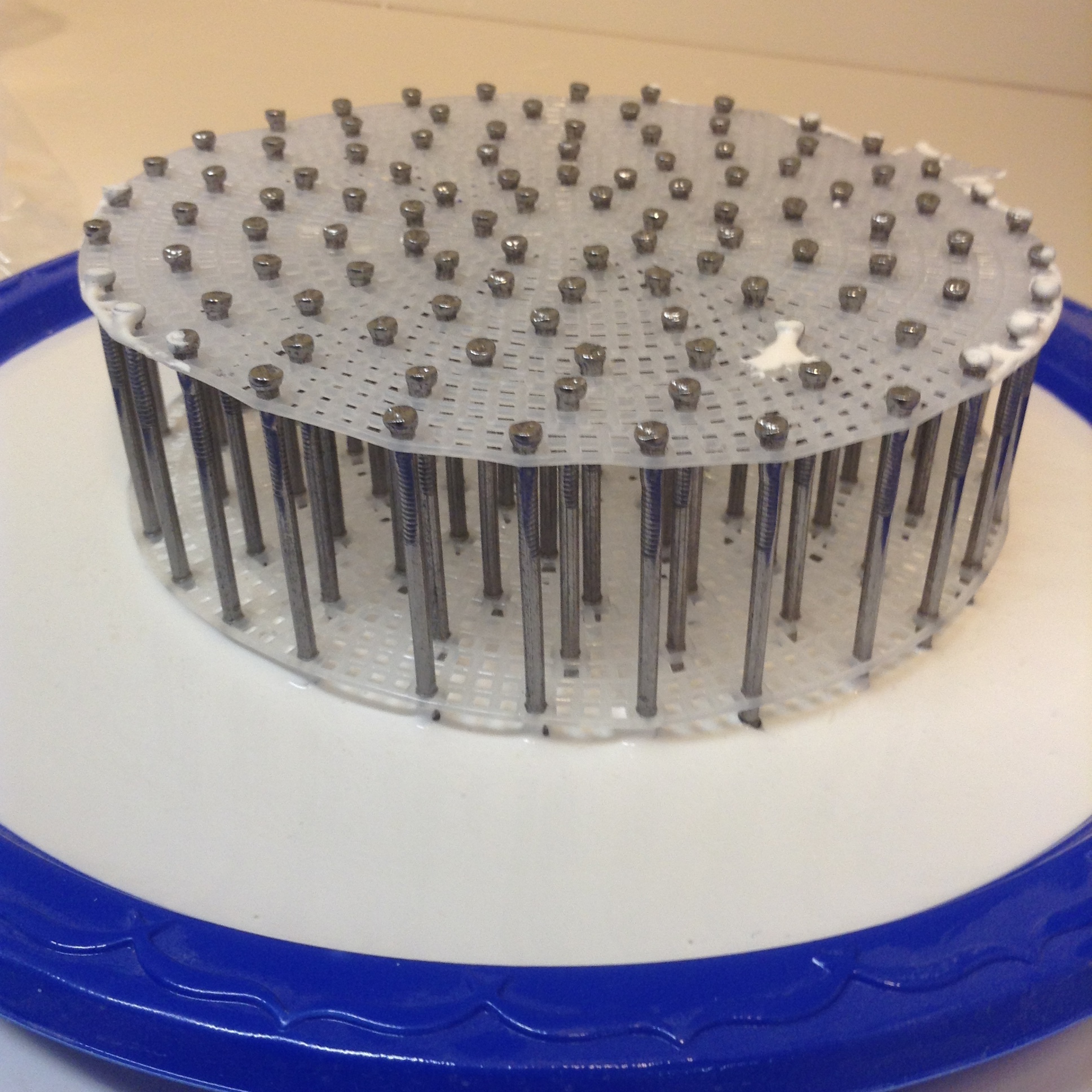

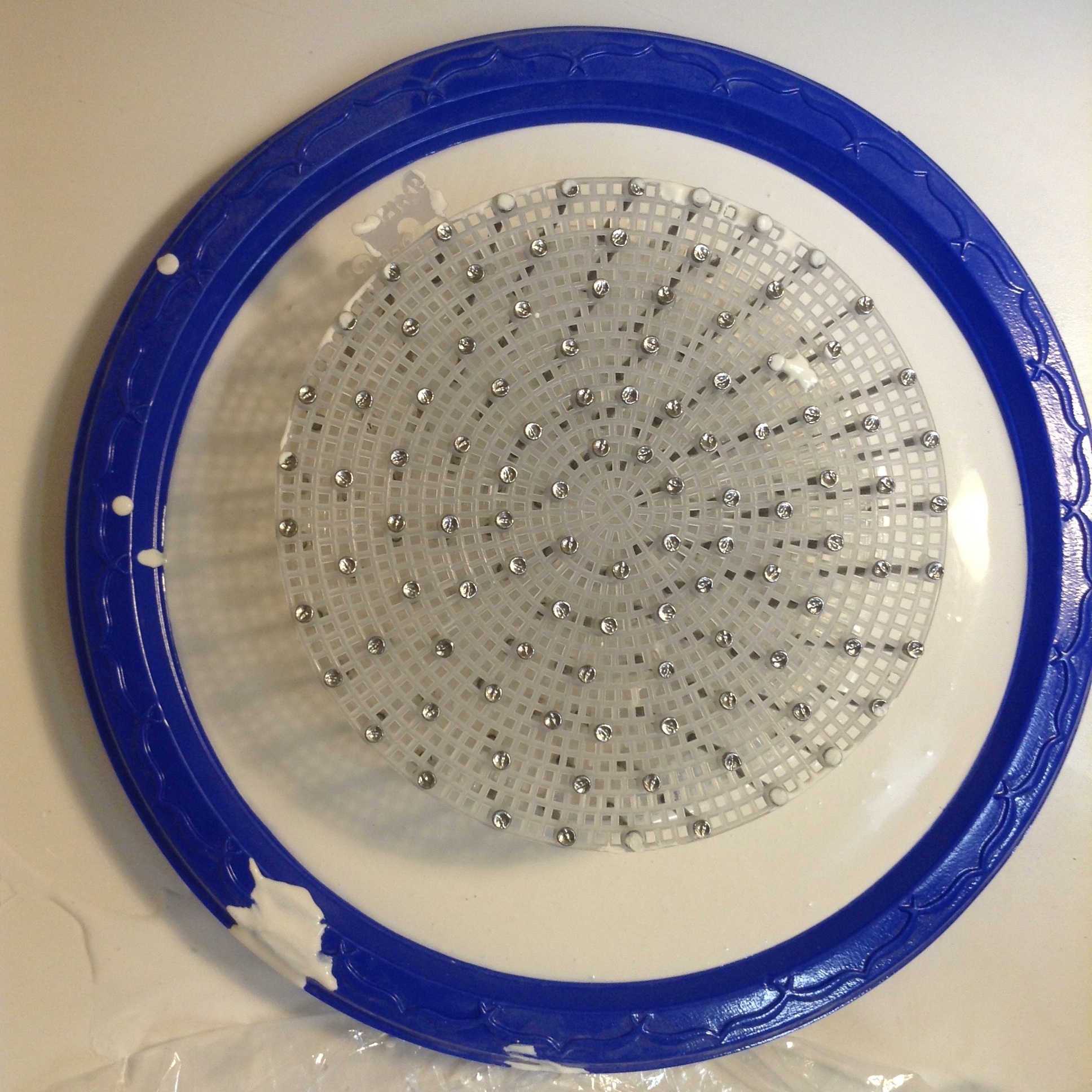

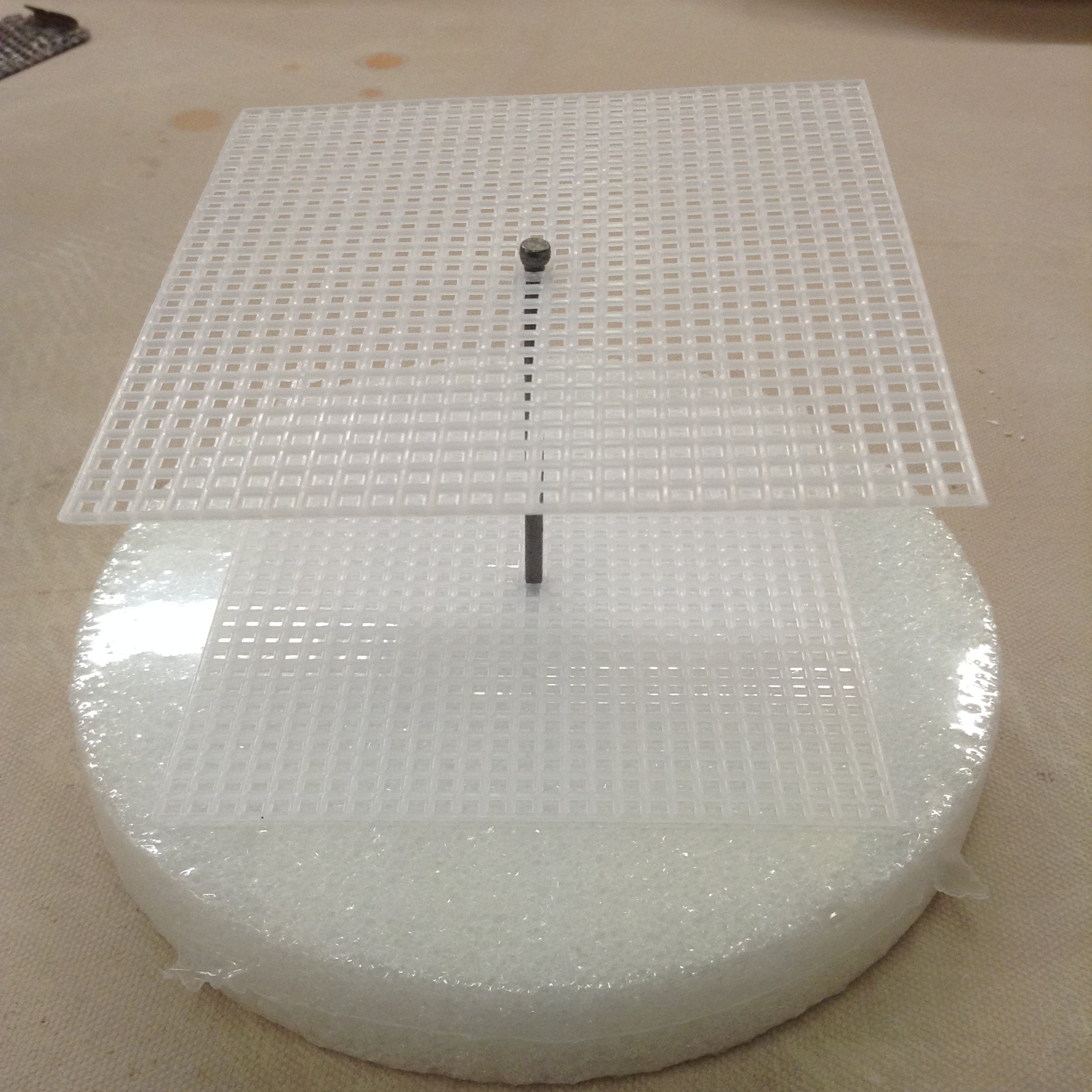

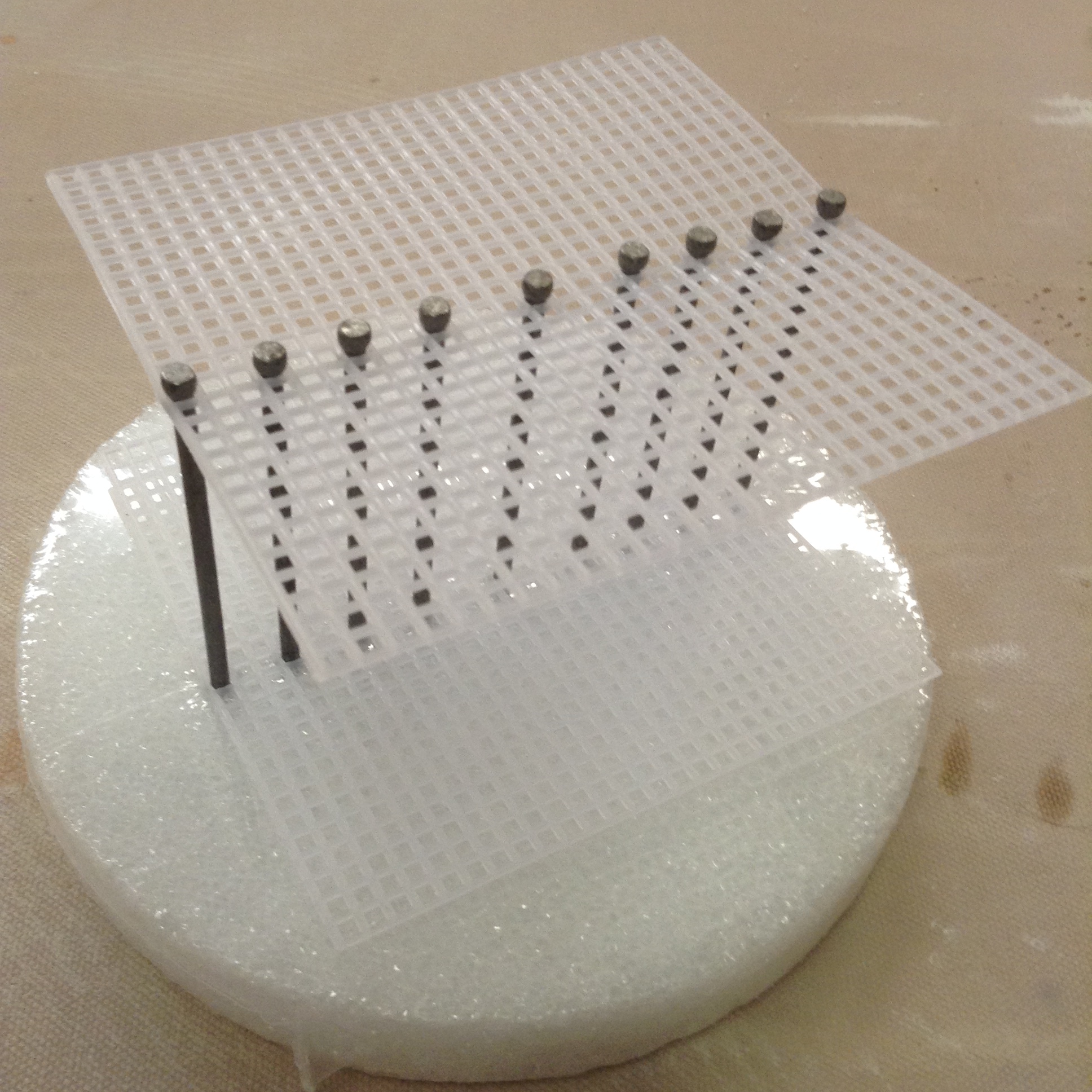

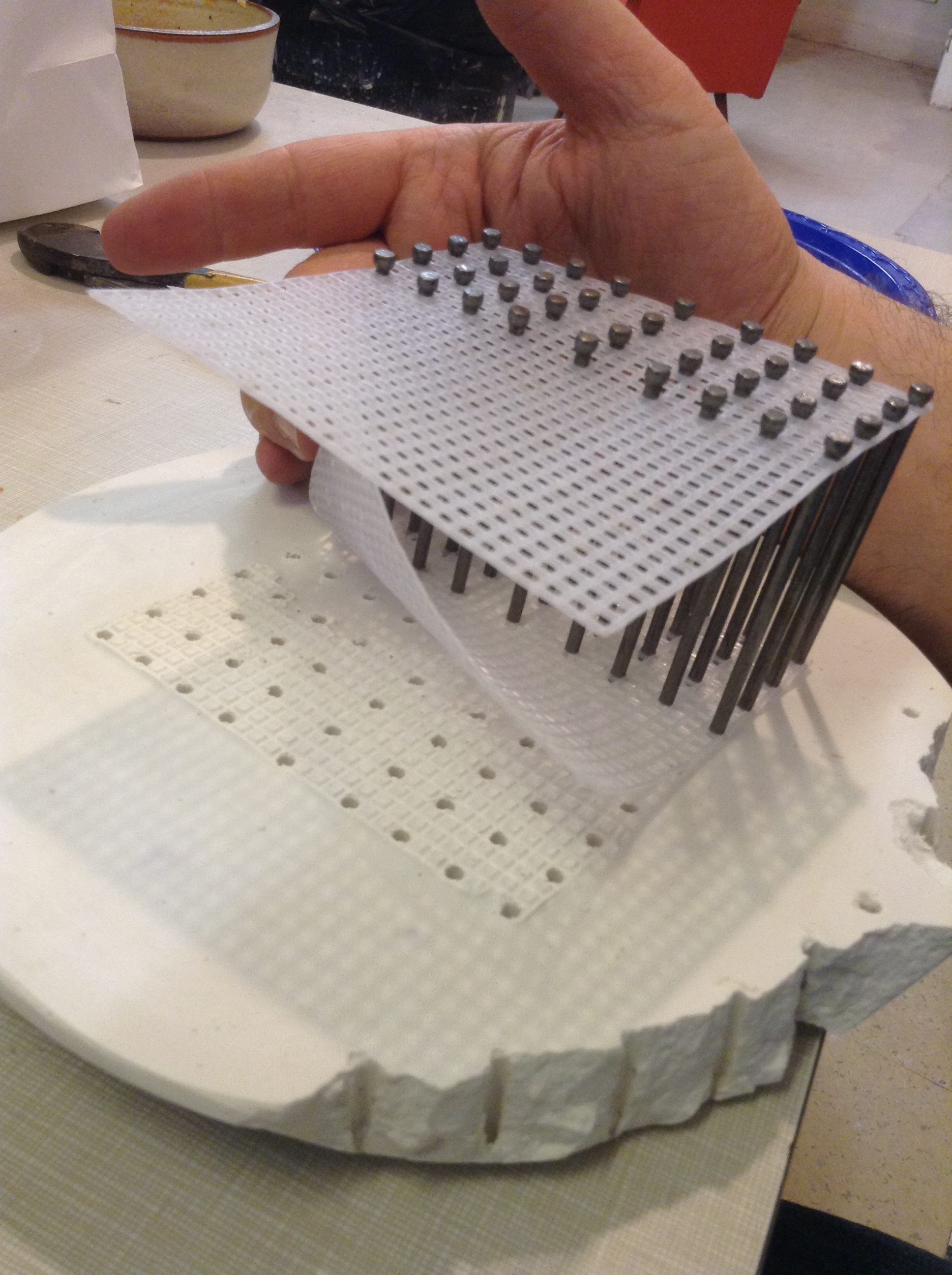

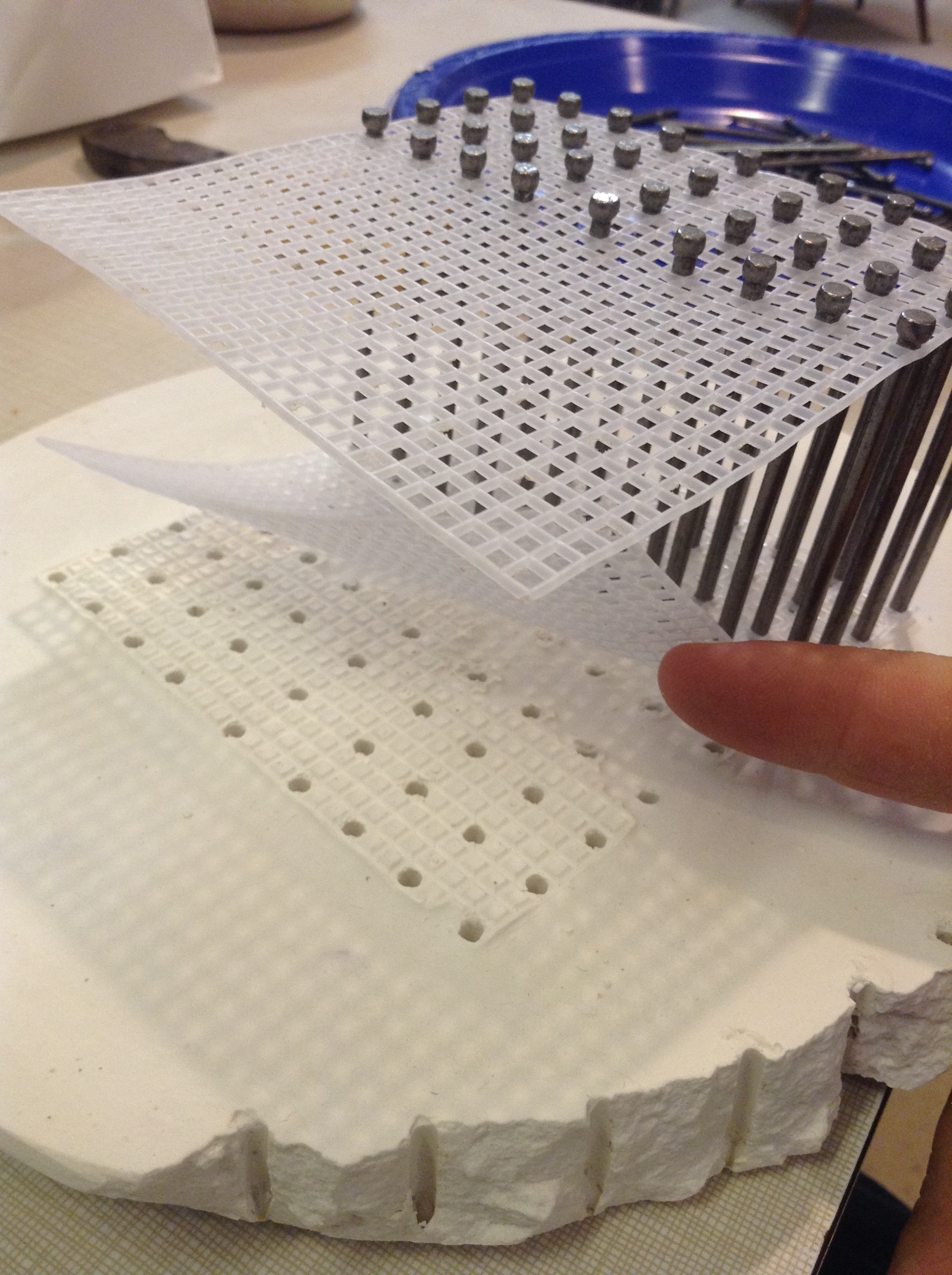

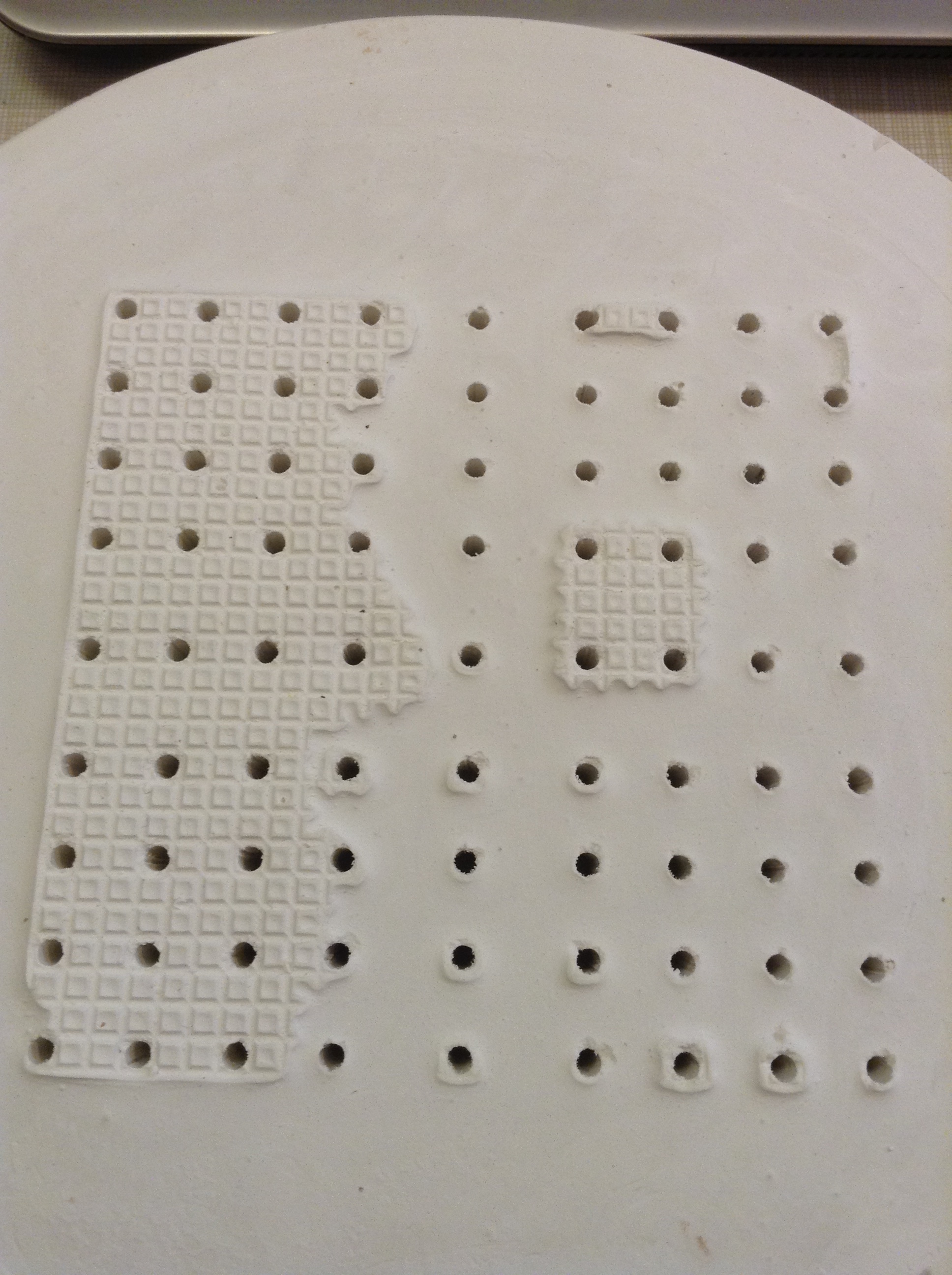

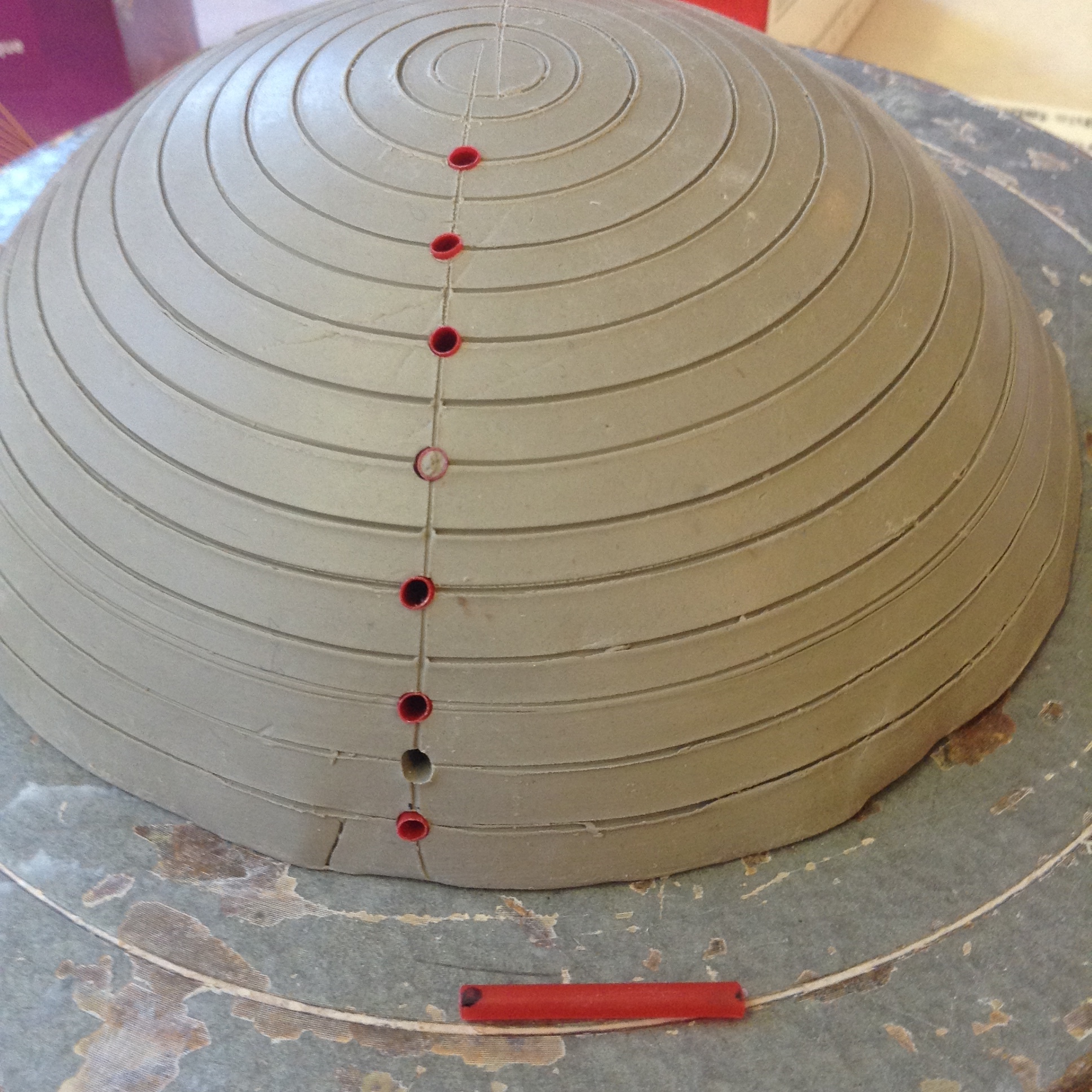

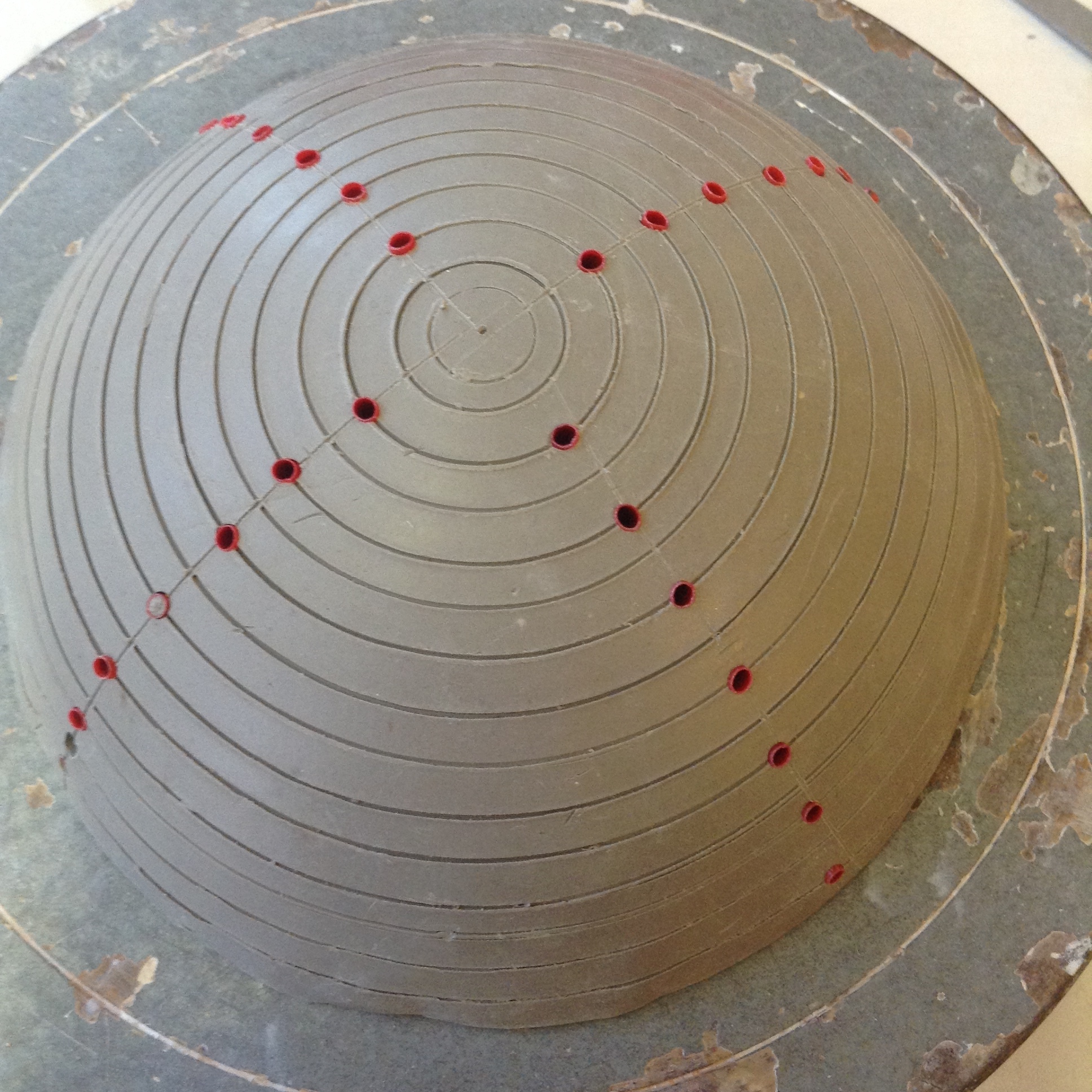

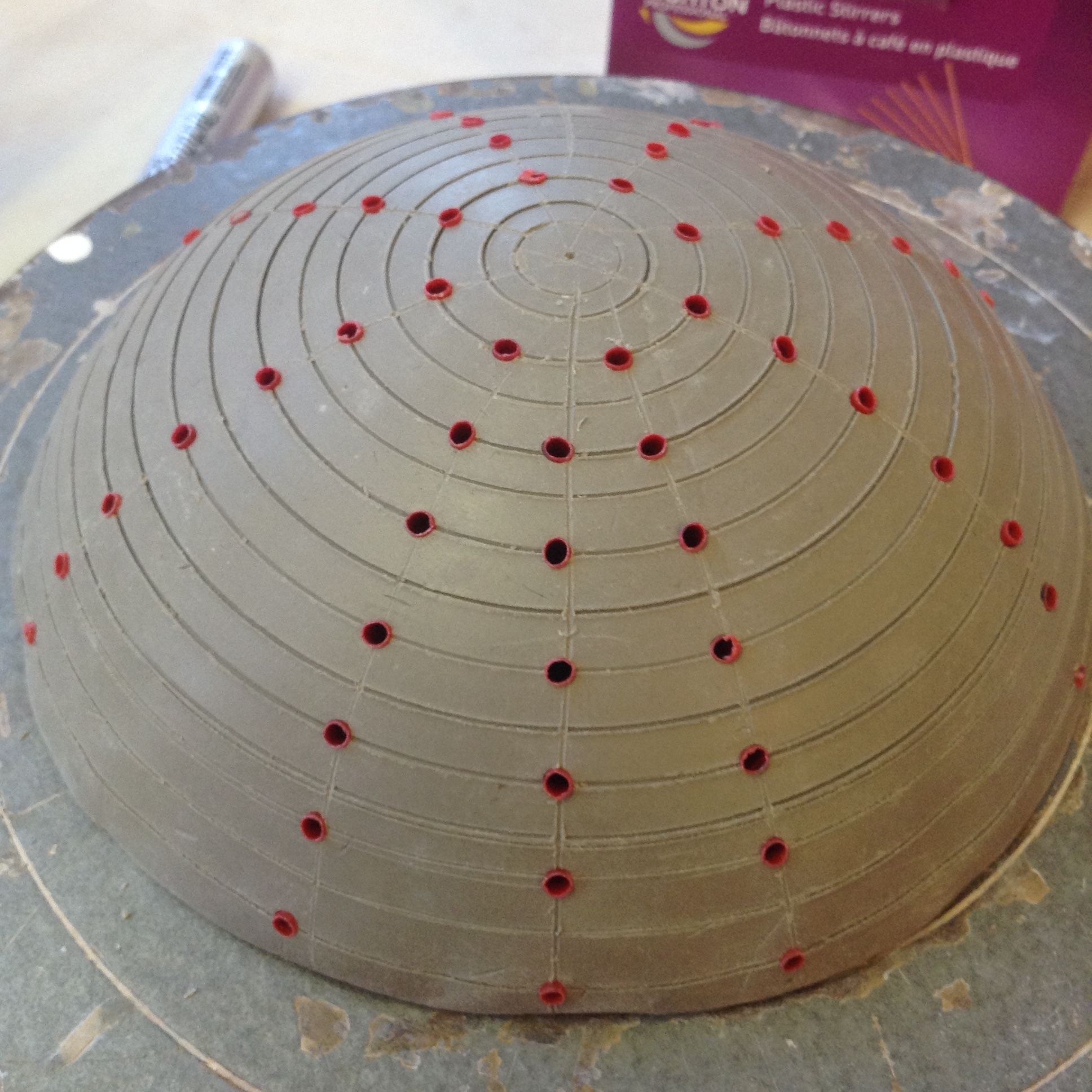

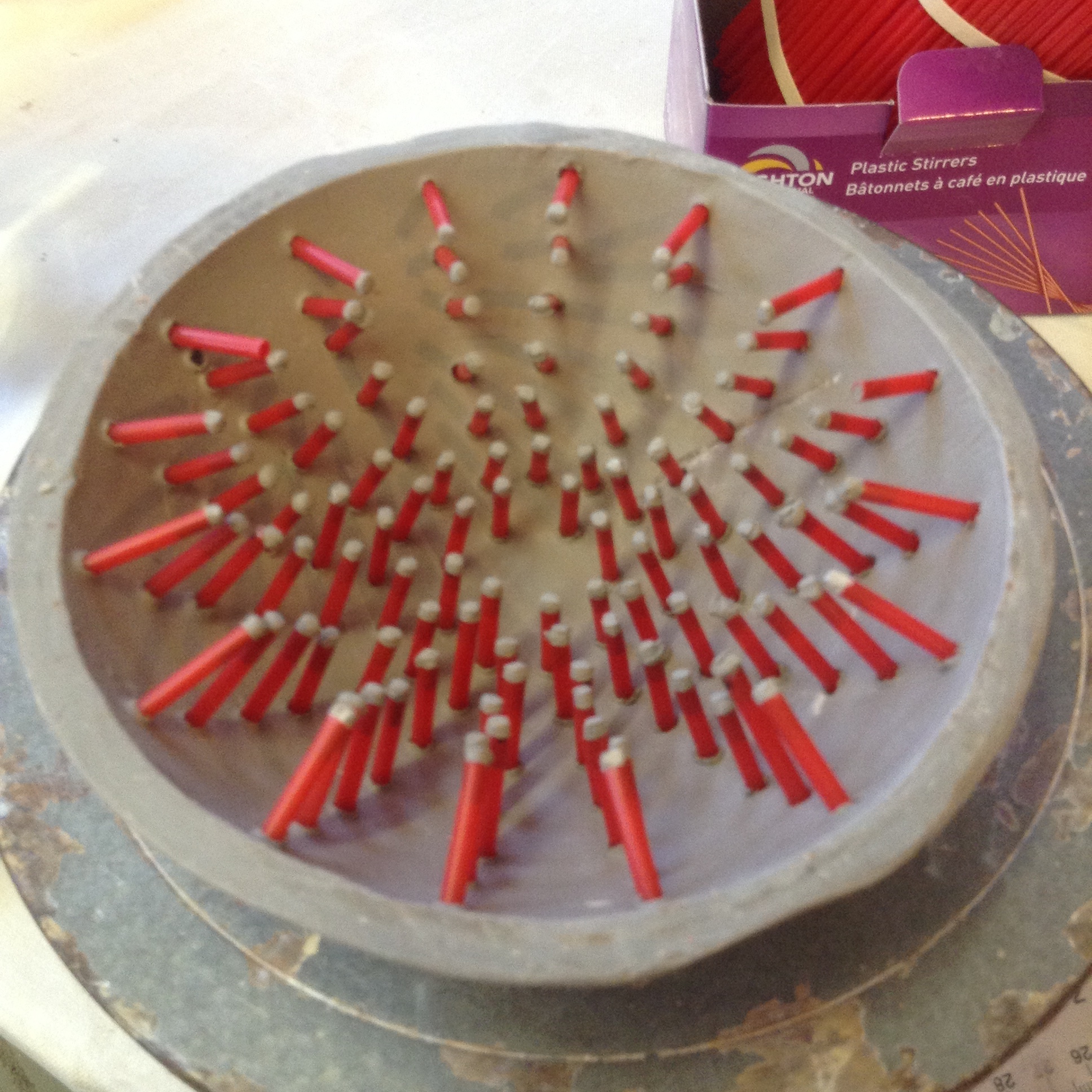

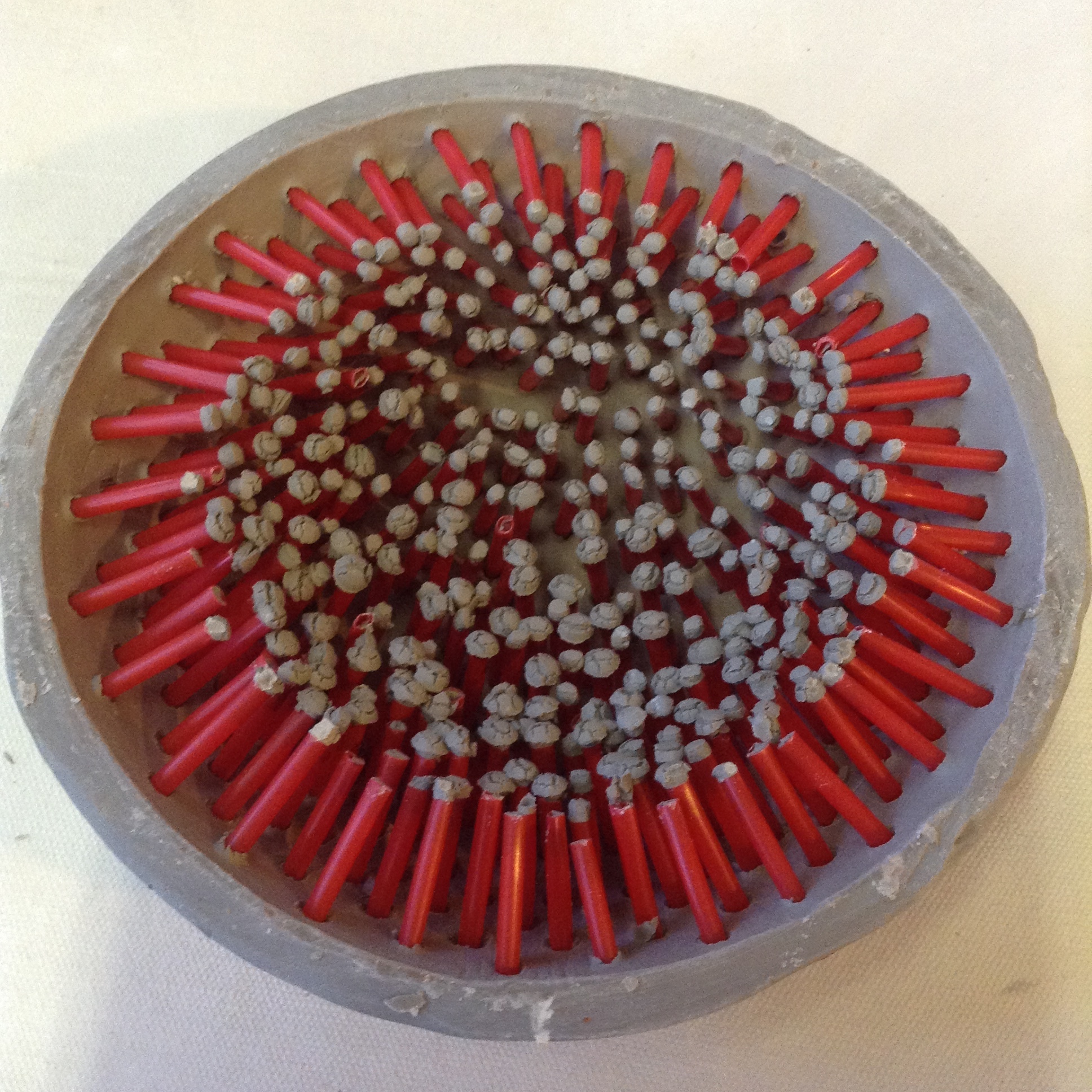

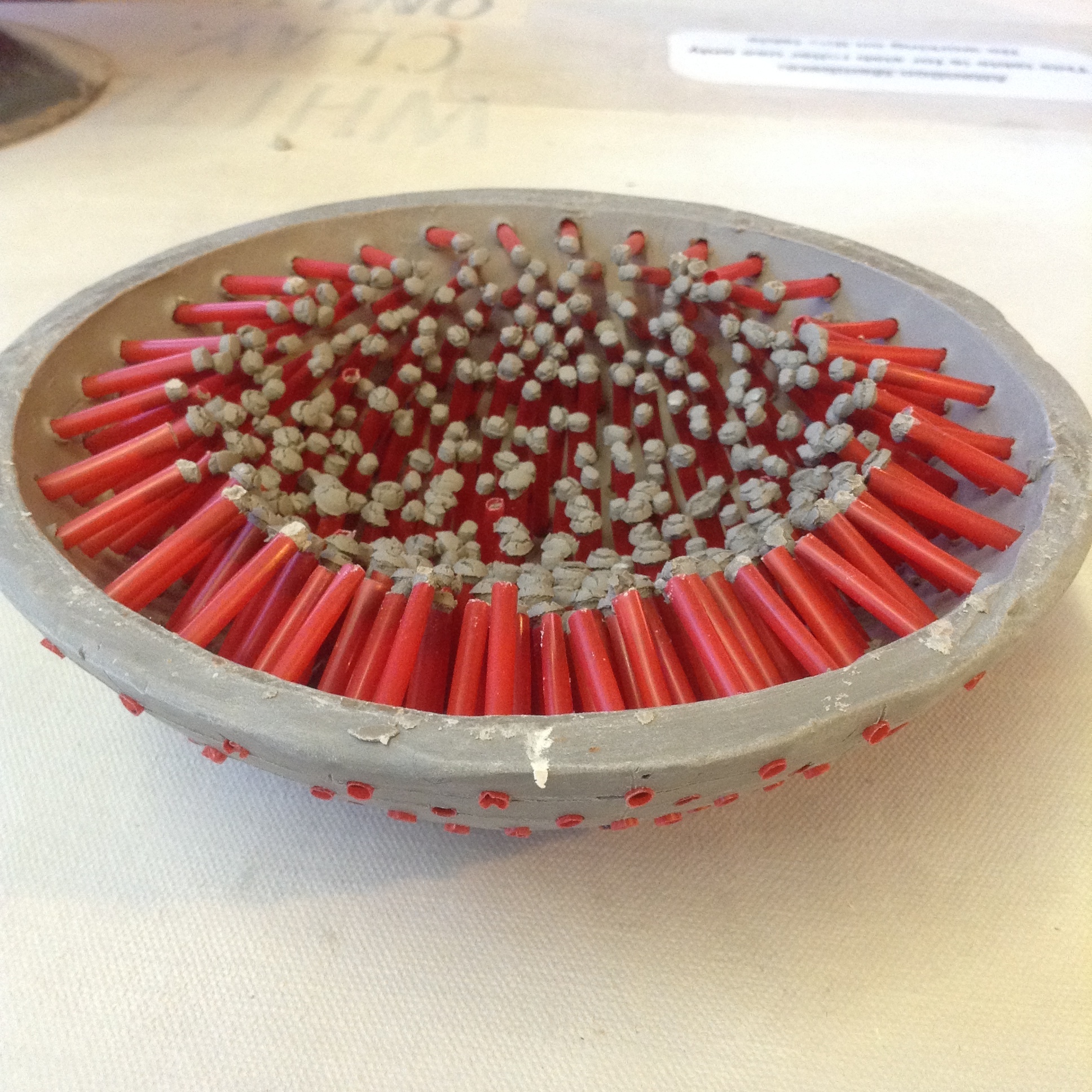

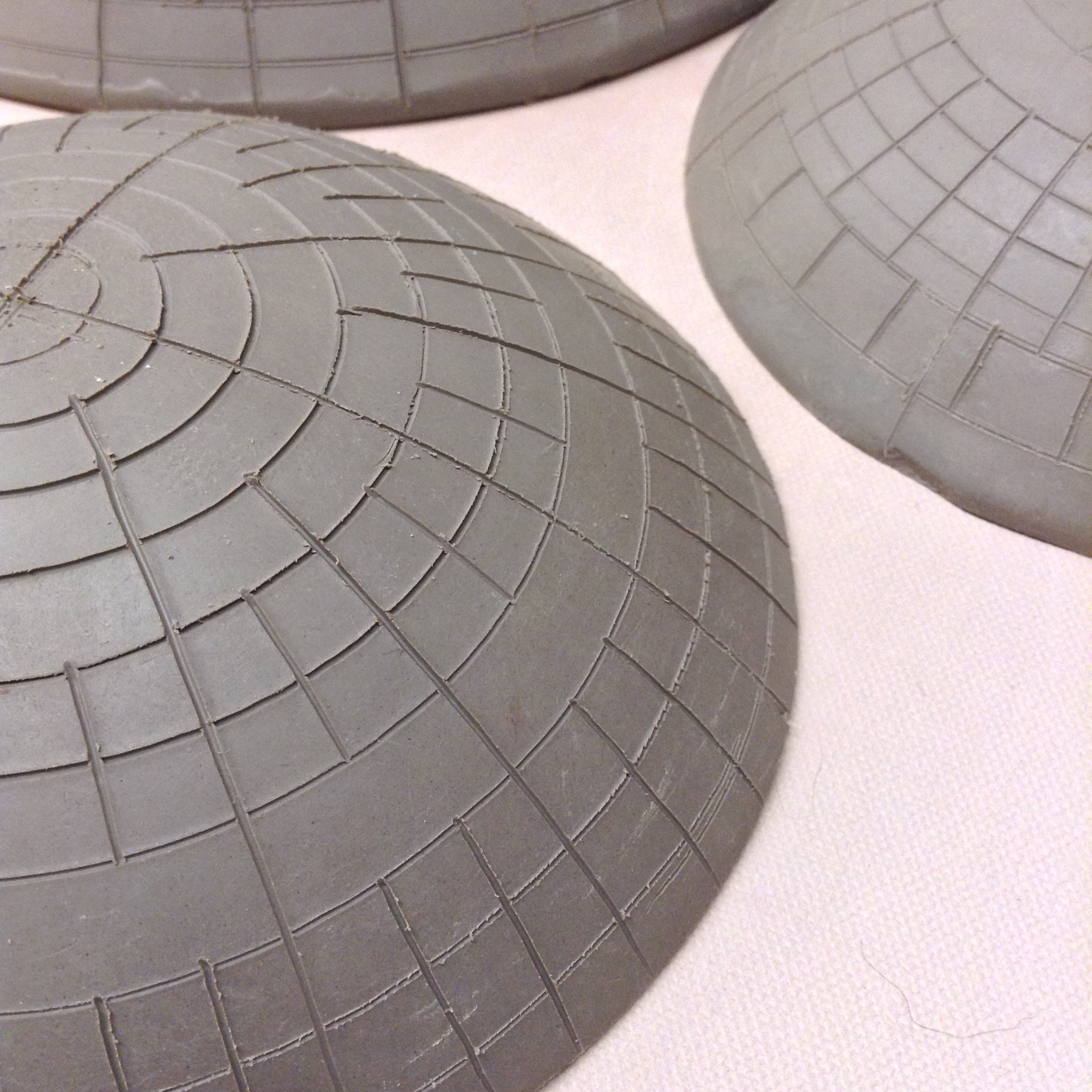

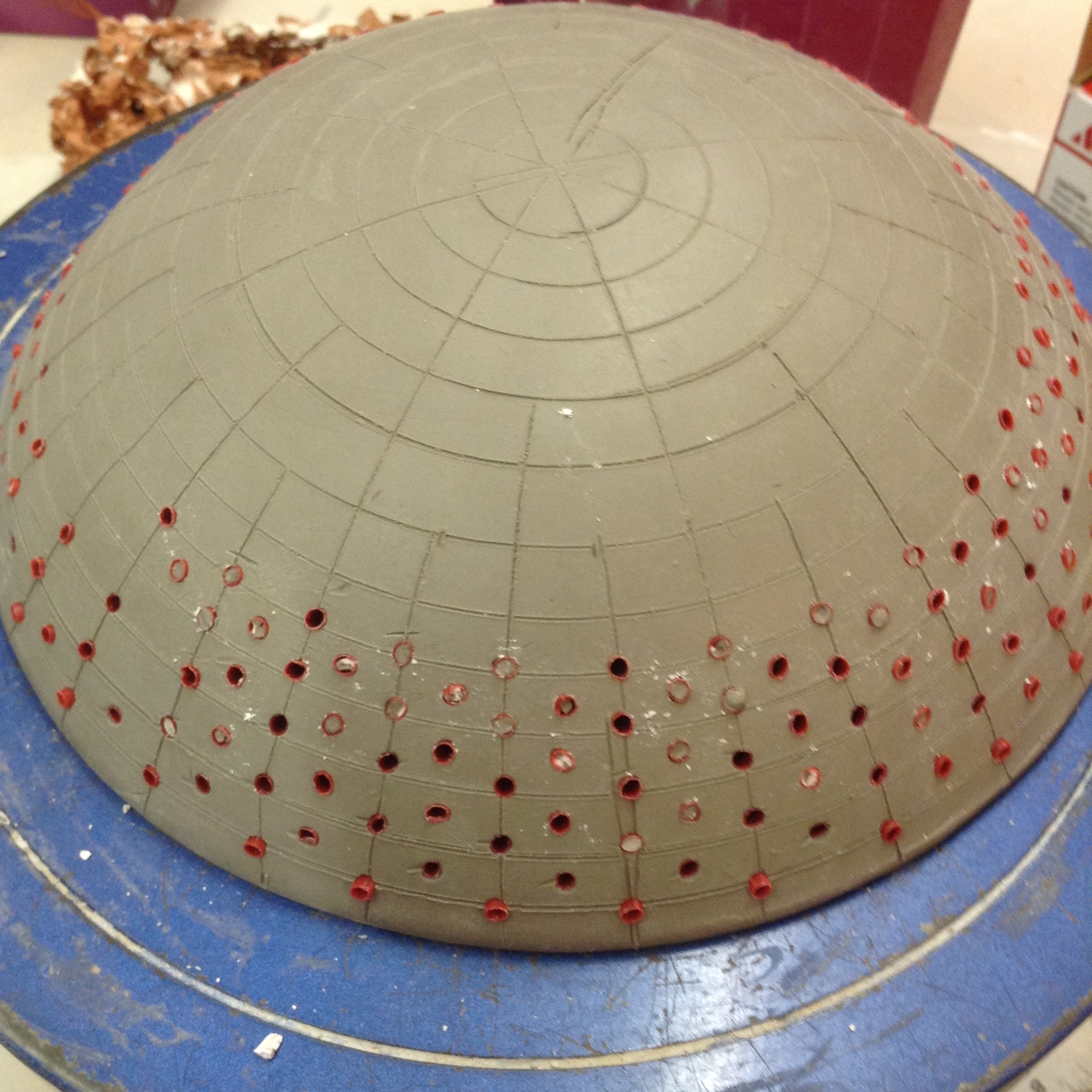

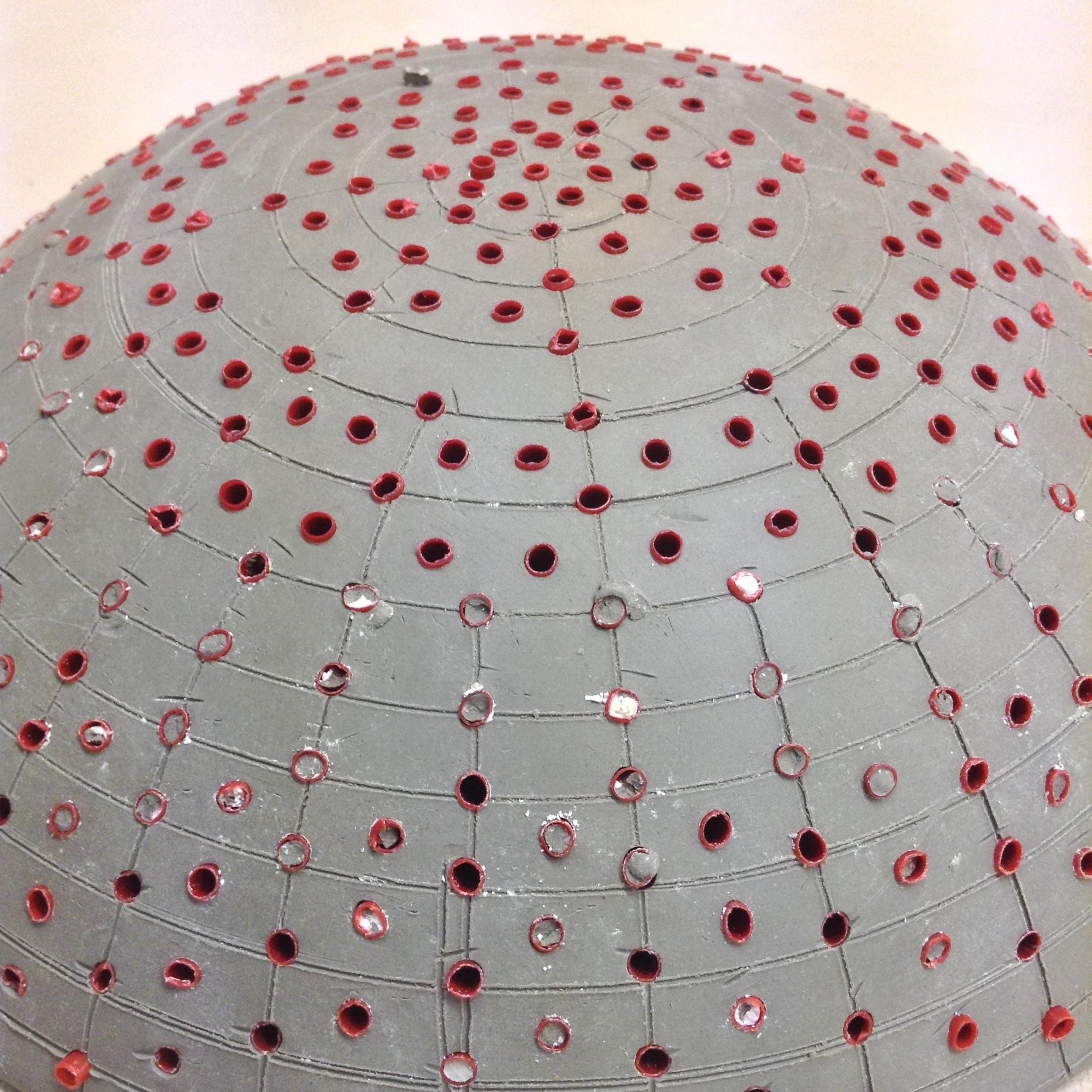

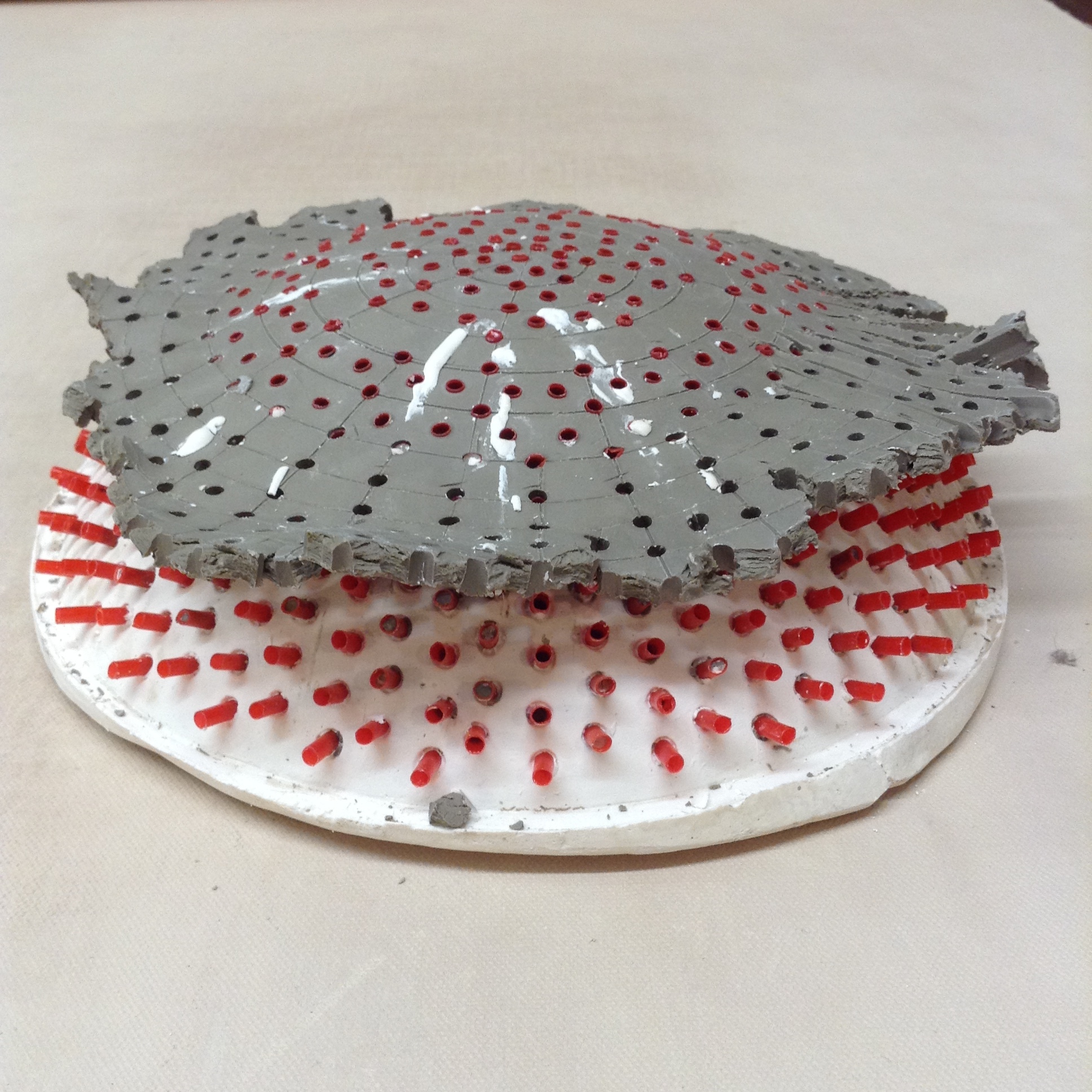

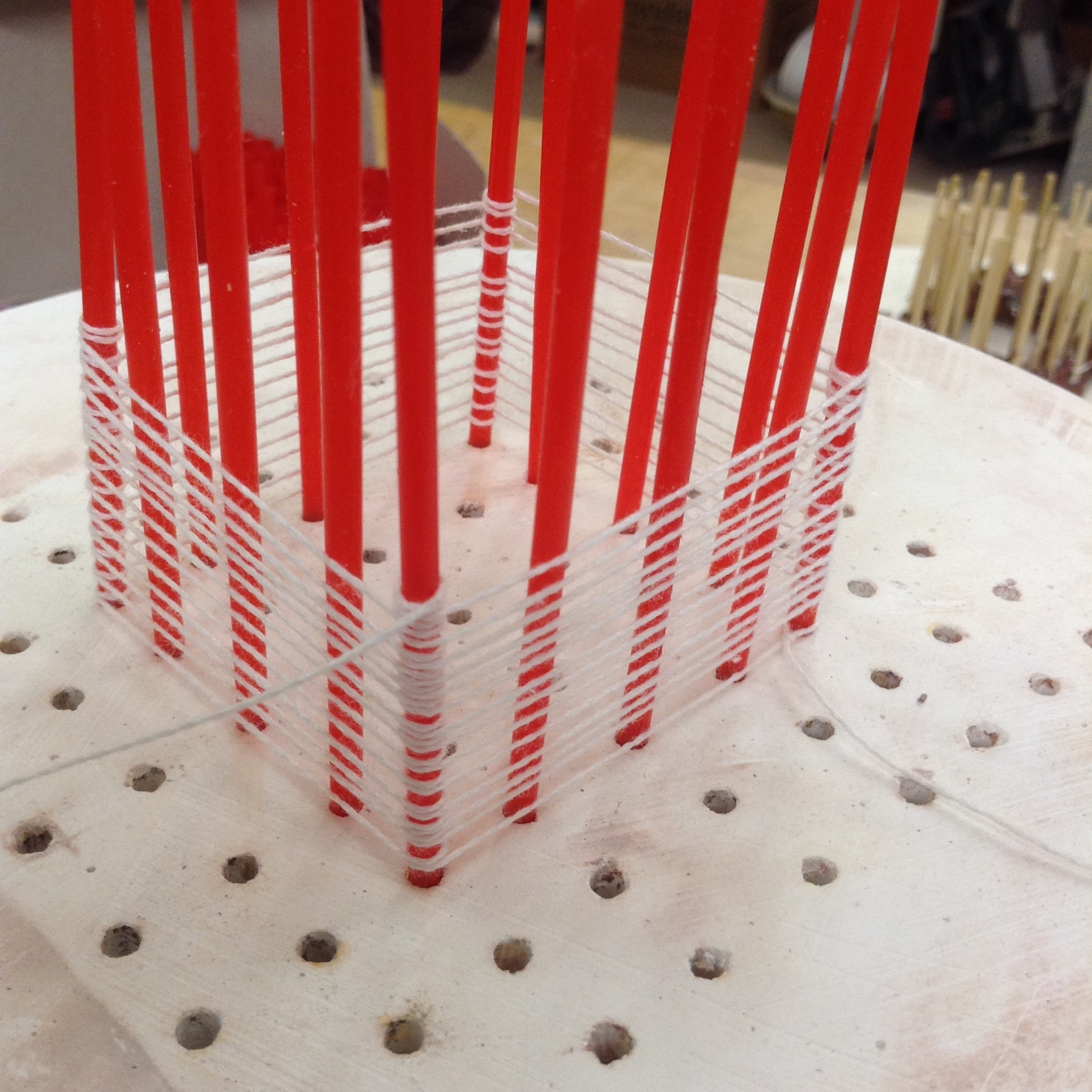

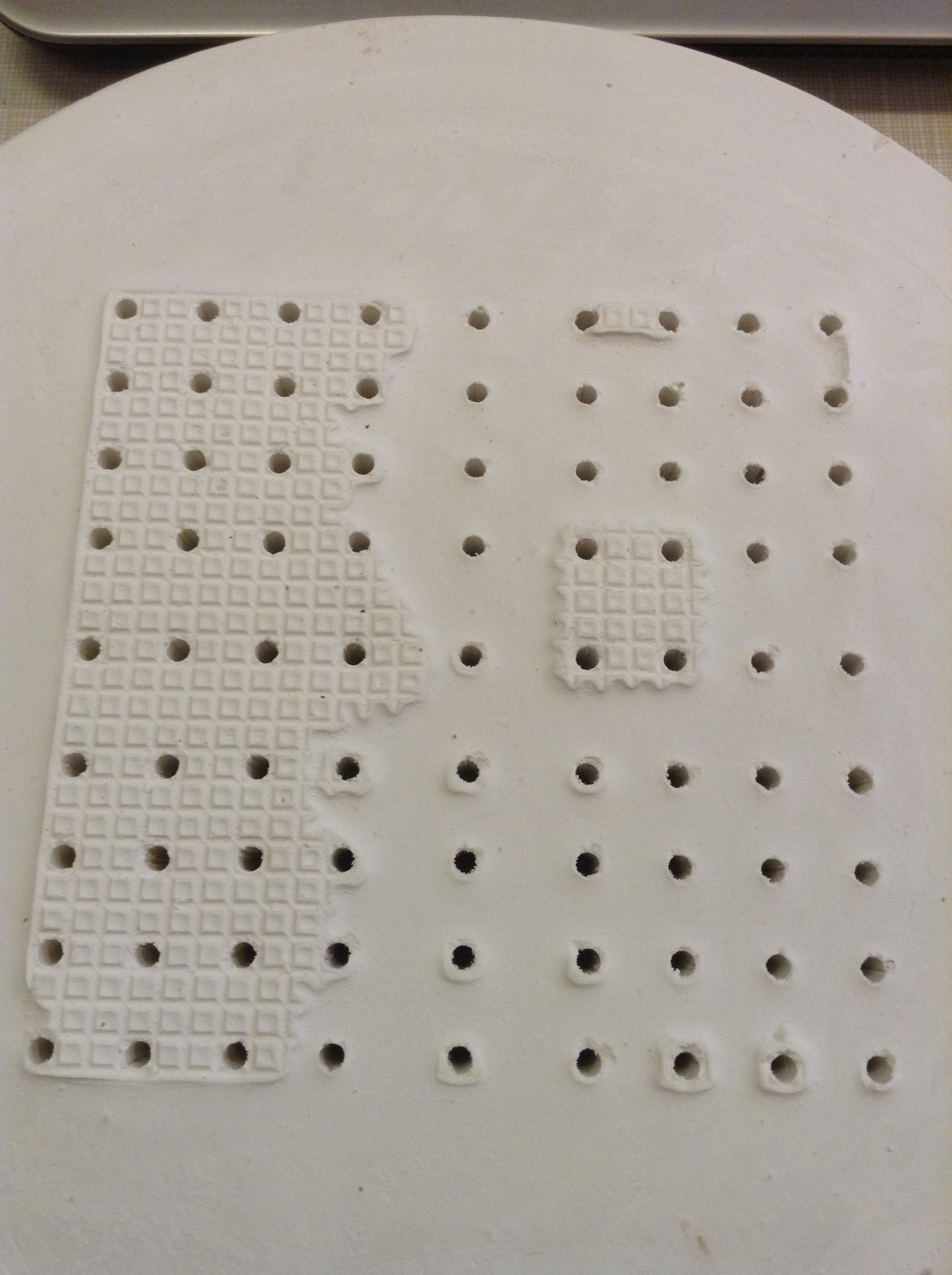

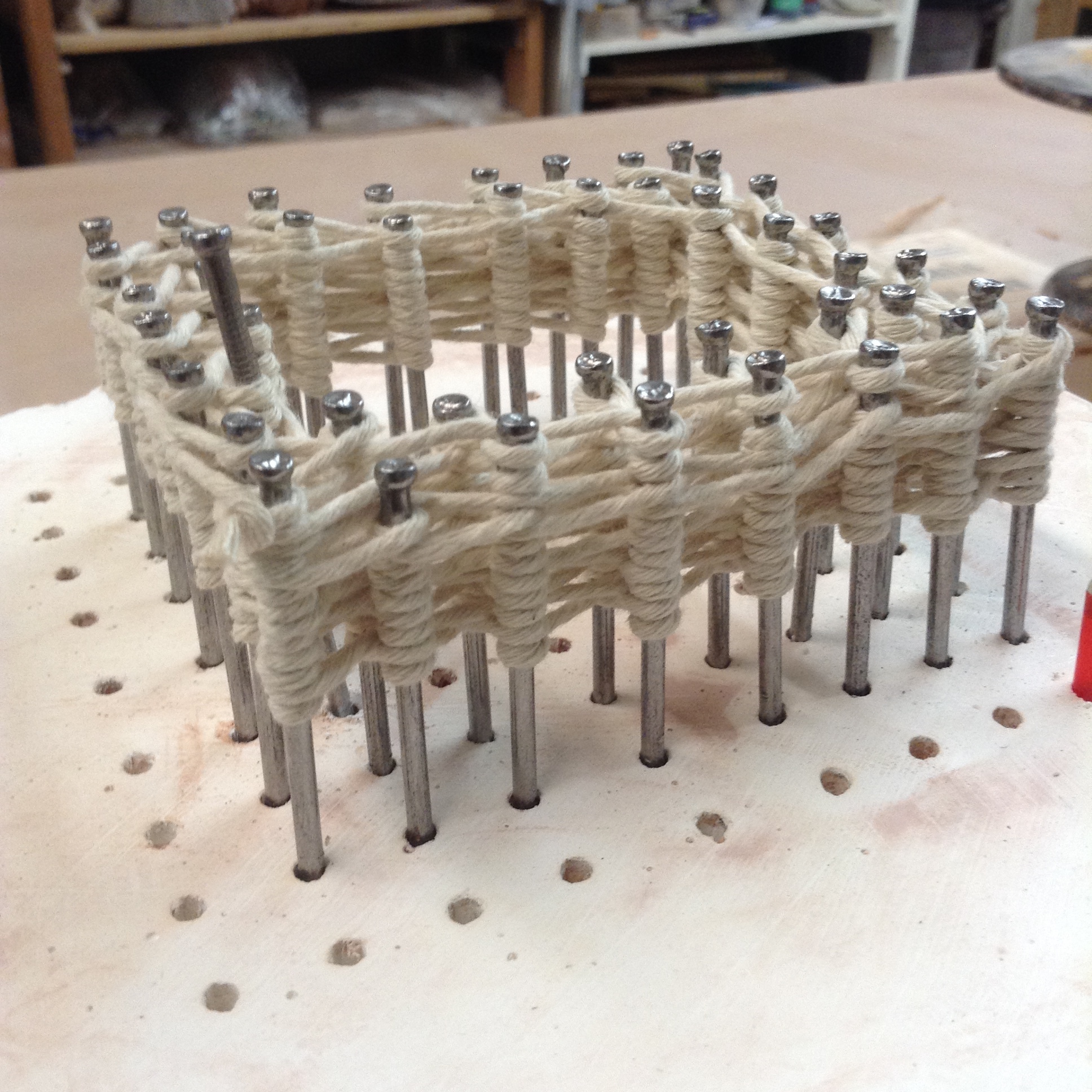

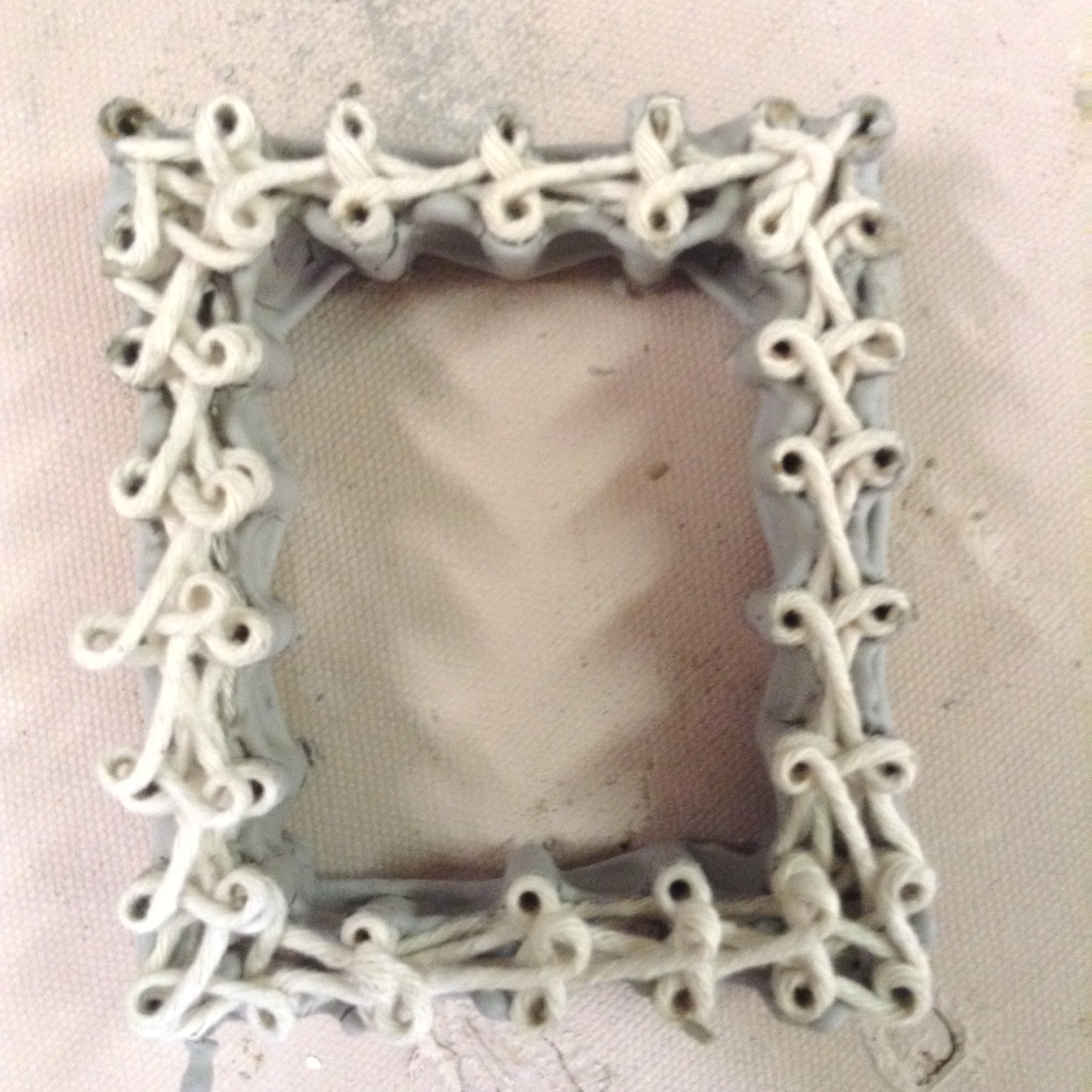

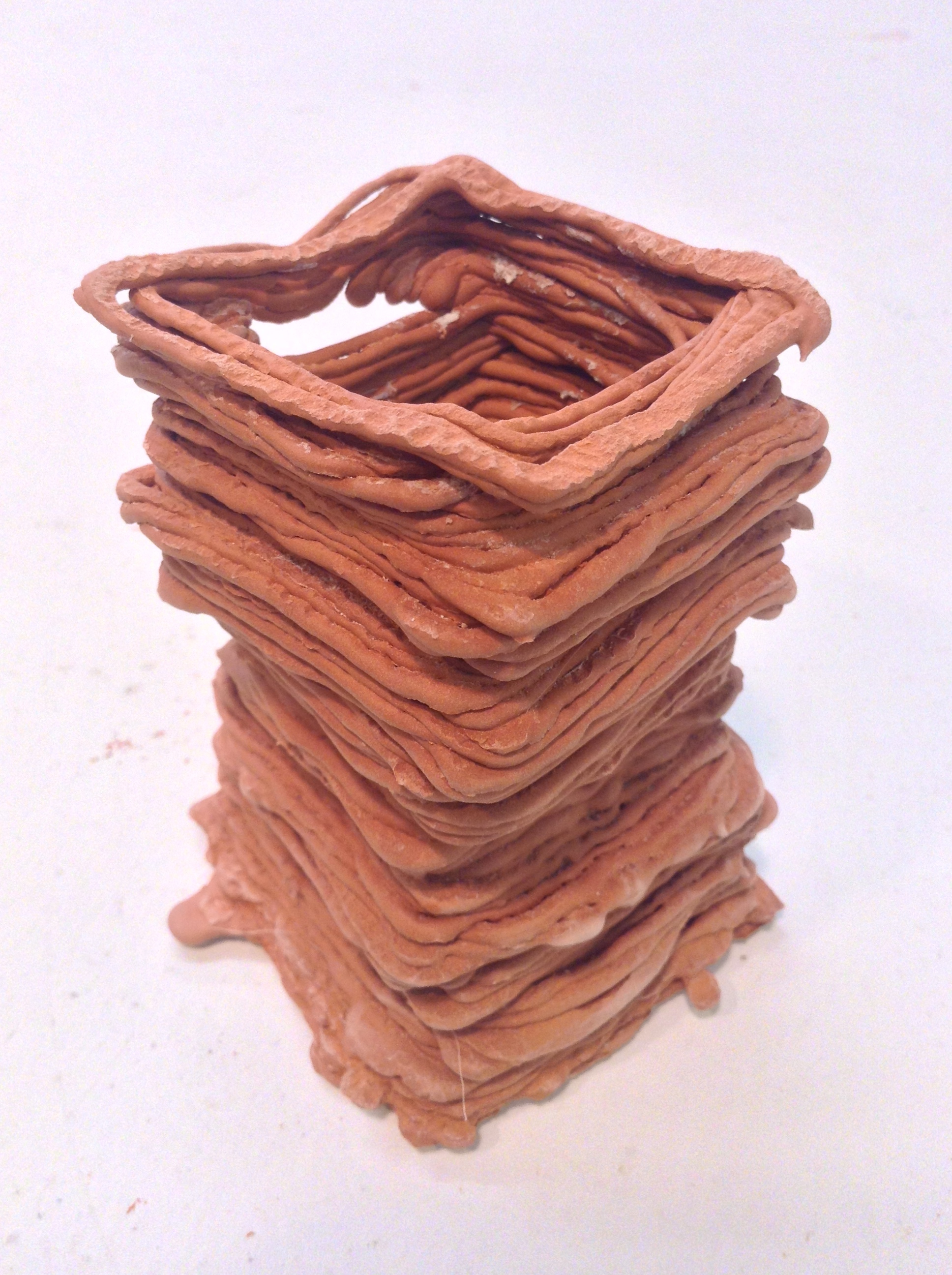

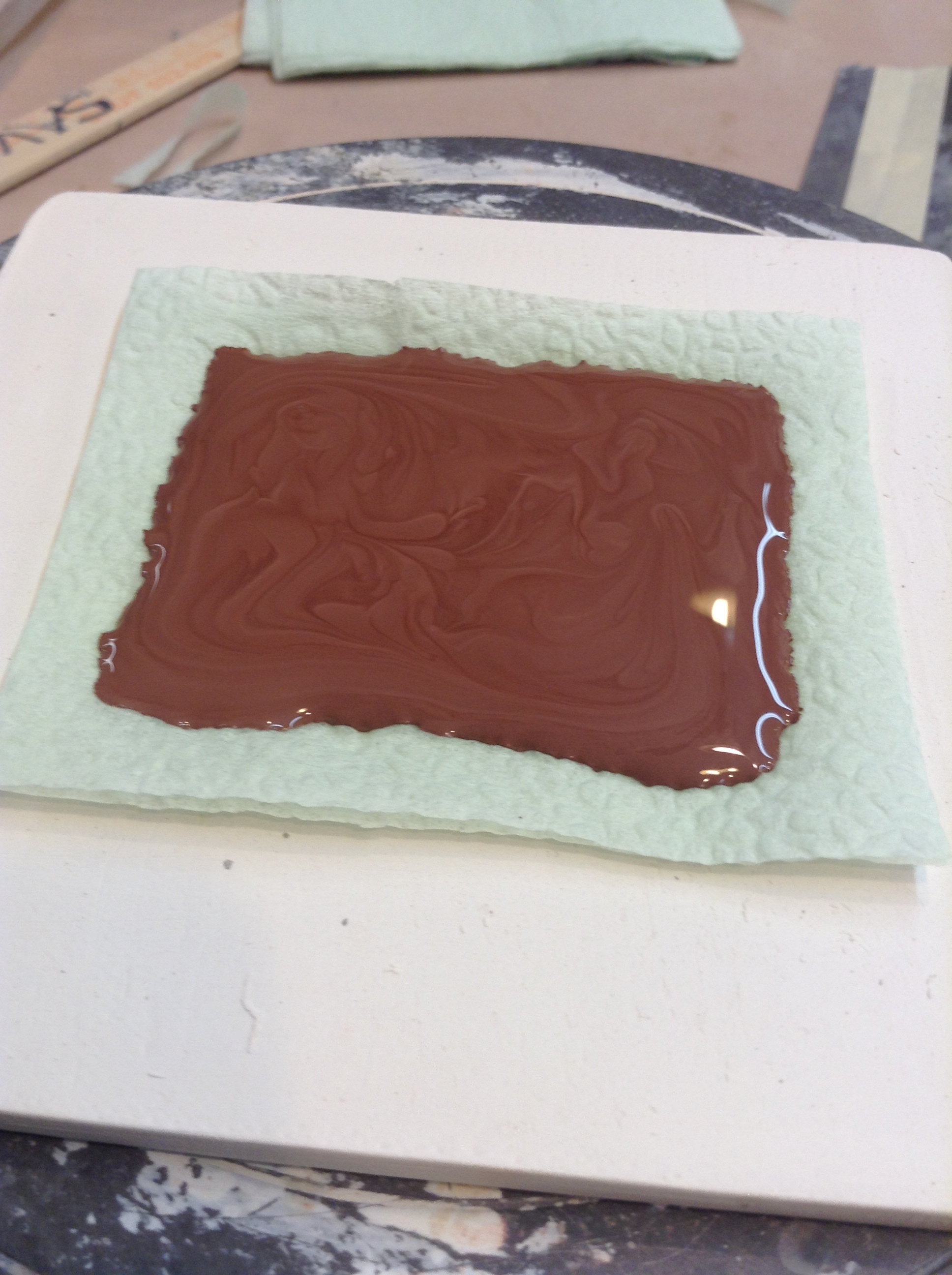

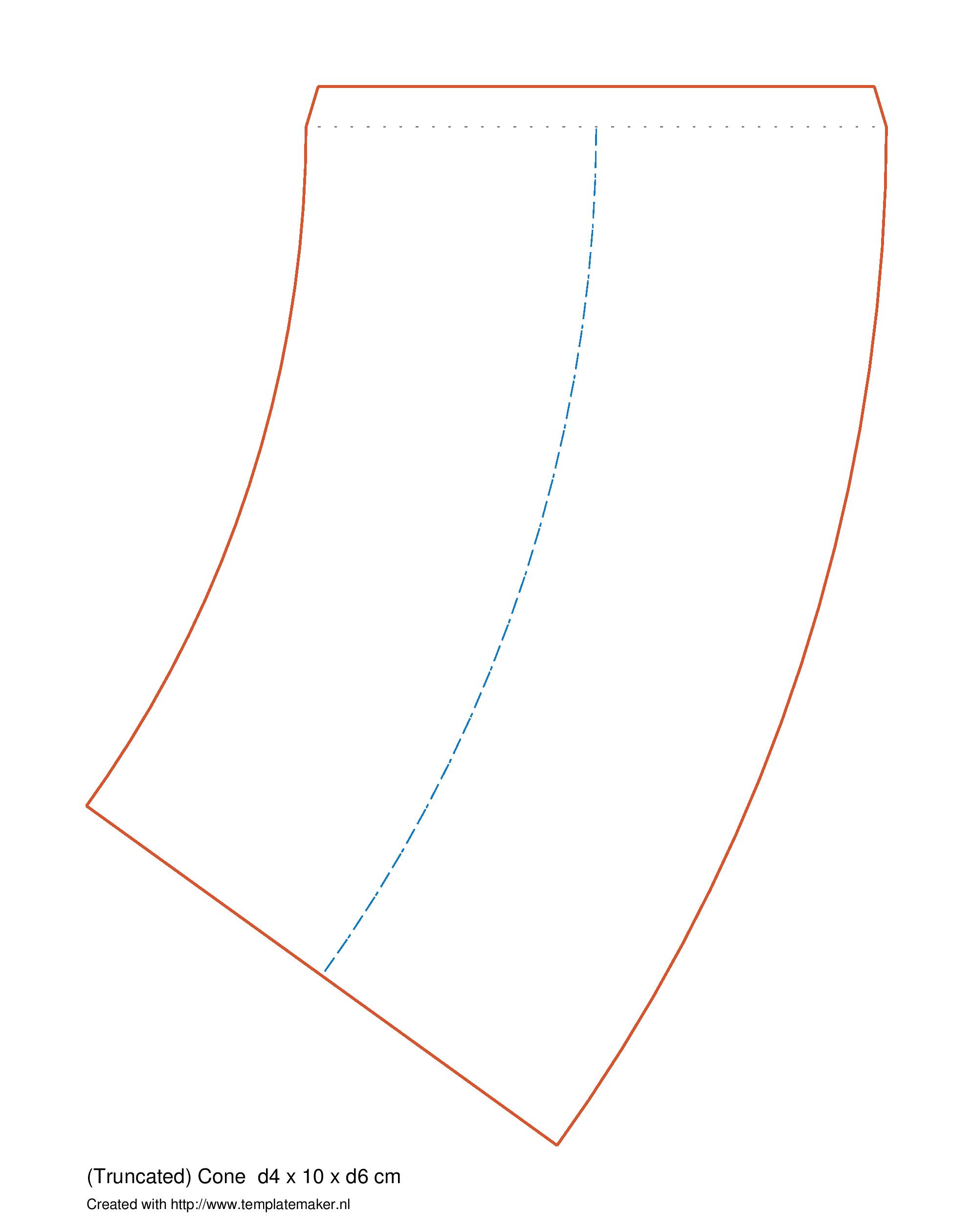

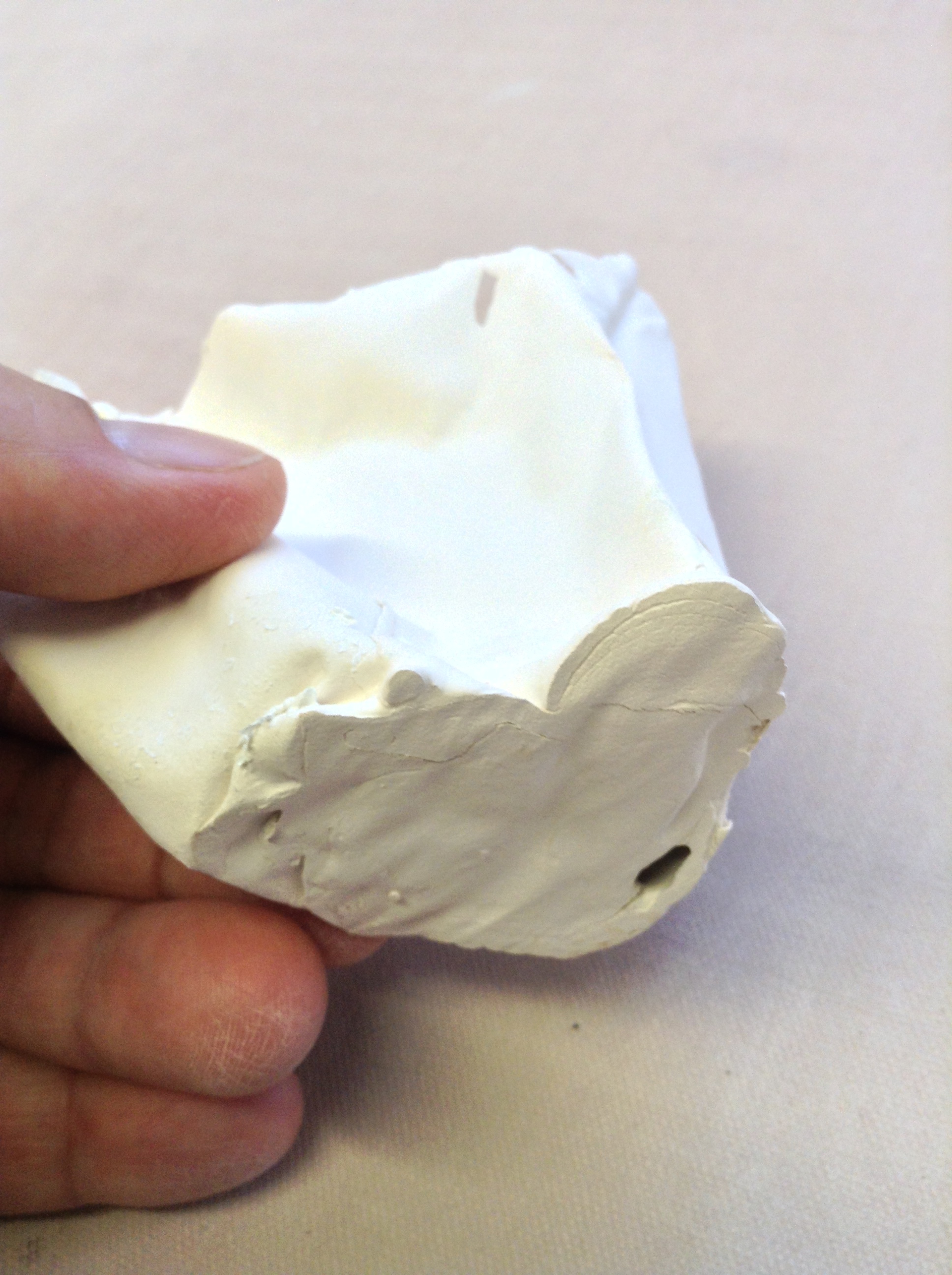

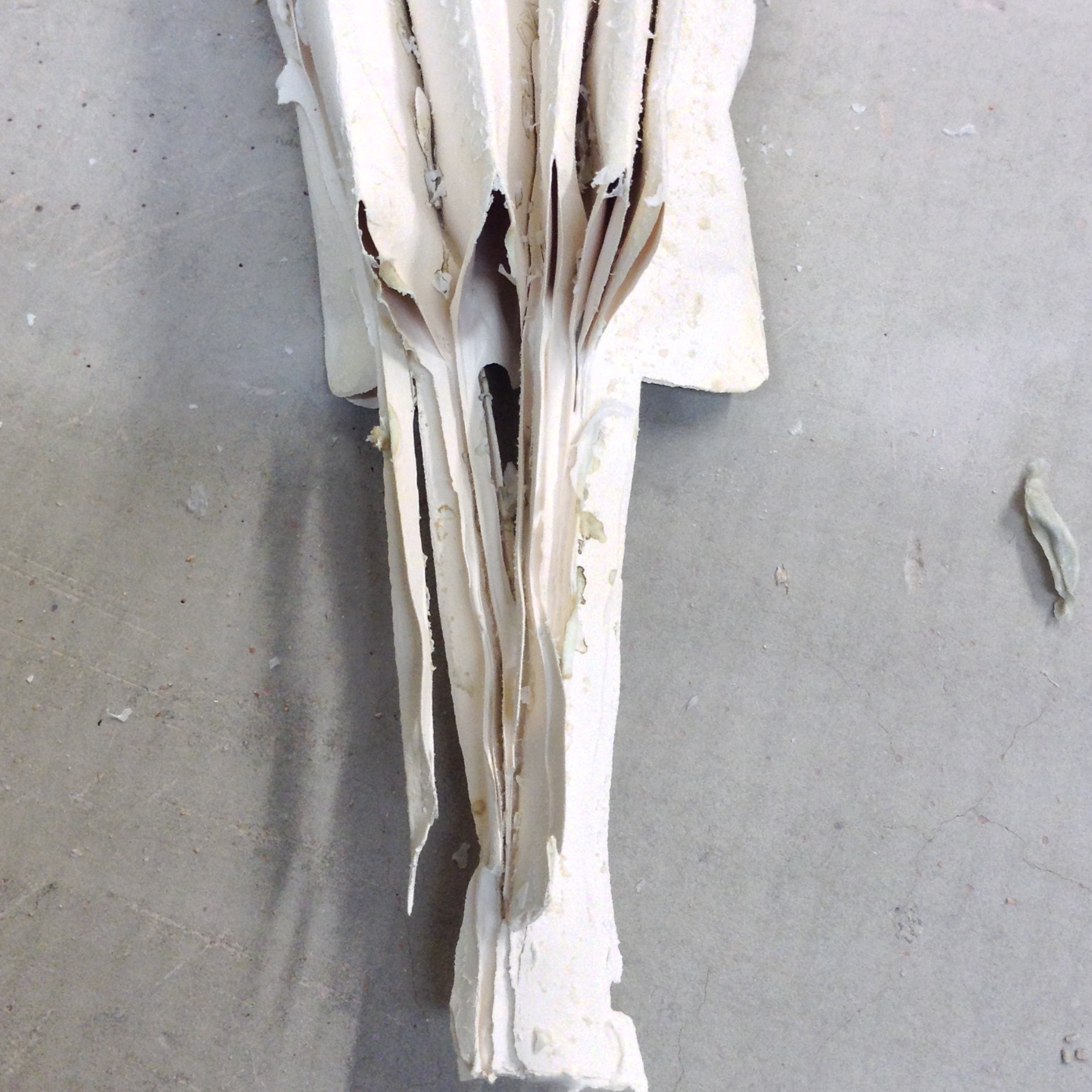

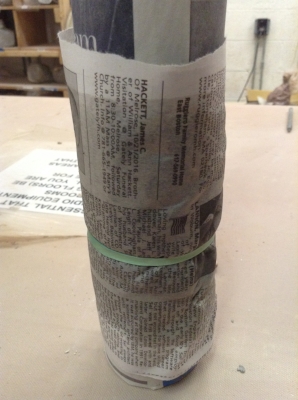

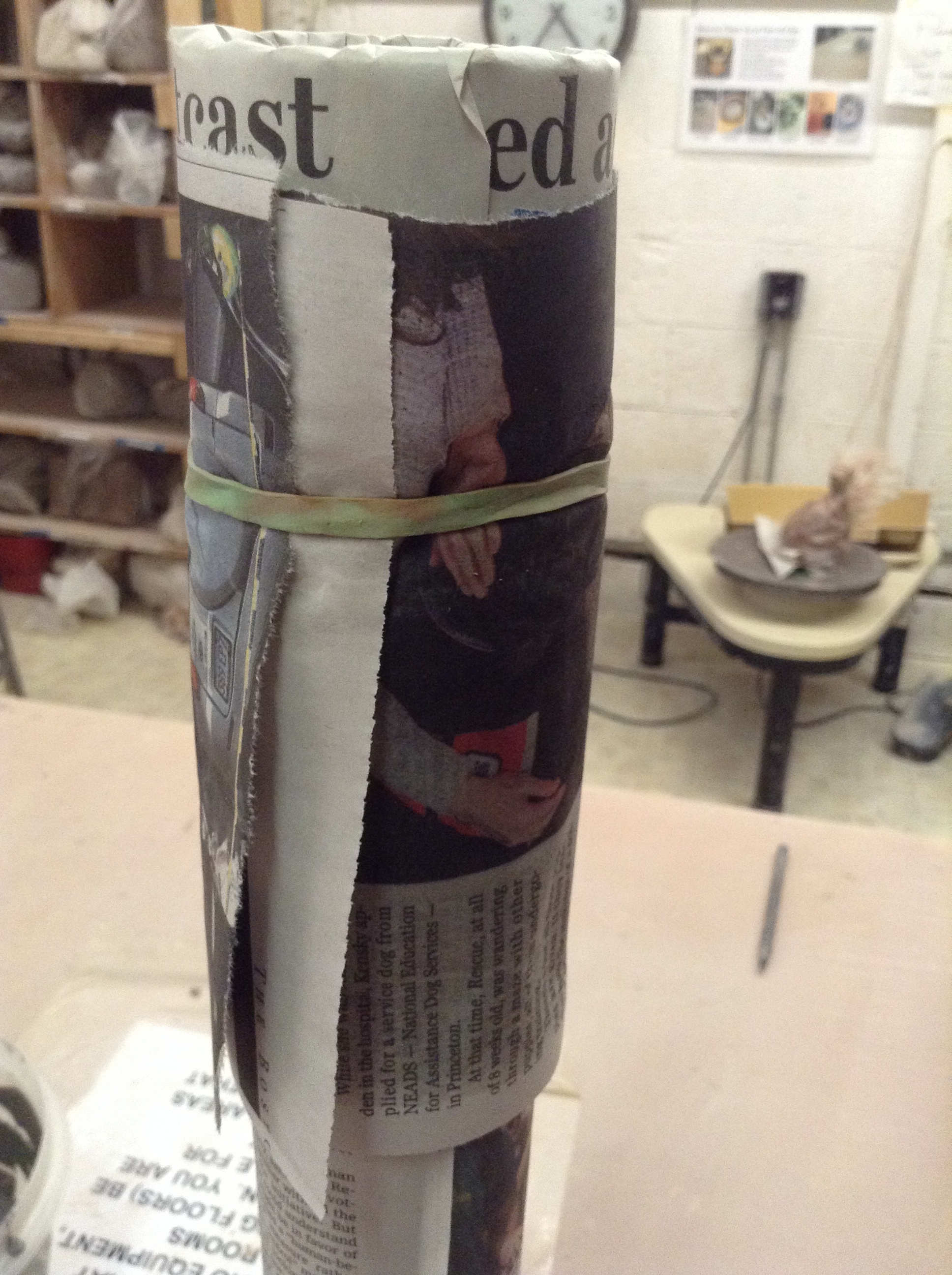

From and engineering and artistic perspective, there's already a great deal of work using liquid slip as casting material and thicker slip as a drawing medium. To add to that body of work, I'm using paper as non-typical shaping methods for the thickest versions of the slip recipes. Using this paper-clay-paper laminate, I'm exploring the methods needed to make functional pieces or sculptural objects in ways that could scale up to many dozens of pieces. Plus, it's fun and the resulting forms happen fast. These methods have the incremental-slice methodology of digital 3D printing, but also retain some of the analog hand variations possible with sculpting. Since it's a mix of processes, at the moment I'm calling it "hand-printing."

From a visceral standpoint, I do wonder if something is missing from the process when we don't touch clay directly. Touching the familiar form of clay holds a great satisfaction for so many people. Soft clay seems to invite the most direct approach of the hand, and records all actions upon it. We make our mark on the blended, soft and moldable stuff from store-bought bags. We wrestle and thrash with the hard-won, rocky, grainy, often sticky piles of it found outdoors near bodies of water. Is there anyone who hasn't touched clay at some point?

But, that said, for those of us who are as likely to draw as sculpt, or build instead of sculpt, what can clay do? Maybe something like these things I'm exploring here.

THE SKY'S THE LIMIT.... ALMOST

What's next?

- Larger abstract forms with more than one interior wall

- Changing the orientation of the growing pile so that the layer direction changes

- Getting significantly different diameter nozzles, so that a layer might have one huge strand or several smaller strands, all combining to become the structural wall

- Pleated surfaces that are mounted in frames as wall decoration

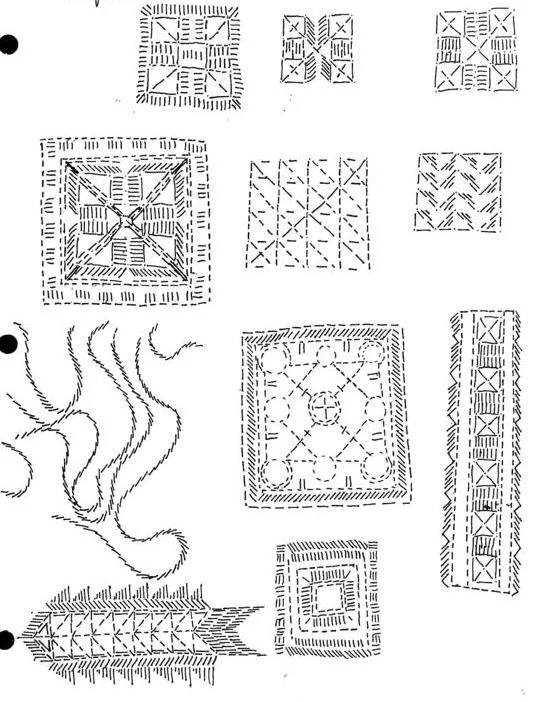

- Slip trailing as typically used for decoration printed onto newspaper just prior to spreading the thicker structural slip, so that after distortion, the surface is already patterned

FIN

Thanks for looking at the pictures, and bonus thanks for reading. This is a small beginning. Let me know what made sense and even better, what didn't make sense.